Table of Contents

Part of Series: Quantum Sovereignty & the New Cold War (Part 1 of 6)

This primer introduces the actors, stakes, and why “sovereignty” became the keyword. Later parts go deeper on the physics drivers, the geopolitical map, and the operational playbook.

Next: Physics at the Heart of the New Cold War · Index: Quantum Sovereignty Topic

On a crisp autumn morning in Hefei, China, a team of physicists cheered as their quantum computer performed a calculation once thought impossible. Halfway across the globe, engineers at an IBM lab in New York prepped a new quantum chip for a crucial test. In Washington, D.C., intelligence officials quietly accelerated efforts to secure military communications against quantum code-breaking. These scenes, disparate yet connected, reflect a single global narrative: the race for quantum sovereignty. In capitals from Beijing to Washington to Riyadh, leaders increasingly view mastery of quantum technology as key to future national power – a strategic asset as critical as oil or nuclear arms in decades past.

A New Technological Arms Race

The term quantum sovereignty has entered the geopolitical lexicon, capturing the idea that nations must control their own quantum technologies – from ultra-powerful quantum computers to unhackable quantum communications – or risk dependence on others. “The rapid advancement of quantum computing has ignited a fierce race for the next era of computing innovation globally,” noted a recent Middle East technology briefing. Indeed, echoes of past tech races are loud. A former U.S. Air Force scientist recently likened the U.S.–China competition in quantum to a new Cold War, a “quantum arms race” with parallels to the 20th-century struggle for nuclear supremacy.

But unlike the bipolar Cold War, today’s quantum race has many players. The United States and China are in the lead, pouring billions into research and jockeying for breakthroughs. The European Union, determined not to fall behind again as it did in the internet era, is investing heavily to secure “European quantum sovereignty.” Smaller nations and regional blocs – from India to the Gulf states – are also joining the fray, partnering with tech companies and allies to boost their quantum capabilities. The result is a complex global contest whose outcome could reshape economic and military balances. As one analyst put it, quantum computing’s “geopolitical weight” and its threat to current cybersecurity mean that not only the U.S. and China but also Europe, the U.K., India, Canada, Japan and others are “investing heavily in the technology… in the name of national security.”

(In this series, I use quantum sovereignty as a spectrum. At one extreme is hard quantum sovereignty (full-stack domestic control). For most countries and industries, the feasible target is sovereign optionality: staying integrated with global innovation while engineering the ability to pivot, verify, and swap dependencies when geopolitics turns them into liabilities.)

United States: Betting Big on Quantum

(Part 3 of the series covers national strategies systematically).

In the United States, quantum technology has moved from the lab to the highest levels of policy. Back in 2018, Congress passed the National Quantum Initiative Act, launching a coordinated federal program with an initial $1.2 billion to accelerate quantum research for economic and security ends. Since then, funding has only grown: lawmakers in 2024 pushed to expand this with another multi-billion dollar boost. “We cannot afford to fall behind” became a common refrain on Capitol Hill as quantum made the White House’s list of critical emerging technologies year after year.

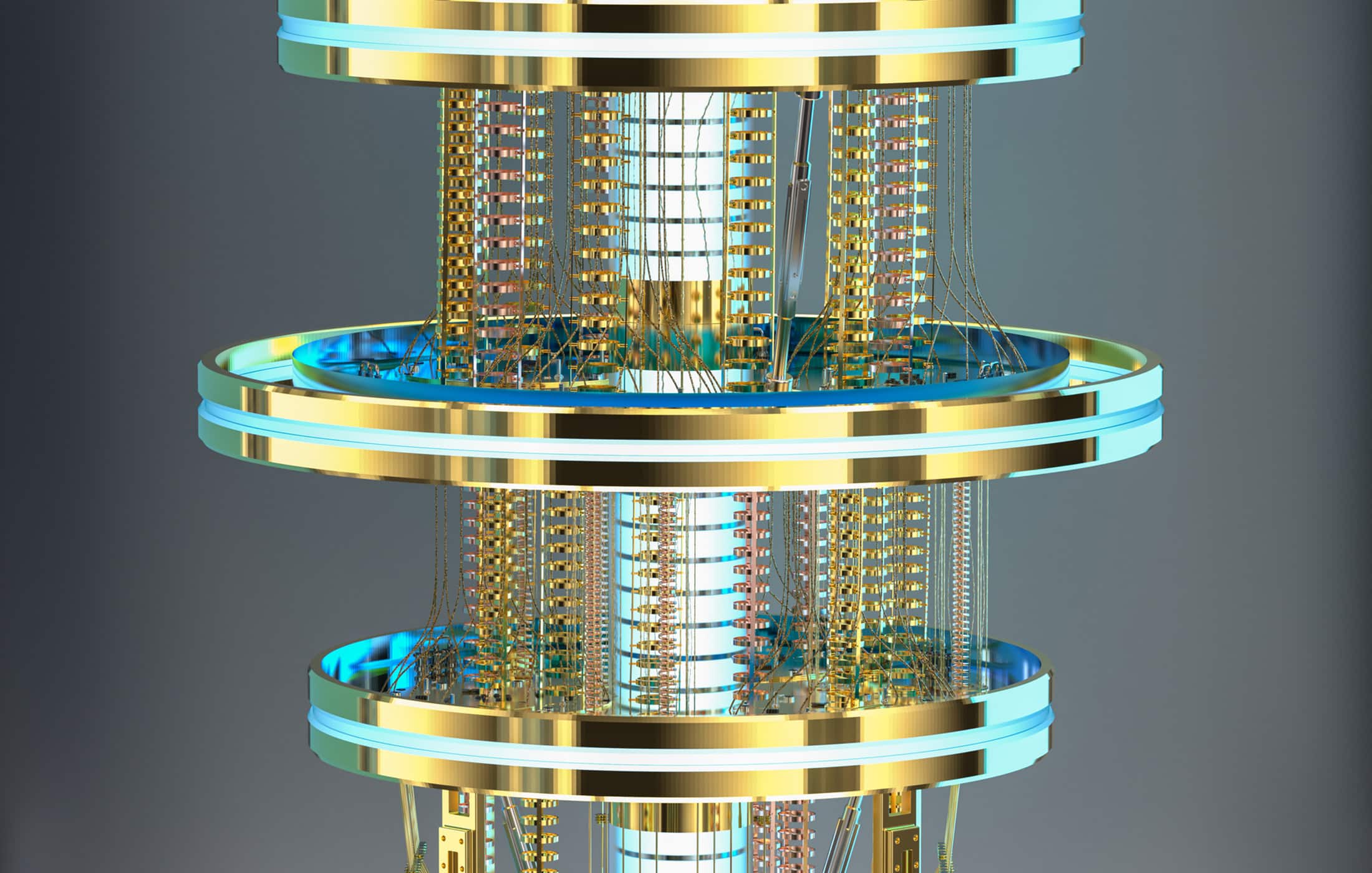

American tech companies and universities, often backed by federal grants and defense contracts, have led many early breakthroughs. Google’s 2019 claim of “quantum supremacy” – performing a calculation infeasible for a classical supercomputer – was a Sputnik-like moment that spurred wider urgency. IBM, meanwhile, has steadily rolled out quantum processors of increasing power, aiming for “utility-scale” quantum systems by the mid-2020s. Startups flourish with venture capital support, and the U.S. holds a commanding lead in quantum computing patents and talent.

Washington’s strategy isn’t just about building the most powerful quantum computer; it’s also about defending against quantum threats. U.S. agencies like NIST and the NSA have spearheaded development of post-quantum cryptography, new encryption standards resistant to quantum attacks. In 2022, the White House ordered federal systems to begin migrating to these quantum-proof algorithms, recognizing the risk that an adversary could one day decrypt sensitive data. “Harvest now, decrypt later” tactics are a real concern: encrypted communications stolen today might be unlocked in a decade or two by a sufficiently advanced quantum machine. American officials openly acknowledge this threat – and privately, U.S. intelligence is almost certainly stockpiling foreign intercepts in hopes of future decryption, just as they suspect others are hoarding American secrets.

On the offensive side, the U.S. military sees quantum computing as a potential ace up its sleeve. The Pentagon’s research arm DARPA and others are exploring quantum algorithms that could rapidly optimize logistics, model new materials for weapons, or break an enemy’s encryption in a flash. Stepping up the pace, the Department of Energy opened quantum research centers across national laboratories, and the CIA’s venture fund In-Q-Tel invested in quantum startups. By 2025, the United States was considered “still holding an edge” in quantum technology – but looking over its shoulder at China’s swift advances.

China’s Quantum Leap

(Part 3 of the series covers national strategies systematically).

China has embraced quantum technology with a fervor that meshes science, economic strategy, and nationalism. President Xi Jinping’s government identified quantum computing and quantum communication as “key critical infrastructure” for China’s future, placing it alongside AI and aerospace in a trio of strategic technologies for achieving national rejuvenation. Over the past decade, Beijing has spent lavishly: analysts estimate China is investing at least $10–15 billion in quantum efforts through state programs and tech giants – a level comparable to, if not greater than, U.S. and EU outlays. The result has been a series of headline-grabbing achievements.

In 2016, Chinese scientists led by Dr. Pan Jianwei launched the world’s first quantum communications satellite, nicknamed “Micius.” Soon after, they used it to beam entangled photons between Earth stations, demonstrating ultrasecure links over 1,200 km. By 2020, Pan’s team announced a satellite-to-ground quantum-encrypted video call, moving China closer to its goal of an “unhackable” quantum internet (to be precise: quantum-secure in principle – but implementation-security still matters). On the computing front, researchers at the University of Science and Technology of China built a photonic quantum computer (“Jiuzhang”) and a superconducting one (“Zuchongzhi”) that each claimed quantum computational advantage for specific tasks. Every success is trumpeted in state media and feeds a sense that China might leapfrog the West. Xi himself, at the 20th Party Congress in 2022, trumpeted the need to “strive to become the world’s primary center of science and innovation,” explicitly naming quantum technology as a field in which China must lead to shape the 21st-century global order.

Beyond raw research, China is rapidly building a quantum ecosystem. Government ministries coordinate with universities and companies to turn lab results into applications. A nationwide quantum communications backbone is under construction, with metropolitan fiber networks (Beijing, Shanghai and beyond) connected via satellite links – a distinct approach from the U.S., which is focusing more on quantum-proof classical encryption. Beijing’s quest is not just for technological bragging rights, but for independence: by developing its own quantum hardware, software, and even cryptographic standards (Part 6 of the series is the crypto/standards sovereignty deep dive), China aims to avoid reliance on Western tech. This desire for self-reliance became more pronounced after the U.S. imposed export controls on advanced chips. In fact, late 2024 saw Washington extend those export bans to quantum technologies, seeking to “curb Beijing’s progress” in the field. That move, reminiscent of Cold War-era tech embargoes, only reinforced China’s resolve to achieve quantum sovereignty – to innovate indigenously and dominate critical supply chains from quantum chips to sensors.

Militarily, the implications are profound. Chinese defense researchers openly discuss how quantum radar might one day detect stealth aircraft, nullifying a pillar of U.S. military superiority. Such claims are met with skepticism by Western experts – quantum radar remains unproven – but the mere fact that China is pushing the envelope worries strategists. The People’s Liberation Army is also studying quantum navigation systems that could guide submarines or missiles without GPS, and quantum clock technology to sync military networks with extreme precision. In espionage, China knows that a powerful quantum computer could decrypt an adversary’s secrets; Chinese intelligence is surely as keen as the NSA to win the code-breaking race. Little wonder that a “quantum arms race” is how many in Beijing and Washington describe the situation.

Yet there is also optimism in China’s scientific community that quantum tech will bolster the civilian economy – reinforcing the Communist Party’s narrative that high-tech development equals national rejuvenation. If China can own the patents and industries around quantum, it could reap enormous profits in finance, pharmaceuticals, materials science, and beyond, perhaps challenging Western tech hegemony. The stakes, as Chinese leaders see them, are nothing less than the future balance of global power.

Europe’s Quest for Autonomy

(Part 3 of the series covers national strategies systematically).

On a rainy afternoon in Brussels, policymakers gather to discuss an unusual topic for bureaucrats: Schrödinger’s cat. The thought experiment in quantum physics is invoked jovially, but the underlying issue is serious – Europe’s determination to avoid being the cat in someone else’s box, neither alive nor dead in the quantum era. The European Union has made technological sovereignty a rallying cry in recent years, and quantum technology is front and center. “Because the technology will profoundly disrupt business, government, and military networks, achieving quantum sovereignty is a critical task for the EU,” argued a Boston Consulting Group report. In 2018, the EU launched a ten-year, €1 billion Quantum Flagship project to fund research across member states. This public investment – larger than either the U.S. or China’s government outlays at the time – signaled Europe’s intent to catch up. And indeed, Europe excels in quantum research: from Dutch labs pioneering quantum networking to Austrian physicist Anton Zeilinger’s Nobel-winning experiments in entanglement, European scientists are among the leaders.

However, turning that research prowess into commercial and strategic gain is Europe’s challenge. The BCG study warned that while the EU leads in funding and talent on paper, it lacks coordination and risk capital – risking a repeat of the semiconductor fiasco decades ago when Europe fell behind. To counter this, the EU is considering a new “Quantum Act” to streamline efforts and pool resources, and initiatives like the European Quantum Industry Consortium (QuIC) are pushing for export controls and standards to protect Europe’s interests. Individual nations have announced their own programs: France unveiled a €1.8 billion plan, Germany earmarked €2 billion for quantum computing and even installed an IBM quantum system near Munich, while smaller states like the Netherlands and Finland punch above their weight with specialized centers. In March 2024, 21 EU countries agreed to make Europe the “Quantum Valley” of the world, signing a declaration to boost collaboration and skills training.

Strategically, the EU’s drive for quantum tech is partly about reducing reliance on U.S. and Chinese innovations. European leaders have watched the U.S.–China tech rivalry warily; they know a world split into American and Chinese quantum ecosystems could leave Europe in a junior role, dependent on foreign hardware or cloud access. To avoid this fate, Europe is doubling down on building an autonomous quantum ecosystem – from homegrown startups to its own quantum-secure communications network (the EuroQCI project) spanning the continent.

Even so, transatlantic cooperation persists. European and American researchers continue to collaborate, and NATO has launched quantum initiatives recognizing the technology’s defense importance. But if push comes to shove, Brussels wants Europe to stand on its own qubits. In an era when control over tech equals control over destiny, the EU is determined that the next generation of encryption, computing, and communications won’t rely solely on Silicon Valley or Shenzhen.

Quantum Ambitions in the Gulf

(Part 3 of the series covers national strategies systematically).

Not all quantum powerhouses are superpowers or giants. In the Middle East, a perhaps unexpected player is emerging: the nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Places like the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar – better known for oil wealth – are investing in quantum technology as part of a broader bid to diversify economies and gain technological clout. Saudi Arabia, for instance, has woven quantum into its Vision 2030 blueprint for a modern, knowledge-based economy. The kingdom’s researchers and officials, with support from the highest levels, are drafting a national quantum strategy that spans computing, communications, and sensing. A recent report by a Saudi innovation center stressed the need for developing “critical quantum technologies, software, hardware and supply chain components” domestically to ensure future sovereignty. In other words, Saudi Arabia doesn’t just want to buy a quantum computer someday – it wants to build one, or at least cultivate the talent and infrastructure to be a serious player.

The UAE is moving particularly fast. In 2021 Abu Dhabi founded a Quantum Research Center, and by 2024 it had struck a landmark deal with U.S.-based IonQ to secure access to one of the world’s most advanced quantum computers. This placed the UAE among just a handful of users of such cutting-edge systems. “Our continued work with IonQ enables us to stay at the forefront of quantum research and further the UAE’s position as a leading technology and innovation hub,” said Professor Leandro Aolita of the Quantum Research Center. In practical terms, Emirati scientists can now run experiments on IonQ’s machine to explore applications in finance, chemistry, and materials – leapfrogging the need to build their own hardware for now. The Gulf’s largest state, Saudi Arabia, is likewise establishing quantum labs at its universities and has hinted at partnerships with international tech firms. Meanwhile, Qatar signaled its intentions by co-investing $100+ million in a European quantum computing startup, and by setting up a Qatar Center for Quantum Computing with foreign advisors. Even smaller Kuwait and Oman have begun hosting workshops on quantum tech for students, determined not to be left out of the future.

For the Gulf states, quantum technology serves multiple strategic goals. Economically, it aligns with plans to create high-tech industries and jobs for a post-petroleum era. Owning quantum capabilities could attract investment and give local companies an edge in fields like cryptography and optimization for logistics or energy management. Geopolitically, there’s prestige in being among the vanguard – a reason the UAE touts its quantum deals in press releases. And there’s a security dimension: Gulf governments face intense cyber threats in a volatile region, so being early adopters of quantum-secure communications or post-quantum encryption is a national insurance policy. It’s telling that “the Middle East, including UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, is part of this fierce race” for quantum tech. These countries are leveraging their wealth to buy into the game early, effectively trading petro-dollars for qubits.

One fascinating aspect is how the GCC states navigate between the U.S. and China. Traditionally aligned with the West, they are nonetheless open to cooperation with all sides in tech. For now, American and European partnerships (like the UAE-IonQ deal or Qatar funding a French startup) dominate, and the U.S. is happy to have its Gulf allies on the cutting edge – as long as China isn’t their vendor. Indeed, the new U.S. export controls on quantum tech likely reinforce the Gulf’s tendency to source from the West. Yet the Gulf states also maintain ties with China (which is investing in Middle East tech ventures), so down the line they could serve as bridges or even brokers in a quantum-divided world. In any case, the GCC’s entry into quantum ambition underscores that quantum sovereignty isn’t just a concern for superpowers – even mid-sized nations see it as vital to “diversify… economy and establish… a global hub for the quantum economy”.

The Stakes: Security, Economy, and Military Power

Why does quantum technology inspire such urgency? The answer lies in its disruptive potential across security, economics, and military affairs. At heart, a quantum computer exploits the counterintuitive properties of subatomic particles to process information in fundamentally new ways. Where classical computers calculate with bits (either 0 or 1 at any time), quantum computers use qubits that can exist in superposition – essentially 0 and 1 at the same time – and become entangled with one another to act in concert at a distance. The upshot is an large speedups for specific problem classes: a well-developed quantum computer could perform in seconds tasks that would take today’s fastest supercomputers thousands of years. That prospect underpins both the hopes and fears fueling this global race.

Cybersecurity is the most immediate concern. Modern encryption protocols (securing everything from military secrets to online banking) rely on mathematical problems so hard that classical computers can’t crack them in reasonable time – for example, factoring the large numbers underpinning RSA encryption. Quantum algorithms like Shor’s algorithm threaten to undermine these defenses by drastically accelerating those hard computations. Whichever nation first builds a large, stable quantum computer could potentially unlock all encrypted data it intercepts, past and present. Intelligence agencies are keenly aware of this “Q-day” scenario. As noted, they are already preparing mitigations: the U.S. leading with post-quantum cryptography standards (Part 6 of the series is the crypto/standards sovereignty deep dive), and China aiming to leap ahead with quantum-encrypted networks that render classical hacking moot. A successful quantum code-breaker would be a strategic super-weapon; conversely, a secure quantum communication network could shield a country’s command-and-control from any eavesdropping. This is why quantum keys and algorithms are now seen as strategic assets, and why NATO allies and others are rushing to upgrade cryptography. It’s also why data is being harvested now to decrypt later. A quantum-empowered adversary could, in theory, expose another nation’s state secrets, diplomatic cables, even citizens’ personal data – a nightmare for security and privacy.

The economic implications are equally massive. Quantum computers promise to revolutionize industries by solving complex optimization and simulation problems. In finance, they could optimize global investment portfolios or risk models far better than classical algorithms, yielding huge profits to those with access. In pharmaceuticals and materials science, quantum machines could accurately simulate molecular interactions, potentially discovering new drugs or high-performance materials in a fraction of the time – advantages worth billions. Boston Consulting Group estimates that quantum computing could create $450–$850 billion of value globally in the next 15–30 years. The race to capture this value is on. Governments see economic competitiveness on the line: if one country’s companies harness quantum first, they might dominate next-generation industries, much as early internet adopters reaped outsized gains. This is one reason the EU is keen not to depend on American or Chinese quantum cloud services – that could mean a permanent disadvantage for European firms. We might soon see a “quantum divide” where countries with top quantum infrastructure attract talent and investment, while others fall behind and must pay a premium to use foreign quantum services. That divide could exacerbate global inequality and reshape supply chains (imagine critical drug formulas or advanced materials known only to the quantum “haves”). Major powers are also eyeing the job creation and intellectual property that come with leading in quantum tech. Patents in quantum algorithms or error-correction techniques could be goldmines. No one wants to be solely a buyer in the future quantum economy; everyone wants a piece of the IP and the high-value jobs that come with quantum industries.

Then there’s the military dimension. Quantum technology is often compared to the advent of nuclear weapons in terms of its potentially game-changing impact. A powerful quantum computer could break enemy codes and cripple their secure communications – essentially the modern equivalent of cracking the Enigma in World War II, but on steroids. Quantum-enabled sensors might detect submarines in the ocean by sensing minute gravitational or magnetic anomalies, stripping away the stealth that navies have relied on. Ultra-precise quantum clocks and inertial sensors could give missiles and aircraft perfect navigation even when GPS satellites (often vulnerable to jamming) are knocked out. And as mentioned, the theoretical quantum radar that could spot today’s stealth fighters and bombers is a military planner’s dream (or adversary’s nightmare). While such applications remain experimental, the first nation to deploy them would gain a serious strategic edge. This fuels a quieter part of the quantum race: defense ministries funding classified research. The U.S. Department of Defense, for example, has quantum programs for secure battlefield communications and sensing. China’s military is deeply involved in its national quantum labs. Even smaller countries like Israel and Australia have defense-driven quantum research (e.g. quantum navigation to back up GPS). A quantum advantage in warfare – however small initially – could tip scenarios, much like superior radar or code-breaking did in the past. Thus, generals and admirals are paying attention, and budgets for “quantum defense” are growing.

Finally, quantum tech promises to boost infrastructure resilience at home. Quantum-enhanced sensors could improve the electric grid by detecting fluctuations instantly, or monitor bridges and pipelines with unprecedented sensitivity to prevent failures. Quantum random number generators can strengthen cybersecurity for critical infrastructure by providing truly uncrackable encryption keys. Quantum computers might also optimize traffic flow in smart cities or supply chains for critical goods. Governments see these potential benefits for domestic stability and innovation. For instance, an oil-exporting country might use quantum optimization to enhance refinery efficiency or logistics – small percentage gains that translate to big dollars. Or a country worried about cyber-physical attacks on power plants might deploy quantum communications to secure those facilities. In short, quantum tech could undergird the next generation of critical infrastructure, making it smarter and more secure – advantages no nation wants to cede to a rival.

A Coming Quantum Divide?

(Part 3 of the series expands the ‘gap’ dynamics and policy responses).

All these factors point to an emerging stratification of the world into quantum haves and have-nots – what some call the quantum divide. We saw a similar pattern with the digital divide, where early adopters of the internet and computing surged ahead economically and militarily. With quantum, that gap could be even sharper. A few top-tier nations (or alliances) might achieve self-sufficiency in quantum computing and encryption, while others are forced to rely on purchasing services or hardware from the leaders. If those leaders are benevolent, perhaps they’d offer cloud access or license out breakthroughs; if they’re not, latecomers could find themselves shut out of critical knowledge or paying steep geopolitical prices for access.

The geopolitical blocs are already taking shape. The U.S. and its close allies – including the U.K., Canada, Australia (all of whom have notable quantum programs) – are increasingly coordinating on technology protection. There’s talk of an alliance to ensure trusted supply chains for quantum components, much as the West has done for semiconductor chips. Export controls like the U.S. ones targeting China aim to keep quantum advantage within a friendly circle. China, on the other hand, is building its own sphere: collaborating with Russia (which, despite economic struggles, maintains a solid base of quantum physics talent) and courting partners in Asia and the developing world. If Beijing succeeds in creating a quantum communications network linking friendly capitals (say, connecting China with the Middle East, Africa, or South America via secure satellites), it could form a quantum-secure bloc resistant to Western surveillance.

Even Europe faces choices: it wants strategic autonomy but remains tied to the U.S. through NATO and trade. Some in Europe worry about being caught between an American quantum cloud and a Chinese quantum network. This has led to calls for European-led infrastructure – for example, a Euro Quantum Internet linking EU governments and militaries with homegrown QKD (quantum key distribution) systems. Such moves could in turn spur the U.S. and Asia-Pacific allies (Japan, South Korea, etc.) to integrate their quantum defenses, lest Europe drift into its own camp. We could witness a future where data from London to Sydney travels over one quantum-secure network, while data from Beijing to Tehran travels over another, with limited interconnectivity. A fragmentation of the global internet into quantum-secured zones might occur, mirroring broader geopolitical rifts.

The developing countries risk being left behind entirely. Just as many skipped the industrial revolution and only caught up partially in the digital age, quantum could leave gaps. There’s concern that without some knowledge transfer or affordable access, regions like Africa or Latin America may depend wholly on foreign quantum services, effectively surrendering a bit of their sovereignty. Recognizing this, some international bodies and companies talk about “democratizing” quantum tech – for instance, offering cloud-based quantum computing access even to those without their own hardware. But if geopolitical tensions worsen, such sharing might be limited to allies. A country that falls out with a quantum superpower could find its access cut off. In a more dystopian scenario, imagine an economic sanction regime where a rogue state is denied not just conventional tech but also any quantum tools, leaving it extremely vulnerable in encryption and unable to benefit from quantum-accelerated progress in various fields.

In positive terms, one could also see new alliances forming: maybe a pan-Arab or pan-Islamic quantum initiative, or South-South cooperation where countries pool resources to collectively gain quantum capabilities. The GCC’s early moves might inspire neighbors – perhaps a Turkey or an Egypt – to collaborate regionally. Likewise, smaller European states could team up with, say, Israel or Singapore, which are quantum innovation hotbeds, to avoid dependence on the big powers. “No sovereignty for Europe without shared capacity,” as one European think-tank put it , and the same logic may drive other groups. Quantum technology might thus redraw alliance maps, creating new tech-centric partnerships that cut across traditional lines.

The Next Five to Ten Years: Quantum Futures

(The following vignettes are illustrative scenarios, not predictions.)

It is the year 2030. An autonomous electric ship carrying thousands of tons of cargo plots its course across the Pacific. Unbeknownst to its crew, a quantum computer half a world away has just cracked the encryption on its navigation system. Elsewhere, a clinic in Berlin synthesizes a revolutionary new drug – its molecular design optimized by a quantum machine in minutes – while a stock trading algorithm in New York, powered by quantum acceleration, executes market plays with uncanny precision. In the South China Sea, a once-invisible submarine finds itself tracked by a strange new radar, its stealth pierced by quantum-enhanced sensing. And in a data center buried under Swiss Alps, a desperate engineer watches as hackers effortlessly bypass what was once thought an unbreakable code. These hypothetical vignettes illustrate the divergent futures quantum technology could bring in 5–10 years – some hopeful, some harrowing.

One scenario is a world where quantum breakthroughs arrive faster than expected, tilting the balance decisively in favor of one bloc. Perhaps by 2030, China announces a 1,000-qubit fault-tolerant quantum computer that can break common encryption in hours. Q-day is here. The U.S. scrambles to deploy post-quantum encryption everywhere, but not before some secrets slip out. China, having prepared with its quantum networks, secures its communications. Global markets tremble as trust in financial encryption wavers. Sensing an opportunity, Beijing offers its quantum-secure communication services to friendly nations – and even to companies – at a price, creating a new sphere of influence. The West faces a choice: accept Chinese quantum tech in global banking transactions (with all the potential backdoors that entails), or rapidly build an alternative system. This future would feel like “Sputnik” redux, potentially triggering a level of tech tension not seen since the 1960s. It could even spark discussions of arms control for quantum computing – an international treaty to limit use of quantum code-breaking, akin to nuclear arms treaties. Whether such an agreement could be verified (how to prove someone isn’t running a secret quantum code-breaker?) is an open question.

Another scenario is more incremental and cooperative. Quantum progress proves harder than hype suggested – a common refrain among cautious physicists. By 2030, quantum computers exist with a few thousand qubits, but they require error-correction overhead that makes them only marginally useful beyond niche tasks. No encryption is fully broken yet, giving the world time to adapt. Nations focus on quantum-proofing before the storm. Through bodies like the UN’s ITU or academic consortia, they share knowledge on post-quantum cryptography standards. An international agreement bans the use of intercepted data after Q-day, similar to how some nations pledged no first use of cyberattacks. Rival powers might even establish a hotline to manage quantum incidents (imagine a sudden collapse of a major cryptosystem – immediate transparency could prevent panic or misblame). In this scenario, quantum tech still changes the world – new drugs, materials, AI advances flow gradually – but it does so more evenly. Cloud-based quantum services are widely available, so even countries without their own hardware benefit from the advances (much as countries without big supercomputers today still benefit via cloud computing). The quantum divide exists but is narrowed by conscious effort to include more players. This would be a relatively benign outcome where quantum tech becomes a new global utility akin to satellite GPS – crucial, but accessible.

Yet another scenario lies in between: a fragmented future where two or three quantum ecosystems dominate. By the late 2020s, the U.S. and its allies develop a robust network of quantum data centers and quantum-encrypted communication lines – Quantum Internet 1.0. China and partners have their own. They do not interoperate much, due to lack of trust and different standards. Global tech firms choose sides or attempt dual compatibility. International finance might even split, with separate quantum-secured banking networks for different blocs. Countries in the middle, like those in the Non-Aligned Movement of old, attempt to stay neutral and possibly form a third minor ecosystem (perhaps using European tech as a base, since the EU might position itself as an “alternative” provider not controlled by either Washington or Beijing). In this world, if a country switches political alliances, it might have to “re-key” all its communications to a new quantum system – a costly and telling move. Espionage goes on, but it’s back to old-school human spying or malware, since tapping quantum links is futile. Military tensions might stabilize on the cyber front because each side knows the other’s networks are shielded – or they might worsen as states feel emboldened by their secure lines, leading to miscalculation. This fragmented outcome is plausible given current trajectories: the U.S. actively coordinating with allies, China with its own vision, and Europe asserting independence.

Importantly, in all futures, classical computing doesn’t disappear. Just as airplanes didn’t make ships obsolete overnight, quantum computers will augment rather than replace classical ones for many tasks. But who harnesses quantum best will matter enormously. The next 5–10 years are pivotal. It’s a period akin to the early space race – lots of experimentation, some dazzling firsts (a quantum computer solving a chemistry problem no classic computer can, or a continent-spanning quantum-encrypted video call), and possibly a few crises (a major encryption break, or a scandal where someone’s quantum device was used for financial manipulation). Governments and international institutions are just beginning to grapple with questions of quantum governance: Who sets the rules for a quantum internet? How do we verify quantum arms control? Can we establish norms, like agreeing not to target each other’s quantum infrastructure in conflict? These discussions lag behind the technology.

One certainty is that quantum innovation will continue accelerating due to the very competition it has spurred. In 2025, over a dozen countries had national quantum programs; by 2030 that number could double, with even developing nations earmarking funds to develop quantum expertise. Global spending on quantum R&D – public and private – is climbing steeply each year. This virtuous (or vicious) cycle means new talent is entering the field worldwide. Some experts foresee a “quantum Moore’s Law” of sorts for the coming decade, where qubit counts and coherence times improve exponentially. If that holds true, by the early 2030s we might routinely solve problems that are impossible today. The world could benefit enormously – from life-saving medicines to climate modeling breakthroughs – or it could stumble into a security nightmare if our cryptographic foundations crumble too soon. Likely, we will see some of both: progress and disruption, cooperation and rivalry.

Epilogue

Late one night in 2032, a small quantum computer in a Nairobi tech hub finally stabilizes 100 qubits, a milestone for Africa’s budding quantum community. They celebrate, knowing they are now part of this new chapter of technology – not leading, but not absent either. In Silicon Valley, an engineer checks the results of a complex quantum algorithm optimizing the electric grid, keeping blackouts at bay during a heatwave. In Moscow, analysts puzzle over why their decades of intercepted NSA communications remain indecipherable, as post-quantum encryption foils their code-breakers. And on the Moon – humanity’s next frontier – astronauts from multiple nations set up a communication relay secured by quantum keys, ensuring that as we push forward, we also bring along the best protections science can offer.

The race for quantum sovereignty is not a winner-takes-all sprint; it’s a marathon with many runners and no clear finish line. Along the way, nations will experience bursts of exhilaration at breakthroughs and moments of dread at the implications. In the end, mastering quantum technology will require not just qubits and algorithms, but wisdom in how we wield this double-edged sword. The world is entering the quantum age – entangled, uncertain, yet full of possibility – and the choices made now will resonate for decades to come, echoing across entwined fibers and through the quiet click of superconducting circuits in the cold midnight of a quantum computer lab.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.