Quantum of Flapdoodle: A Guide to Quantum Hype and Scams

Table of Contents

Introduction

Quantum mechanics, the fundamental theory of physics describing the universe at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles, is famously counterintuitive. Its principles – superposition, entanglement, uncertainty – defy the logic of our everyday experience. This inherent “weirdness,” combined with its profound technological promise, has created a fertile ground for misinformation. The physicist Murray Gell-Mann, a Nobel laureate, coined the term “quantum flapdoodle” to describe the rampant misuse and misapplication of quantum physics to unrelated topics. Today, this flapdoodle has evolved from mere philosophical musing into a sprawling marketplace of hype, fraud, and pseudoscience.

In this post I will try to present a systematic overview of the full spectrum of quantum-related misinformation growing in the market today. I already wrote a “Quantum Baloney Detection Toolkit” a few years ago, but I decided it needs and update and a different angle. Because the situation is only getting worse.

The proliferation of quantum flapdoodle is not accidental. It is driven by a perfect storm: the convergence of AI hype, urgent government mandates for quantum-resistant cybersecurity, and unprecedented access for retail investors to speculative markets.

A Field Guide to Quantum BS – Hype, Scams, and Snake Oil

The gap between the hard reality of quantum engineering and the sensational way it’s often portrayed has created a fertile breeding ground for misinformation and fraud. It ranges from innocuous exaggeration, to willful marketing spin, to serious financial scams and wild pseudoscience.

Think of it as a “know your enemy” for quantum professionals: if you can spot these patterns, you’re less likely to fall for them or waste time (or money) on them.

Category 1: The Hype Bubble – When Marketing and Money Drive Exaggeration

At the mild end of the spectrum is what might be called hype inflation, usually driven by the startup funding environment. Startups need funding, and VCs often demand optimistic projections. This leads to systematic exaggeration in press releases, talks, and whitepapers.

At Applied Quantum we often get called by the investors to help them cut through exaggerations and hype and give them a realistic view of the technology.

Classic signs of hype bubble behavior: Companies talk about “revolutionizing X” long before basic milestones are reached; they focus on easy-to-understand metrics (qubit count, “quantum volume” scores) while glossing over caveats; they announce partnerships and “user programs” that generate buzz but little tangible progress. Often, revenue is primarily from government grants or from “quantum consulting” gigs (getting paid to explain quantum to other companies) rather than any product. Too many companies in the quantum industry take advantage of investors’ lack of physics knowledge and focus solely on generating fanfare to raise more money.

Now, hype isn’t a crime – and some level of optimism is to be expected in a cutting-edge field. But it becomes dangerous when it obscures reality so much that it misleads decision-makers and the public. One risk is a “quantum winter“: if hype grows into unrealistic expectations, the inevitable disappointments could sour funding and public support for the whole field (including the legit efforts). So managing expectations is actually important for the industry’s health.

The best defense here is education: ensure stakeholders understand the actual state of quantum tech so they can sniff out when a claim seems too good to be true.

A cybersecurity professional might encounter this hype in, say, vendor pitches. Example: A startup claims, “Our quantum cloud can solve your optimization problems 100x faster than classical computers!” – but in fine print it’s a very narrow benchmark or simply not true.

Question to ask: Has this claim been published or benchmarked by an independent group? Are they solving a practical problem or a contrived demo? If it’s only the latter, take it with a large grain of salt.

Category 2: The “Breakthrough” Mirage – Misleading or Misinterpreted Milestones

This category involves real scientific developments that get blown out of proportion (often by PR or media misunderstanding). I am not calling out the companies here, because they do do cutting edge and useful development, but I am calling out their marketing and PR departments. Two, out of many, industry examples:

D-Wave’s “First Quantum Computer” (2007)

Canadian company D-Wave Systems caused a sensation in 2007 by announcing what they called the first commercial quantum computer. They did demonstrate a 16-qubit device and later sold systems to the likes of Lockheed Martin and Google.

The catch: D-Wave’s machines are quantum annealers, not general gate-based quantum computers. They’re specialized to solve optimization problems by essentially finding low-energy states of a system. For years, whether D-Wave’s devices were truly exploiting quantum effects for speedup was hotly debated. Many experts were skeptical. Over time, evidence did show D-Wave devices perform quantum tunneling and entanglement, but the practical advantage remained elusive.

Bottom line: D-Wave does make novel machines that can be useful for very specific tasks, but calling them general quantum computers was misleading. The marketing in 2007-2010 created confusion that took years to unwind, with many non-experts thinking quantum computing had already arrived in full.

The lesson: beware of “first!” or “world’s biggest quantum computer!” announcements without context. Often there are important nuances (e.g., type of quantum computer, what it can or cannot do) that get buried.

Google’s “Quantum Supremacy” (2019)

This is a case where a correct scientific result got a bit lost in translation. Google’s research team in 2019 performed a carefully designed experiment with their 53-qubit Sycamore processor, showing it could sample from a random quantum circuit in 200 seconds – an esoteric task they estimated would take 10,000 years on the best classical supercomputer.

In quantum computing terminology, this was a landmark: the first demonstration of quantum supremacy, meaning a quantum device doing something that is infeasible for any classical computer. The media, however, often portrayed it as “quantum computer now faster than supercomputers” in general. IBM quickly contested Google’s claim by showing that with a different approach, a classical supercomputer (their Summit machine) could do the task in 2.5 days, not 10,000 years. While 2.5 days is still much slower than 200 seconds, it’s not the chasm originally reported.

More importantly, the task Google did had no practical value – it was a stunt (random circuit sampling was chosen specifically because it’s hard for classical computers but suits quantum). So the public heard “quantum computer surpasses classical,” and many assumed useful breakthroughs like breaking encryption or solving big problems were at hand, which was not the case. Even within the field, some bristled at the term “supremacy,” as it fed hype.

The reality: Google’s experiment was a big scientific deal and a positive milestone. But it didn’t change the day-to-day capabilities of quantum computers one iota for real applications. IBM’s response and others noted that context matters – how you frame a result can mislead.

When you hear claims like “quantum computer solves problem X that would take classical Y years,” ask: what was the problem, really? If it’s something contrived or not directly useful, then it’s more of a proof-of-concept than a revolution. Beware of milestones being presented without caveats.

Category 3: Quantum Scams and Frauds – When Hype Crosses into Deception

Next, we move from exaggeration to deliberate deception for profit. Unfortunately, the complexity and excitement of quantum have also attracted outright scammers – people and companies making false claims to swindle investors or customers. Here are two illustrative cases:

The “Phantom Photonic Chip Foundry” – Quantum Computing Inc. (QCI)

Quantum Computing Inc. (QCI) (NASDAQ: QUBT) is a small publicly-traded company that has in recent years made grand claims about its quantum technology. In 2023-2024, it announced it was building “the nation’s first dedicated quantum photonic chip foundry” in Arizona and had big orders lined up. Sounds impressive – a foundry implies a high-tech semiconductor fabrication facility. They even gave an address in Tempe, AZ for this foundry and touted partnerships (even suggesting a strategic tie with NASA) to bolster their credibility.

(Disclosure: No position in companies mentioned as of publication. Based on public sources. Opinions only. Not investment, legal, or tax advice.)

What was the reality? Investigative research firms (like Iceberg Research and Capybara Research, who specialize in short selling) looked into QCI and found a house of cards. The address of the “foundry” in Tempe turned out to be a nondescript office suite in an Arizona State University research park – no manufacturing equipment, no cleanroom, not even a loading dock for moving silicon wafers. Building management reportedly confirmed “there was no foundry there” at all. One investigator who visited saw just people in a conference room; the “facility” was basically an empty office. In other words, QCI appeared to have fabricated a major infrastructure claim out of thin air.

It gets worse. QCI’s supposed partnership with NASA? According to the short-seller report, NASA had only a single $26,000 contract with QCI for some basic software consulting, and “no relationship beyond” that. QCI also claimed revenues by selling to obscure entities that on closer inspection seemed to be related parties or shell companies, a classic trick to inflate sales. Iceberg Research bluntly labeled QCI a “perma-scam” that thrives on stock pumps with little substance.

For our purposes, the QCI saga is a cautionary tale: if a quantum company (especially a little-known one) makes claims that seem too good or grand to be true, investigate. Red flags include: minimal revenue but lots of stock promotion, sudden pivots in business model (QCI jumped from quantum software to “AI” to photonic hardware in short order), and lack of technical details or independent validation of claims. If they say they have a facility or breakthrough, see if you can find pictures, third-party partners, or publications. If not, be very skeptical. In QCI’s case, a single site visit debunked their core claim – something any serious investor or journalist could have done. The frothy market allowed them to skate by on buzzwords for a while.

Now, I don’t want to imply that you should trust short-sellers reports unreservedly. For instance, short-seller Scorpion Capital in 2022 accused IonQ, a publicly-traded true quantum computing company, of inflating its technical capabilities and revenue projections (calling it “a scam CV disguised as a company”). IonQ forcefully denied the allegations and many experts felt Scorpion’s report was overly harsh or inaccurate – IonQ does have real trapped-ion quantum computers.

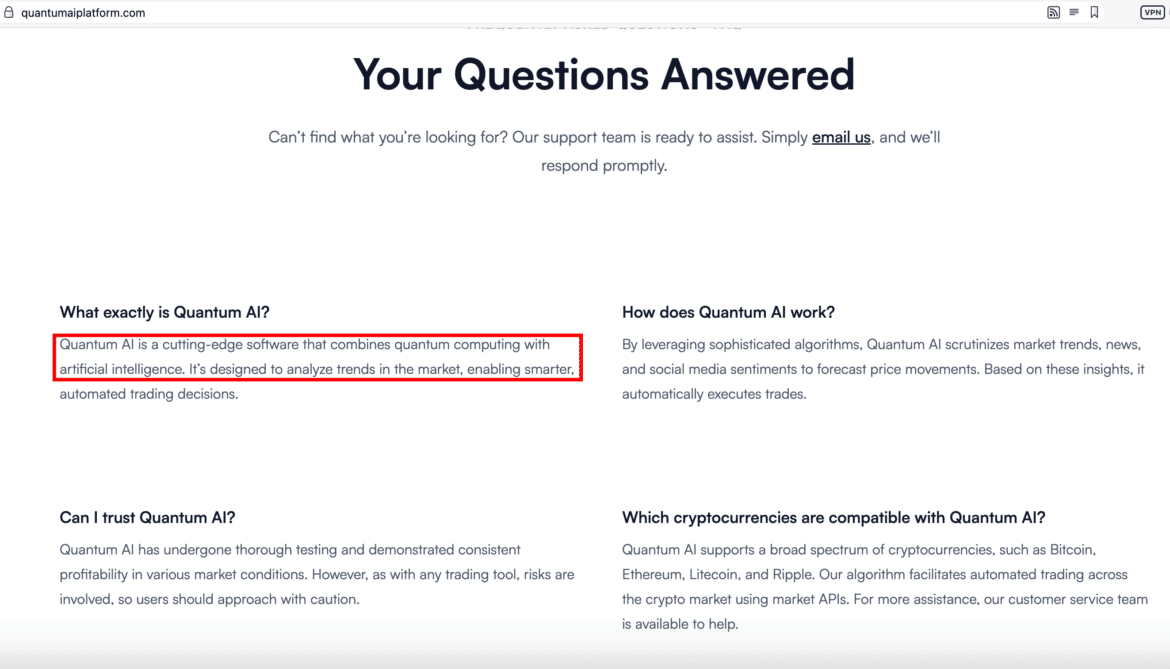

“Quantum AI” Trading Scam & Deepfakes

Not all scams target big investors; some target the general public’s FOMO. A prominent recent example is a network of cryptocurrency trading scams operating under names like “Quantum AI,” “Quantum Code,” etc. These scams promise a magical trading platform supposedly powered by quantum computing and AI that guarantees outlandish returns (e.g., “make $10,000 a day with zero risk!”). To lure people, the scammers have employed deepfake videos and fake news articles featuring celebrity endorsements. In one campaign, they created a deepfake of Elon Musk appearing to endorse the “Quantum AI” platform, and similarly used clips of other well-known figures like news anchor Tucker Carlson – all doctored to promote the scam.

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (ACCC) reported that in 2023, Australians lost over $8 million to these kinds of fake quantum trading platforms. In one case, an Australian man lost $80,000 after seeing a deepfake Elon Musk video on social media, signing up, and being conned by “account managers” who showed fake profits on a dashboard then disappeared when he tried to withdraw. The operation is sophisticated: they create entire fake news sites that mimic legit outlets (with URLs one letter off), post sponsored ads on Facebook (sometimes camouflaged as unrelated ads, like for vacuum cleaners, that redirect to the scam), and use high-pressure salespeople (often from overseas call centers) to hook victims once they express interest. Victims have also been tricked into installing remote desktop software under the guise of “setting up the trading algorithm,” which the scammers then use to steal more funds from their bank accounts.

Regulatory agencies around the world have been sounding the alarm. Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission explicitly warned that “Quantum AI” trading platform is a fraudulent scheme using Elon Musk’s image. The UK’s consumer advocacy group Which? investigated and found that Quantum AI is part of a global scam network, not a real investment service. The U.S. FTC and others have similarly warned about fake crypto investment platforms touting quantum computing. The use of the word “quantum” here is basically to invoke a sense of mystique and inevitability (“this is the future, don’t miss out!”) while preying on those who don’t really know what quantum computing is but have heard it’s revolutionary.

Key lesson: If someone is offering a guaranteed-return, secret algorithm investment – especially if it involves buzzwords like quantum – it’s almost certainly a scam. Real trading firms do use advanced algorithms, but no legitimate firm will promise overnight riches with no risk. And no consumer-accessible quantum computer exists yet – certainly not one that can predict markets! The mention of quantum here is pure marketing fiction.

Category 4: “Quantum Woo” – Pseudoscience and Conspiracy Theories

Finally, at the far end of the spectrum, we have the truly bizarre stuff – the abuse of the word “quantum” to sell all manner of snake oil, or to fuel conspiracy theories. Physicist Murray Gell-Mann once quipped about “quantum flapdoodle” – nonsense that uses quantum jargon to sound profound. Unfortunately, quantum flapdoodle is alive and well:

- Quantum Healing and Energy Gadgets: A plethora of alternative medicine and wellness products slap “quantum” on the label. Search online and you’ll find things like “quantum healing pendants”, “quantum magnetic resonance analyzers”, or even devices like the notorious “Quantum QXCI/SCIO machine”. That last one was a supposed medical device that claimed to diagnose and cure diseases with quantum energy; its inventor basically built a biofeedback scam and made millions until the FDA and law enforcement shut it down (after it literally contributed to patient deaths by diverting them from real medicine). Modern versions still pop up – stickers that claim to use “quantum frequencies” to protect you from 5G, patches infused with “quantum energy” to heal pain, etc. These products typically misuse some real scientific terms (quantum, frequency, energy) in a completely nonsensical way. For example, one pendant’s marketing said it “uses quantum resonance to balance the body’s energy frequency.” This is techno-babble. There is no quantum mechanism that would make a piece of jewelry improve your health. At best, these are placebos; at worst, they’re dangerous if they dissuade people from proven treatments. The presence of quantum in health scams is just the latest incarnation of what we’ve seen before with words like “magnetic” or “homeopathic” – it sounds sciencey, so it sells.

- “Med Beds” and Miracle Cures: A conspiracy theory that has circulated in fringe groups (often overlapping with UFO or political conspiracies) is the idea of quantum med-beds – basically sci-fi healing pods that can cure any ailment instantaneously. Social media posts (often accompanied by AI-generated images of futuristic pods) have claimed that secret quantum med beds exist (sometimes attributing them to government or alien technology) and that they use a mixture of “quantum energy,” “tachyons,” “plasma,” and other buzzwords to regenerate organs or reverse aging. Needless to say, this is pure science fiction. No such technology exists. It’s the kind of thing one might see on Star Trek, but people are spreading it as if it’s real and being hidden from the public. These med bed rumors have been debunked by scientists as having no credible basis. They persist in some corners of the internet, though, and unfortunately some seriously ill people have been led to believe a miraculous cure is being kept from them – a cruel false hope.

- Quantum Consciousness and Spirituality: A more subtle but pervasive misuse of quantum concepts is in the realm of New Age spirituality. Ever heard someone say “we are all connected because of quantum entanglement” or “you can manifest reality because the observer effect in quantum physics means consciousness collapses the wavefunction”? There’s a whole genre of pseudo-philosophy books and seminars built on taking the weirdness of quantum mechanics and stretching it into metaphysical claims. While it’s true quantum physics is deeply non-intuitive and does challenge our classical worldview, there is zero scientific evidence that it can be used to explain consciousness or that thinking a certain way can directly influence physical reality by quantum means. Assertions like “quantum vibrations in microtubules explain consciousness” (a disputed hypothesis by Roger Penrose and Stuart Hameroff) remain highly speculative and even if true wouldn’t give you mental superpowers. “Quantum” here becomes a new mysticism – ironically the very thing Einstein feared when he said “God does not play dice” (he worried people would invoke mysticism to explain quantum randomness).

The common thread with quantum woo is a vocabulary hijack: using legitimate scientific terms outside their domain of validity. If you don’t know what those terms mean, the statements can sound profound. But to a physicist, they usually range from meaningless to outright hilarious. As a cybersecurity pro or technologist, why should you care about this fringe stuff? Two reasons: First, it can sometimes creep into professional settings (e.g., a consultant might push a “quantum-inspired” encryption that is actually snake oil; or an executive might be taken in by a buzzword-filled proposal). Second, it contributes to general confusion and skepticism – when people see obvious nonsense labeled quantum, they may start dismissing the real science too. It pollutes the discourse.

One way to visualize the ecosystem of quantum misinformation is as a pyramid or continuum:

- At the base, we have real quantum science – counterintuitive but experimentally verified phenomena like superposition and entanglement. These are genuinely fascinating and can sound mystical if you’re not used to them.

- In the middle, corporate PR and media take those real phenomena and simplify or exaggerate them to make headlines or attract investment (e.g., “quantum computer simultaneously in multiple states tries all solutions at once!” – a half-truth often used to explain quantum computing). This creates an inflated public perception of what’s happening.

- Riding on that inflated perception, fraudsters and opportunists craft schemes that sound plausible to the layperson (“invest in our quantum AI startup, we’re ahead of Google!” or “buy this quantum health device”). They exploit the fact that a kernel of truth in the lower layers can lend credibility to their false claims.

- At the top, the most extreme grifters and true believers push ideas that are completely untethered from reality (med beds, perpetual motion machines powered by quantum energy, etc.), which often find an audience in those already primed by the lower levels of misinformation.

In short, minor exaggerations can soften the ground for major scams. A corporate press release that overhypes might be relatively harmless itself, but it contributes to a general environment where a fake “quantum breakthrough” can gain traction before experts debunk it.

The takeaway for readers is to cultivate a quantum BS detector.

Staying Sane Amid the Hype

It’s easy to get overwhelmed (or cynical) after surveying the landscape of quantum hype and scams. You might be thinking: Is there any real value here, or is it all smoke and mirrors? Rest assured, quantum computing is a real field with real potential. The vast majority of researchers and engineers in it are earnest, brilliant people working on one of the hardest problems of our time. We will likely see tremendous breakthroughs in the long run. But as with many emerging technologies, the early years can be rocky – full of exaggerated promises, uncertainty, and yes, opportunists.

For cybersecurity and IT professionals, the challenge is to navigate this minefield wisely: prepare for the genuine quantum threat without getting caught up in nonsense. So, how can we do that? Let’s distill a few practical guidelines and tools:

1. Prioritize the Real Threat – Focus on HNDL and PQC Migration Now

As discussed your number one quantum-related security task today is dealing with the Harvest Now, Decrypt Later risk. That means begin your transition to quantum-resistant cryptography sooner rather than later. Start by identifying what data in your organization has a long confidentiality lifespan (5, 10, 20+ years). Examples: long-term intellectual property, customer PII that must be kept private, government or defense-related data, healthcare records, etc. Then map out where that data is encrypted and what algorithms protect it. This crypto-inventory and data classification is step one. Step two is developing a roadmap to implement NIST-approved post-quantum algorithms in those high-priority areas, ideally achieving some level of crypto-agility (the ability to swap crypto systems without huge upheaval).

Remember that some transitions will be complex – for instance, upgrading the cryptography in embedded devices out in the field, or in systems that have infrequent update cycles. This is why starting now matters. Government regulators are already pushing this: e.g., the U.S. Office of Management and Budget set timelines for federal agencies to inventory cryptographic assets by 2023 and have a full plan by 2024, and to begin migrating systems by 2025 (goals which many agencies are struggling with). The private sector should mirror these efforts.

By focusing on this tangible task, you accomplish two things: you mitigate the most pressing risk, and you also insulate yourself from much of the hype. You’re not betting on when Q-Day is; you’re ensuring you’ll be ready whenever it comes. As Admiral Rogers’ quote underlined, if it needs to stay secret for decades, protect it now – solid, no-regret advice.

2. Develop Your Quantum BS Detector – Critical Questions to Ask

Whenever you encounter a new quantum computing claim, whether it’s in a vendor pitch, an article, or a conference talk, pause and apply a critical filter. Here are some key questions and red flags:

- Are they talking about physical qubits or logical qubits? If someone boasts “we have 500 qubits,” dig deeper. If those are noisy physical qubits with no error correction, the number alone means little. A claim involving even a handful of logical (error-corrected) qubits, on the other hand, would be significant. Many scams and overhyped claims will carefully avoid this distinction. If you only hear “qubits” without qualifiers, assume they are physical and ask about error rates.

- Is there a peer-reviewed paper or credible documentation? Real breakthroughs in quantum computing will almost always be accompanied by a scientific paper (often on the arXiv preprint server at minimum) with enough details for experts to evaluate. If a company claims a major advance but provides only a press release or marketing whitepaper with no technical details, be very skeptical. This was the case in that Chinese Schnorr algorithm incident – the initial preprint was highly technical, but many media outlets that covered it didn’t consult independent experts or wait for reviews. The inverse example: Google’s supremacy claim was published in Nature and immediately scrutinized by IBM and others. That’s healthy scientific process. Scammers, by contrast, avoid concrete, falsifiable details – they thrive in ambiguity.

- Does the claim solve a practical problem or just a contrived demo? We saw how Google’s supremacy was a contrived problem. Many quantum “advantages” reported so far are in the same boat – e.g., quantum annealers might solve carefully crafted spin glass problems faster than classical, but those problems aren’t ones businesses actually need solved. If someone says “quantum X outperforms classical Y by Z times,” ask: on what problem? If it’s something like factoring 21 or solving a synthetic math puzzle or a quantum chemistry computation for a very small molecule, that’s nice but not world-changing. The gold standard will be when a quantum solution beats the best classical solution on a useful, real-world problem (like a material science simulation or an optimization task with practical scale and complexity). We’re not there yet.

- Consider the source and context: Who is making the claim and why? A claim from NIST or a university lab comes with different motivations than a claim from a startup CEO on a fundraising tour. A vendor pushing a product might exaggerate or omit downsides. A short-seller might overstate problems to tank a stock. Always consider incentives. If NASA, for example, announces it achieved X with quantum, that’s likely credible (and NASA tends to be measured). If a tiny startup says they have a secret quantum device that IBM and Google somehow overlooked, raise eyebrows and demand proof.

- Watch out for buzzword salad: As mentioned in the scams section, nonsense phrases like “quantum blockchain AI” or mixing unrelated tech (“our quantum neural network on the blockchain will…”) are hallmarks of BS. Legit quantum technologists usually are very precise about terminology (because they’re often speaking to fellow scientists). If you see language that sounds like it’s generated by throwing every hot buzzword into a blender, that’s a bad sign. Similarly, claims that misunderstand basic principles (e.g., “our quantum computer tries all answers in parallel” – a common oversimplification that is not how it really works in terms of getting a single correct answer) indicate the person might not know what they’re talking about or assume the audience doesn’t.

- Check for independent validation or replication: If a company says, “we achieved X,” has anyone outside the company seen it or tested it? For hardware, this might be difficult if it’s proprietary, but credible companies often collaborate with researchers or at least allow some independent benchmarking. Quantum cloud services from IBM, IonQ, Rigetti, etc., can be accessed by external users who then publish on them. So if those companies exaggerated, the user community would call it out. On the flip side, companies that operate in a black box and only tout results internally could be hiding something. For instance, the allegations against IonQ were that their 11-qubit system’s performance was far worse than claimed and that the 32-qubit system they advertised didn’t truly exist yet. IonQ had published papers and a lot of technical detail in the past, which helped observers push back on some of Scorpion’s more extreme assertions. Transparency is your friend – lack of it should trigger caution.

For more on these, see “Quantum Baloney Detection Toolkit“.

Trust, But Verify – Stay Grounded in Physics and Engineering

Finally, in evaluating any quantum claim (or deciding when to worry about quantum threats), keep a level head grounded in the actual physics and engineering. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. If someone says tomorrow that they broke RSA with a laptop or they built a room-temperature quantum computer with a million qubits, your default should be “I’ll believe it when I see rigorous proof.” And that proof needs to be more than a slick demo; it needs to withstand global scrutiny from experts. Importantly, that skepticism cuts both ways: if a pundit says “quantum computers will never work” or “quantum is a bust,” you should also question that – many things thought “impossible” in one decade become normal in another. The prudent stance is neither blind optimism nor dismissive cynicism, but a kind of informed watchfulness.

One useful approach is to follow a few key experts who have a track record of honesty in the field. People like Scott Aaronson (quantum computing theorist known for debunking hype), John Preskill (who is enthusiastic but frank about challenges), Michele Mosca (who surveys experts to estimate timelines), and cryptographers like Bruce Schneier (who offers a security perspective). For instance, Aaronson often points out that while quantum computers are revolutionary, they won’t, say, “solve all NP-complete problems instantly” – a misconception sometimes seen. He advocates a balanced view: huge potential, but also hard limits and a lot of work between here and there. Staying up to date via such voices can help you filter the noise.

In the end, remember that the quantum revolution, if we call it that, will not happen overnight. It’s more of a dawning sunrise than a lightning strike. There won’t be a single day when suddenly all encryption fails and computers transcend classical limits in one swoop. Instead, we’ll see incremental progress: 50 noisy qubits become 100, then 1000; error rates drop from 1% to 0.1% to 0.01%; a few logical qubits appear; early quantum algorithms solve small instances of useful problems; scaling up further, more problems become tractable; eventually, a cryptographically relevant quantum computer emerges and is announced probably years after it was secretly achieved by a government agency. Each step on that road will come with engineering triumphs and lots of false alarms or dead ends.

Disclosure & Disclaimer: As of publication date, I do not hold positions in the securities mentioned. Content is derived from public sources believed reliable, but accuracy and completeness are not guaranteed. Views are my own and do not represent any employer or client. Nothing here is investment, legal, or tax advice, nor an offer or solicitation to buy or sell securities. I may initiate or change positions without notice. Where relevant, I will disclose any compensation, consulting, advisory, or speaking relationships with companies discussed.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.