Enterprise PQC Migration: New Study Predicts 5–15+ Year Timelines

Table of Contents

27 Dec 2025 – A new peer-reviewed study titled “Enterprise Migration to Post-Quantum Cryptography: Timeline Analysis and Strategic Frameworks” by independent researcher Robert Campbell has been published in the open-access journal Computers (MDPI).

This paper provides one of the most comprehensive analyses to date of how long it will take enterprises to fully migrate their cryptographic systems to post-quantum cryptography (PQC). The findings are striking, and very much aligned with what I’ve been saying for years: even under optimistic assumptions, small enterprises may need 5-7 years to complete the transition, medium enterprises 8-12 years, and large enterprises 12-15+ years.

These timelines far exceed many early expectations and underscore that the PQC migration is not a simple software update but a complex, multi-year transformation. The study situates these estimates in context – tying the migration challenge to broader strategic issues like Zero Trust architecture, crypto-agility, and the looming threat of quantum-enabled adversaries – and offers a sobering call to action for organizations to start preparing now.

Projected Timelines and Key Findings

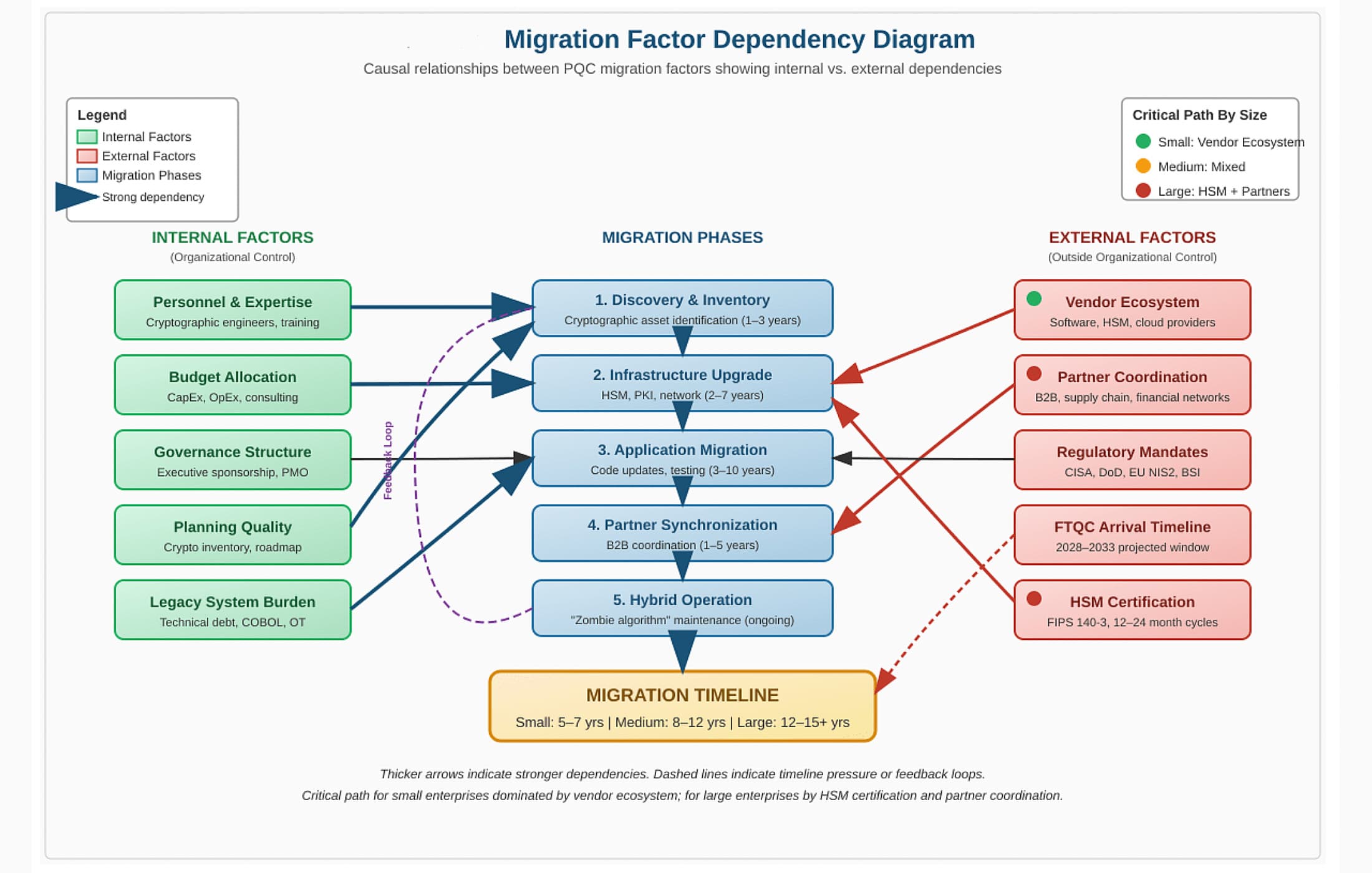

Campbell’s analysis, which draws on expert input and historical precedents, concludes that a small enterprise (e.g. a firm with under 500 employees) will likely need on the order of 5–7 years to become fully quantum-safe. A medium enterprise (hundreds to a few thousand employees, with hybrid IT environments) might require 8–12 years, and a large enterprise (global firms with thousands of applications and extensive legacy systems) could take 12–15+ years to complete the migration. These are baseline estimates under normal conditions; the paper notes that pessimistic scenarios could stretch even longer. Such timelines are well beyond the “couple of years” optimism that some executives may have hoped for. In fact, the study explicitly argues that realistic timelines “extend well beyond initial optimistic estimates”, emphasizing that PQC migration is “not a siloed technical upgrade but a global synchronization exercise” involving many external dependencies. In other words, this isn’t just about updating an algorithm in your software stack – it’s about coordinating an entire ecosystem of hardware, software, vendors, and partner organizations in unison.

Why PQC Migration Is So Complex: A Multi-Dimensional Challenge

Why do these migrations take so long? The research underscores that transitioning to post-quantum cryptography is orders of magnitude more complex than past crypto upgrades (such as the move from SHA-1 to SHA-2 or the TLS 1.3 rollout). Multiple dimensions of complexity all interlock to slow down progress. Key factors include:

- Vendor and Ecosystem Dependencies: No enterprise can go quantum-safe alone. Organizations depend on hardware and software vendors, cloud providers, and open-source libraries to deliver PQC-capable products. If a critical vendor only adds PQC support 2–3 years after NIST standards are finalized, that lag directly pushes out the customer’s migration by those years (on top of internal rollout time). Companies must engage vendors early and pressure them for roadmaps, but ultimately they are beholden to external product cycles. This supply-chain dependency means part of the timeline is outside a single enterprise’s control. (As one earlier analysis on PostQuantum.com noted, external third-party readiness should be tracked in the risk register and factored into migration plans.)

- Infrastructure Upgrades and HSM Replacement: PQC algorithms introduce new technical requirements – notably larger key sizes and signatures, and different performance profiles – that often cannot be handled by legacy hardware and networks. For example, existing hardware security modules (HSMs), smart cards, and network middleboxes may need firmware updates or complete replacement to support lattice-based encryption and new signature schemes. Upgrading critical infrastructure (data center appliances, VPNs, IoT devices, etc.) is a time-consuming process, often tied to hardware refresh cycles. The study indicates that infrastructure upgrade phases alone can take several years, especially in environments with extensive hardware dependencies.

- Cryptographic Inventory and Discovery: A foundational but labor-intensive step is discovering where all the vulnerable cryptography lives in an enterprise. Many organizations do not even know all the places RSA or ECC are used in their systems. The paper reiterates that building a cryptographic asset inventory is an essential early phase – identifying every certificate, protocol, library, and device that relies on pre-quantum algorithms. This discovery can take 1-3 years even with automated tools, because cryptography is everywhere (embedded in applications, firmware, third-party services) and often poorly documented. As we’ve discussed previously on PostQuantum.com, you can’t fix what you can’t find – and crypto discovery is now recognized as a critical prerequisite for PQC readiness.

- Hybrid Cryptography Deployment: During the transition, many systems will adopt hybrid cryptographic schemes – combining classical RSA/ECC and PQC algorithms – to maintain compatibility and defense-in-depth. The study notes that hybrid modes are a necessary stopgap but come at the cost of doubling cryptographic operations in many cases, further increasing message sizes and latency. Managing these hybrid deployments (and later phasing out the legacy algorithms) adds operational complexity. Ensuring that all parties agree on protocol specifics (e.g. which hybrid modes or parameter sets to use) requires coordination through standards bodies and industry groups to avoid interoperability failures.

- Zero Trust Architecture Interdependencies: Interestingly, the paper highlights that PQC migration is “deeply intertwined with Zero Trust Architecture” initiatives. Many organizations are simultaneously working on Zero Trust (which involves pervasive encryption and authentication at every layer), and you cannot fully achieve Zero Trust if your cryptographic primitives are not quantum-safe. In practice, this means every pillar of Zero Trust – identity, network segmentation, device trust, etc. – eventually depends on quantum-resistant cryptography. As the study observes, an organization cannot complete its Zero Trust rollout until all authentication factors and channels are quantum-resistant. Conversely, doing both Zero Trust and PQC migration together strains resources and can extend the timeline for each. Careful sequencing and interim risk trade-offs are required so that security isn’t compromised during the transition period.

- Personnel and Expertise Bottlenecks: Upgrading to PQC isn’t just a tech deployment problem – it’s a people problem. There is a global shortage of cryptography experts familiar with post-quantum algorithms, and specialized training is required for engineers, developers, and security staff to properly implement and operate new crypto systems. The study warns that personnel constraints will extend migration timelines by years in many cases. Enterprises can’t simply hire armies of PQC experts because the talent pool is limited; instead they must train existing teams and phase the work in manageable waves. External consultants are also in high demand – vendors, government agencies and enterprises are all competing for the same scarce expertise. This “consultant bottleneck” means mid-sized firms might end up waiting in line for vendor toolkits or external help, directly impacting that 8–12 year timeline for medium enterprises.

- Inter-Enterprise Coordination: Perhaps one of the most challenging aspects is the need for broad coordination across organizations. Modern businesses are highly interconnected – they exchange data and authenticate with suppliers, clients, payment networks, cloud services, regulators, and more. If your systems become quantum-safe but your key partners’ systems do not, you may be forced to maintain insecure legacy connections or run “dual stack” crypto (classical and PQC) indefinitely. Sectors like banking and healthcare involve hundreds or thousands of organizations that must all migrate in sync to truly retire vulnerable algorithms. The paper gives examples such as the global financial networks (SWIFT, payment card networks, etc.), where a single laggard institution can hold back everyone else and force prolonged hybrid operation. Achieving industry-wide coordination adds an entirely new layer of complexity that simply didn’t exist in earlier cryptographic transitions.

In short, the timeline is long because everything has to change, and it has to change in a coordinated fashion. As Campbell writes, PQC migration “requires coordination across enterprises, vendors, regulators, and communication partners spanning multiple jurisdictions” – a far cry from just applying a patch on your own systems. The new algorithms impact performance and interoperability in fundamental ways, touching hardware, software, and human processes. The multi-dimensional hurdles of technical debt, supply chain dependencies, organizational change management, and regulatory compliance all pile on. This insight aligns with warnings we’ve been raising on PostQuantum.com for some time: quantum readiness is a strategic, enterprise-wide challenge, not just a cryptography update. There is no “one-click fix.”

Collision with the Quantum Clock: Migration vs. Qubit Timelines

One of the most urgent implications of these findings comes from overlaying the migration timelines against forecasts for when quantum computers will be capable of cracking current encryption. Various industry roadmaps and experts predict that a cryptographically relevant quantum computer (CRQC) – one able to run Shor’s algorithm to break RSA/ECC – could be ready as early as 2028–2033. This range is much sooner than many previously assumed, due to rapid advances in quantum hardware (e.g. IBM’s 1000+ qubit prototypes and projected 100,000+ qubit systems by 2033, IonQ’s plans for 2028, Google’s breakthroughs in error correction).

Now consider a large enterprise that begins its PQC migration in 2025 and takes, say, 13 years to finish. That puts completion around 2038. But a capable quantum adversary might arrive by 2030. The sobering result, as the paper points out, is a multi-year window of vulnerability: a period of perhaps 3-5 years (or more) during which some critical fraction of the enterprise’s infrastructure is still using broken cryptography, while quantum attackers are operational. In Campbell’s words, “If large enterprises require 12-15 years for complete PQC migration, and FTQC arrives in 2028-2030, enterprises beginning migration in 2025 face a 3-5-year window where significant portions of their infrastructure remain vulnerable”. This gap is essentially a race condition between defense and offense, and right now, defense is slated to finish second.

The study quantifies this as a risk deficit – a span of time during which an organization’s security posture is known to be insufficient against the quantum threat. Crucially, for data that needs to remain confidential well beyond 2030 (think: state secrets, health records, long-term intellectual property, etc.), waiting until 2035 or later to secure it is effectively too late. Any such data not already protected by PQC today must be assumed at risk, because an adversary could steal it now and decrypt it as soon as their quantum capabilities come online. In risk management terms, the arrival of quantum cracking capability is a ticking clock, and every month of delay in migration increases the chance that some sensitive data will “age into” vulnerability.

“Store Now, Decrypt Later”: The Immediate Threat

The lag between enterprise migration and quantum computer development wouldn’t be as alarming if it weren’t for the Store Now, Decrypt Later (SNDL) threat model. This scenario, highlighted prominently in the paper, is not theoretical at all – it’s happening today. Adversaries (state-sponsored groups in particular) are harvesting encrypted data now, on the assumption that it can be decrypted in the future once they have a powerful quantum computer. This strategy turns the timing issue into an urgent present-day risk. Unlike other cybersecurity threats that materialize gradually, SNDL creates a binary “zero day” for all your historical data: the moment a quantum computer capable of breaking encryption emerges, every piece of encrypted information previously captured by attackers suddenly becomes readable.

This is why experts keep stressing that for certain categories of data, the quantum threat is already here. Campbell’s paper reinforces this point by enumerating the types of information at risk right now: any data with confidentiality requirements extending beyond the next few years – e.g. long-lived personal data under GDPR/CCPA, long-term financial contracts, sensitive R&D data, and of course government classified information – must be considered exposed under the SNDL threat. If an enterprise’s PQC migration won’t be finished until the 2030s, that enterprise effectively needs to protect those high-value long-term assets today using interim solutions (such as hybrid encryption or store-encrypt-now-with-PQC for the most critical data). The paper drives home that SNDL makes the quantum timeline debate “moot” for organizations with long-lived data – regardless of whether the first CRQC arrives in 2028 or 2035, the prudent approach is to act as if it could be 2028.

In practice, this means starting the transition immediately for systems that handle sensitive data, because every year of delay is a year that adversaries are quietly stockpiling your still-encrypted secrets.

Notably, this real-world urgency is echoed by government security agencies. The study cites guidance from CISA, NSA, and NIST that explicitly recommends beginning PQC migration now, well before any quantum computer is operational. The rationale is exactly SNDL – waiting for absolute certainty about Q-Day (the day a quantum break becomes possible) is waiting too long. By the time we have confirmation a quantum computer is ready, anything not already protected is effectively compromised. This urgency underpins many of the strategic recommendations both in the paper and from regulators: prioritize the “low-hanging fruit” of quantum-safe encryption for the most sensitive data, implement hybrid solutions as an interim measure, and bake quantum resistance into new systems being deployed going forward.

Crypto-Agility, Strategic Planning, and Policy: Earlier Insights Reaffirmed

Importantly, the paper doesn’t just quantify the problem – it also reinforces a number of themes that PostQuantum.com and others have been advocating in recent years. The conclusions align with a broader narrative about crypto-agility, proactive planning, and even regulatory impetus in the move to a quantum-safe future.

One recurring theme is the need for cryptographic agility. The new paper explicitly ties PQC migration to building long-term crypto-agility, noting that this transition “is deeply intertwined with … long-term crypto-agility”. In essence, organizations must be able to swap out cryptographic components seamlessly as threats evolve. We have previously emphasized that PQC is likely not the last crypto transition we’ll see – whether due to new cryptanalytic advances or future quantum improvements, we may need to upgrade algorithms again in the coming decades. Campbell’s study underlines this by calling for architectures that can accommodate algorithm changes (e.g. support for hybrid modes and dynamic protocol negotiation as outlined in his strategic frameworks). Embracing crypto-agility means treating cryptography as a flexible, pluggable component in systems – a cultural shift from the old “set it and forget it” mentality. In practice, this might involve deploying PQC algorithms in a way that you can roll them out gradually and fall back to alternatives if needed, and ensuring that policy engines, identity systems, and applications can handle algorithm agility. The new research validates that without such agility, enterprises will struggle not only with this migration but with the next one.

Another major thread is strategic planning and program governance. The magnitude of a 5-15 year effort means that organizations must approach PQC migration as a formal program, not an ad-hoc project. The study points to the necessity of executive sponsorship, dedicated budgets, and cross-department coordination – effectively treating this like a digital transformation initiative. This is very much in line with advice we’ve given: for example, boards and CISOs should view quantum risk mitigation as a business issue requiring a decade-long roadmap, not just an IT task. The new paper’s analysis of migration phases (discovery, infrastructure upgrades, application migration, etc.) provides a framework for such a roadmap. It also notes that planning quality itself can swing timelines by several years. Organizations that take the time to do thorough cryptographic inventories, risk prioritization, and pilot testing can avoid false starts and wasted effort. By contrast, those that procrastinate or lack clear ownership may hit unexpected roadblocks (like hidden legacy systems using obsolete crypto) that force reactive extensions to their schedule. We’ve repeatedly stressed the importance of starting with a clear-eyed assessment – essentially a “Quantum Readiness” evaluation – to scope the problem and set priorities. Now we have data-backed projections that show the cost of poor planning is measured in years.

Finally, there’s the aspect of regulatory response and external pressure. Just as regulations eventually forced action in past crypto transitions (think of browser vendors setting deadlines for SHA-1 deprecation, or compliance rules driving TLS adoption), we are seeing the early stages of quantum-related mandates. Campbell’s paper touches on differing regulatory timelines across jurisdictions – for instance, the U.S. federal government has its own PQC deadlines, the EU is introducing requirements through its NIS2 directive, etc., all of which can add complexity for multinationals. But regulation can also be a catalyst: national security agencies and industry groups are increasingly issuing guidelines and even binding orders to compel organizations to start the PQC transition.

In conclusion, the publication is a timely and important milestone for the post-quantum security community. It translates the abstract concept of “we need to act before quantum computers arrive” into concrete timelines, risk models, and strategic steps. The takeaway is clear – the quantum threat may be approaching faster than the ability of enterprises to respond, so the only solution is to start the marathon now and run it with a strategic, well-coordinated plan.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.