Japan Launches First Homegrown Quantum Computer, Marking a Quantum Sovereignty Milestone

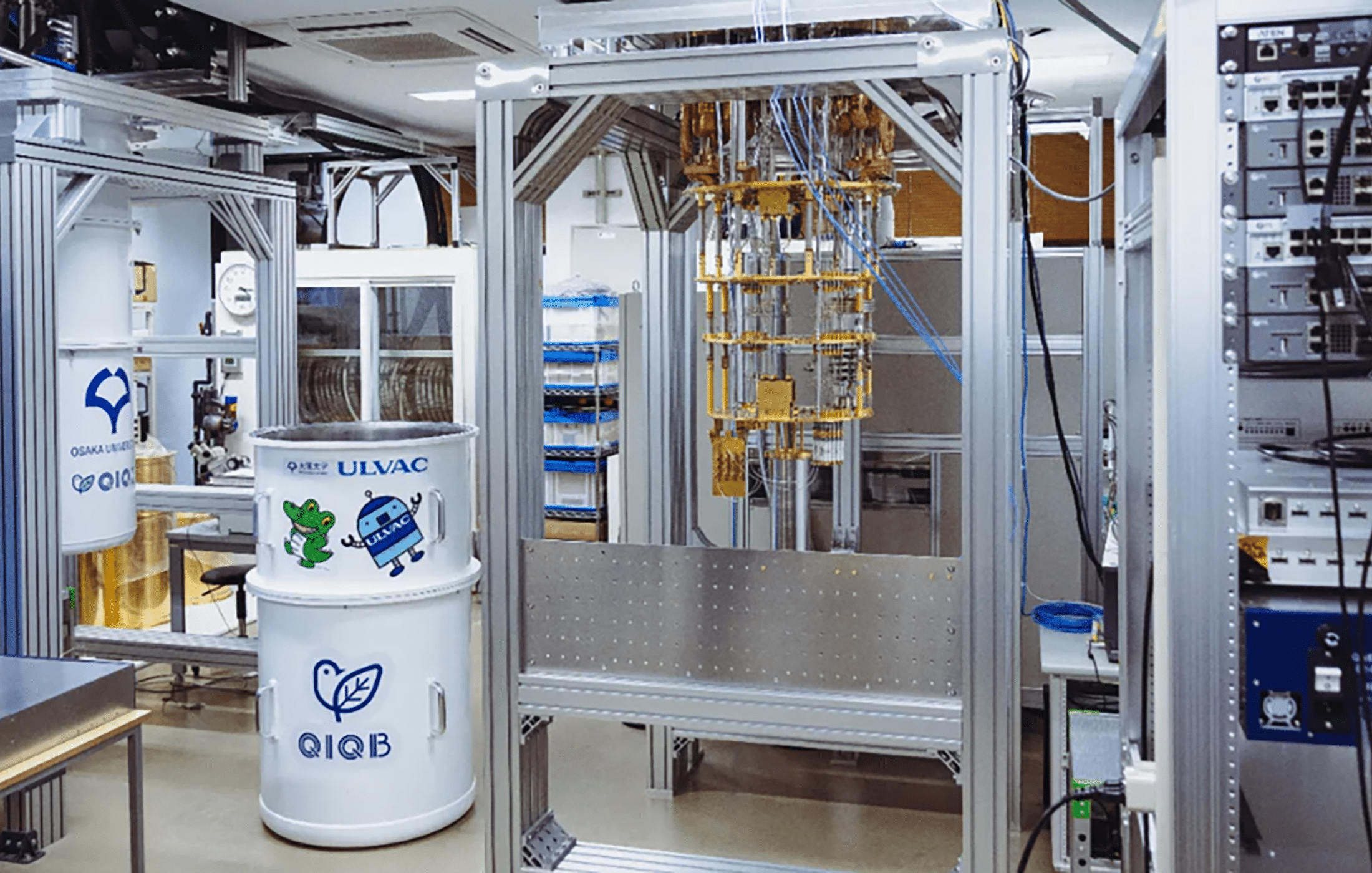

29 Aug, 2025 – Japan has officially switched on its first quantum computer built entirely with homegrown technology. The new superconducting system went live on July 28, 2025 at Osaka University’s Center for Quantum Information and Quantum Biology (QIQB) – a landmark achievement that makes Japan one of the few countries to develop a quantum computer without foreign components. University representatives confirmed that all previously imported hardware has been replaced with domestic alternatives, and the machine runs on a Japan-developed open-source software stack called OQTOPUS. In other words, every critical piece of this quantum computing stack – from the cryogenic refrigerator to the control electronics and the quantum chip itself – was designed and built in Japan.

This fully domestically produced quantum computer uses superconducting qubits housed in a specialized cryogenic setup. The quantum processing unit (QPU) was developed by the RIKEN research institute, leveraging Japan’s deep expertise in superconducting electronics. Achieving complete self-reliance meant rebuilding hardware that is usually sourced from a handful of specialized suppliers abroad. Notably, the team succeeded in manufacturing a key component – the ultra-cold dilution refrigerator that keeps the qubits at near absolute zero – within Japan for the first time. (Dilution refrigerators are often imported from overseas; building one domestically is a major feat in cryogenic engineering.) The project was a broad national collaboration spearheaded by QIQB in partnership with RIKEN and leading Japanese companies like ULVAC (a vacuum and cryogenics firm) and computing giant Fujitsu, among others. Backed by government funding, the effort demonstrates Japan’s capacity to design, manufacture, and integrate a complete quantum system on its own soil.

The new quantum computer was not only built in the lab – it was also publicly showcased soon after its launch. In mid-August 2025, Osaka hosted a special exhibit at Expo 2025 where visitors could see components of the domestically-built quantum computer and even interact with it via the cloud. The exhibit allowed attendees to run simple quantum programs remotely on the machine, while exploring interactive displays about quantum phenomena like entanglement. This public demo was designed to demystify the technology and highlight Japan’s achievement. Officials described it as a strategic step toward accelerating practical quantum applications and inspiring future innovators. In short, Japan’s quantum leap is now on full display – a proud moment for the country’s researchers and a notable development in the global tech landscape.

Why Japan’s Quantum Feat Matters: Sovereignty in the Quantum Era

Installation of Japan’s fully homegrown quantum computer in progress at Osaka University’s QIQB. All critical components of the system – from the cryogenic “chandelier” housing the qubits to the control electronics – were produced domestically, highlighting Japan’s quantum technology sovereignty.

Japan’s accomplishment is big news in the quantum computing world because it represents a triumph of technological sovereignty. In an era when advanced computing capabilities are seen as strategic assets, being able to build a full-stack quantum computer indigenously is a major advantage. Until now, only a very few nations have developed quantum computers without relying on foreign tech – and Japan has now joined that elite club. This achievement underscores how exceptional such capabilities are: Japan managed it only by leveraging a broad industrial base in precision electronics, semiconductor fabrication, materials science and other areas built up over decades. Few other countries possess such an ecosystem to draw on for a project this complex.

For context, the global race for quantum computing has so far been dominated by the United States and China, with Europe mounting a collective effort. The United States benefits from tech giants like IBM and Google, which have built some of the most advanced quantum processors in the world (IBM recently unveiled chips with 100+ qubits, for example). China, backed by massive state-led programs, has developed its own cutting-edge machines – including superconducting prototypes with 60+ qubits and even a 100-plus-qubit system in recent years. Meanwhile, the European Union also views quantum tech as vital for technological sovereignty, but Europe’s situation illustrates the difficulty of covering all bases independently. The EU boasts world-class quantum researchers and leading companies (for instance, startups in France and Germany building quantum chips, and a Finnish firm that dominates in quantum cryostats), yet it still lacks pieces like large-scale chip fabrication for quantum control electronics – infrastructure that exists mainly in the US and East Asia. The EU’s strategy explicitly calls for securing supply chains and building an “autonomous, sovereign, and competitive” quantum industry, but also candidly admits this is a tall order given today’s gaps. In practice, even Europe isn’t going it alone: the European Commission is diversifying partnerships with allies (including the US, Canada, Japan itself, and others) to share expertise and reduce dependencies.

The concept of “quantum sovereignty” – the ability for a nation to fully own and control its quantum technology – is increasingly important in geopolitics. Quantum computers are expected to unlock breakthroughs in fields like drug discovery, materials science, optimization and cryptography, potentially conferring huge economic and security benefits to those who harness them. It’s no wonder that governments want assured access to such strategic technology, without being at the mercy of another country’s exports or black-box components. Japan’s new machine is a direct assertion of that sovereignty: it runs on locally built hardware and software that Japan can trust and improve on its own terms. As Professor Makoto Negoro of QIQB put it during the launch, “We have demonstrated that Japan can create a fully domestically produced quantum computer with high performance”. Achieving this self-reliance has both practical and symbolic significance – it means Japanese researchers and companies can experiment freely on a platform whose intellectual property and supply chain are under national control.

That said, Japan’s quantum sovereignty does not mean isolation from the global community. In fact, the project’s success was enabled by international knowledge exchange (Japan has been collaborating with IBM and others for years, gaining know-how) and the continued participation of Japanese companies in worldwide quantum initiatives. Even now, Japanese teams will benefit from scientific exchanges and may source certain specialized materials from abroad as needed. This mirrors a broader truth: building a cutting-edge quantum computer requires such a wide array of expertise and infrastructure that virtually no one goes entirely solo. “A full-stack quantum buildout is prohibitively expensive and complex for all but perhaps two or three global powers – and even they face significant hurdles,” as one analysis noted. The U.S. and China might be those two superpowers with broad enough shoulders, and Japan has now shown it can be counted in this upper echelon. Other nations, from Canada to Australia to India, are investing in quantum R&D too, but they typically focus on pieces of the puzzle (like software, photonics, or niche applications) or partner with allies, rather than attempting a fully homegrown system from scratch.

Japan’s feat therefore highlights both the importance and the rarity of true quantum independence. It sends a message that Japan intends to be a serious player in the coming quantum era, not merely by using others’ machines but by innovating at every level of the technology. This could give Japan a platform to accelerate research into practical quantum applications relevant to its industries (automotive, pharmaceuticals, finance, etc.) and to cultivate domestic talent in quantum engineering. It also aligns with national policy: the Japanese government designated 2025 as the start of “quantum industrialization” and has been funding programs to kickstart a homegrown quantum ecosystem. We can expect this momentum to continue, with Japanese companies and universities likely expanding on this design in the coming years.

At the same time, Japan’s approach exemplifies a balanced strategy that other countries are watching. Complete self-sufficiency in an advanced field like quantum computing is extremely difficult to achieve, and Japan’s accomplishment doesn’t mean the end of global cooperation – rather, it gives Japan more leverage and confidence within those collaborations. In Europe, for example, policymakers talk about pursuing “strategic autonomy” in quantum, but they also emphasize partnerships and open standards to avoid reinventing the wheel. Japan’s case shows that a country can assert a high degree of technological sovereignty (by building its own machine) while still remaining an active part of the international R&D network. In fact, Japan plans to invite global partners to use and benchmark against its system; Professor Negoro noted the aim is to “collaborate with global partners to position Japan at the forefront of this field worldwide”.

In conclusion, the launch of Japan’s first fully homegrown quantum computer is far more than just a one-off news event – it’s a significant milestone in the global quantum race. It highlights the growing premium placed on quantum sovereignty, and the lengths to which a nation will go to achieve it. Only a handful of economies can even contemplate such an endeavor with domestic resources, and Japan’s success required decades of groundwork in related high-tech industries.

This breakthrough not only bolsters Japan’s standing in quantum technology, but also sparks important conversations internationally about how to balance self-reliance with collaboration in pursuit of progress. The lesson for other countries? Building every part of a quantum computer at home may not be feasible for most, but investing in core strengths – and ensuring options to pivot if geopolitics or supply chains shift – will be key. Japan’s quantum computer is a shining example of that strategy in action, and a reminder that the race for quantum advantage is not just about qubits and algorithms, but also about who builds them, and where.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.