QuantWare’s “10,000‑qubit chip” headline: a real scaling bet – and why it still doesn’t mean Q‑Day

Table of Contents

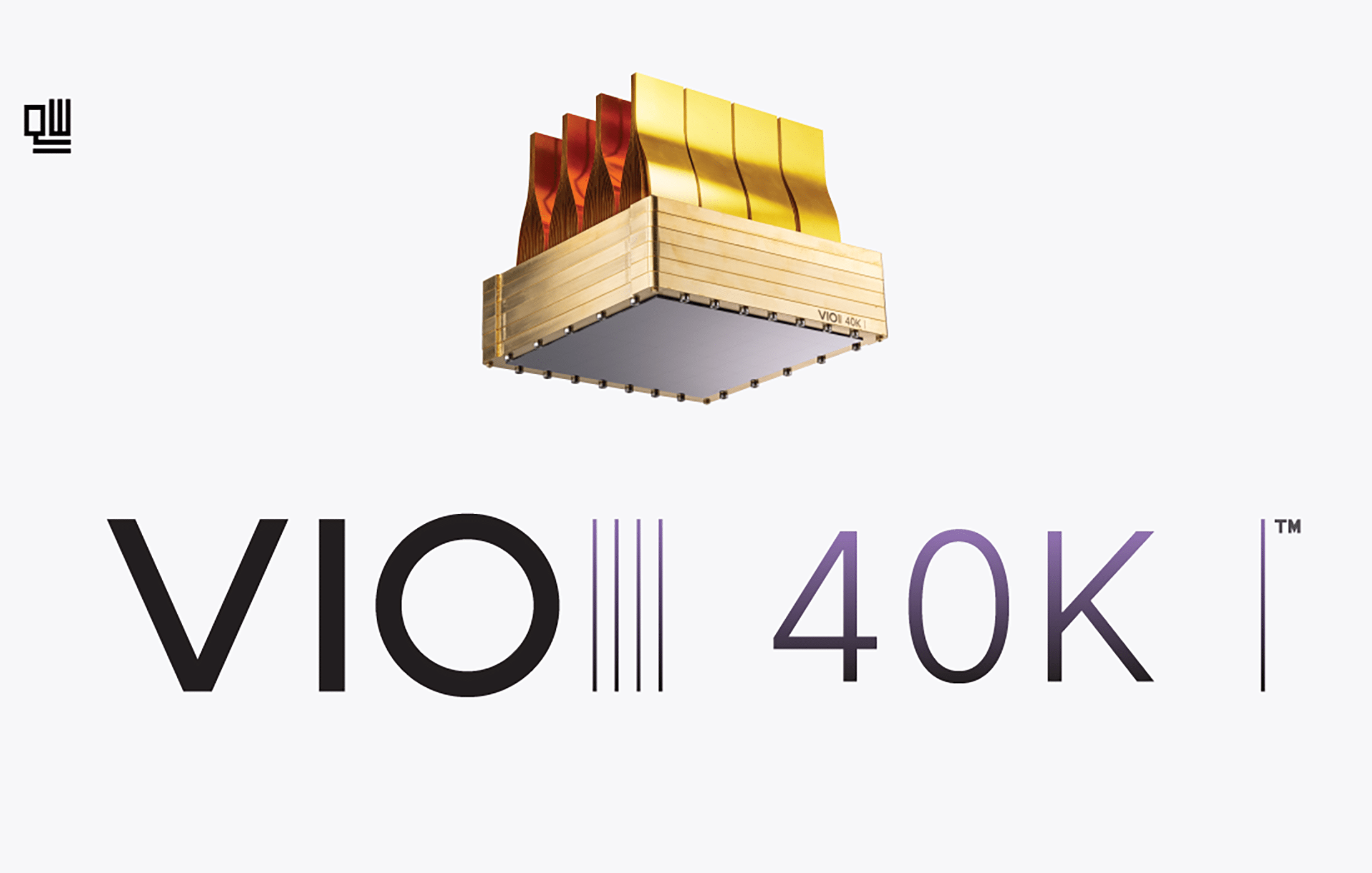

10 Dec, 2025 – Dutch startup QuantWare has announced VIO-40K™, a new 3D packaging architecture designed to build superconducting quantum processors with up to 10,000 qubits on a single device. This represents roughly a 100× increase over the scale of today’s largest superconducting chips.

The VIO-40K approach uses a stack of chiplets – multiple layers of quantum chips and interposer modules – to deliver control signals vertically into the qubits, rather than spreading extensive wiring across a flat chip surface. By going vertical, QuantWare aims to bypass the “I/O bottleneck” that has constrained 2D quantum chips (where thousands of control lines would otherwise consume precious area and introduce cross-talk between qubits). According to the company, VIO-40K supports 40,000 input-output lines and uses ultra-high-fidelity chip-to-chip connections between the stacked chiplets. This design, they claim, provides “exponentially more compute per dollar and per watt” compared to building equivalent capacity by networking many smaller processors together. In essence, VIO-40K is a blueprint for a KiloQubit-scale quantum processor implemented as a single integrated unit, addressing key scaling pain points like cryogenic wiring density and control electronics in the fridge.

In tandem with the VIO-40K architecture, QuantWare also announced it is building “KiloFab,” a dedicated quantum chip fabrication facility in Delft, the Netherlands, scheduled to open in 2026. KiloFab will be Europe’s first industrial-scale fab focused solely on quantum devices, specifically those following QuantWare’s open Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) standard. The new fab is expected to boost QuantWare’s production capacity 20× and enable the company to start shipping VIO-40K-based processors to customers by 2028. This is a strategic move to ensure that manufacturing capability keeps pace with the ambitious chip design.

QuantWare, which currently sells off-the-shelf superconducting qubit chips and QPU components, is betting that by standardizing modular, stackable quantum chips, it can serve as a key supplier for many organizations building quantum computers – much like how a semiconductor foundry supplies classical chips to the broader computing industry. By establishing its own fab, QuantWare reduces reliance on third-party foundries and aims to become a one-stop shop for large-scale quantum processor fabrication in Europe.

Why It Matters: Bypassing Bottlenecks to Scale Up Quantum Computing

If achieved, a 10,000-qubit superconducting processor would be a game-changer – far beyond the few-hundred-qubit prototypes currently available. Such a leap in qubit count could allow, for the first time, meaningful quantum error correction: encoding many physical qubits into more stable logical qubits that can run deep algorithms without being ruined by errors.

In practical terms, a chip on the scale of VIO-40K might tackle complex problems in chemistry, optimization, or machine learning that are out of reach today. QuantWare’s innovation directly addresses a known hardware hurdle: conventional 2D chip packaging can’t accommodate the control lines needed as qubit counts rise into the thousands (imagine trying to individually wire 10,000 qubits on a flat plane – it becomes impractical). By adopting a 3D chiplet approach (analogous to how classical semiconductors use 3D integration, like stacked memory or CPU chiplets), they aim to scale up qubit count without sacrificing qubit coherence or control fidelity. This aligns with broader trends in the semiconductor industry, where vertical integration is used to continue scaling when 2D layouts hit density limits.

Importantly, QuantWare’s plan could democratize access to large quantum processing units (QPUs). Rather than each major quantum computing player needing its own proprietary design and fabrication line to reach kilo-qubit scales, an open architecture available from a third-party supplier could allow smaller companies or research labs to obtain 10k-qubit processors simply by purchasing them. This “quantum processor as a product” model could accelerate the entire field by lowering the barrier to high-qubit-count hardware.

It also has geopolitical significance: KiloFab strengthens Europe’s position in the quantum race. An on-continent quantum fab means European companies and institutes won’t be as dependent on U.S. or Asian foundries for cutting-edge quantum chips, and it could spawn a local supply chain for quantum technology.

Another notable aspect is the inclusion of NVIDIA’s NVQLink and CUDA-Q platform in the VIO-40K ecosystem. QuantWare specifically highlighted that VIO-40K will be compatible with NVIDIA NVQLink, an open high-speed interconnect for coupling quantum processors with classical supercomputers, and NVIDIA’s CUDA-Q software stack. This implies a tight integration between the quantum chip and classical AI/ HPC hardware, pointing toward a hybrid quantum-classical computing approach. Fast, low-latency exchange of data between a 10k-qubit quantum processor and GPUs/CPUs could be critical for tasks like real-time quantum error correction or hybrid algorithms (e.g. variational quantum algorithms that require lots of classical processing in the loop). By planning for NVQLink, QuantWare is addressing the compute architecture beyond the quantum chip itself – recognizing that as qubit counts scale, so does the need for a powerful classical control and error-processing backend. Reducing latency and increasing bandwidth between the quantum and classical sides could significantly improve the overall performance of a large-scale quantum system.

Who’s QuantWare

QuantWare is a spin-off from TU Delft (QuTech) in the Netherlands, founded in 2021 by CEO Mattijs Rijlaarsdam and CTO Alessandro Bruno. Rijlaarsdam and Bruno’s vision is to create a quantum chip company that supplies devices to the broader industry, rather than building a full-stack quantum cloud service themselves. In just a couple of years, QuantWare has grown into what it calls “the highest-volume supplier” of quantum processors worldwide, with customers in more than 20 countries. For example, it has delivered a 64-qubit “Tenor” QPU that is slated to power Italy’s largest quantum computer. By adhering to an open Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) framework, they are rallying an ecosystem of partners – from cryogenics (dilution refrigerators) to control electronics (companies like Qblox, Quantum Machines, etc.) – around compatible interfaces and standards. This ecosystem approach means anyone adopting QOA-compliant components could mix-and-match with QuantWare’s chips, making integration easier.

The Netherlands, and the EU more broadly, have been investing heavily in quantum technology, and QuantWare’s dedicated fab (with government support likely in the mix) shows that this support is moving into building real infrastructure. If KiloFab becomes reality on the proposed timeline, it could attract collaborations or orders from major quantum players – perhaps even tech giants or government programs that need custom quantum chips but don’t want to build their own fabs. In that sense, QuantWare’s model is akin to how foundries like TSMC or GlobalFoundries serve the classical chip industry. QuantWare could become a foundry for quantum processors, supplying many different clients.

Of course, significant challenges remain: scaling to a 10,000-qubit device will test the limits of maintaining qubit coherence and low error rates across a huge chip (or chiplet stack), managing yield in fabrication (thousands of qubits means thousands of potential points of failure on a chip), and integrating the necessary error correction capabilities so that those qubits can be useful. The timeline – with first VIO-40K devices in 2028 – is aggressive but not impossible if R&D breakthroughs continue at pace over the next few years.

Overall, QuantWare’s bold vision for KiloQubit processors and a quantum-dedicated fab represents a maturation of the quantum computing industry. It signals a shift from one-off laboratory feats toward semi-standardized manufacturing and scalable architectures. This announcement may also turn up competitive pressure on others: for instance, IBM has publicly discussed aiming for ~100,000 qubits by the end of the decade (with error-corrected “logical” qubits in the hundreds), and such roadmap goals will likely become more concrete as startups like QuantWare showcase their approaches.

In summary, QuantWare is tackling one of the critical roadblocks to large-scale quantum computing – and if their approach works, it could fast-forward the advent of truly large-scale quantum computers by making high-qubit-count hardware more readily available.

Putting the 10,000-Qubit News in Perspective

If you’ve been around quantum computing long enough, you know the pattern. A company drops a big qubit number; the headline travels faster than the footnotes; and a few hours later your inbox fills up with some variation of: “So… is Q Day here?” This week’s trigger was QuantWare’s announcement of VIO-40K – a new generation of its 3D scaling architecture that, in their words, enables 10,000-qubit superconducting processors with 40,000 input-output lines, built from chiplet modules linked by “ultra high fidelity” connections. QuantWare also said reservations are open now, with first devices shipping in 2028. The mainstream press coverage quickly crystallized into the familiar shorthand: “world’s first 10,000-qubit processor” and so on.

So let’s say the quiet part out loud, right up front: No, this does not mean cryptographically relevant quantum computing has arrived. It does not mean RSA-2048 encryption is about to fall, nor that “Q Day” (the day when quantum computers can break our public-key cryptography) is here. It doesn’t mean you should halt your post-quantum cryptography migration plans because “quantum winter came back,” and it doesn’t mean you need to sprint into panic mode because “the crypto apocalypse is next Tuesday.”

But – and this is important – it does mean something. And that “something” is important precisely because it lives in the unglamorous layer of quantum engineering that usually gets skipped in the first wave of headlines.

What QuantWare Actually Announced (and What They’re Really Selling)

QuantWare is positioning VIO-40K less as a single chip and more as a scaling architecture for superconducting quantum systems – essentially, a way to break through the geometric, wiring, and packaging ceilings that start to dominate once you try to move beyond “impressive lab device” into “system you can actually build and operate repeatedly.”

Their explanation is blunt: in today’s 2D superconducting layouts, routing and wiring for control signals consume most of the chip area. In fact, QuantWare claims that in current QPU designs, almost 90% of the chip area is eaten up by signal routing, not qubits (leaving only ~10% for the qubits themselves). This is a big reason the industry has been stuck at around ~100-200 qubits per chip for years – you simply run out of space and signal fidelity when you try to scale up further on a single plane. In QuantWare’s framing, adding more qubits in 2D causes a “fan-out” explosion: each additional qubit needs control lines that take up space and introduce cross-talk, and the problem worsens non-linearly as qubit count grows.

VIO-40K’s core promise is to change that equation by delivering signals in 3D, effectively eliminating the fan-out problem. Instead of spreading control wiring across the chip alongside the qubits, VIO-40K delivers control lines vertically through a stack of chiplets. This means you don’t have miles of microwires snaking around the surface; the control infrastructure comes in from above/below in a layered structure. If you stop wasting most of the chip area on wiring, you can let qubits dominate the area again – and prevent routing density from blowing up as you scale to thousands of qubits.

The architecture is also described as modular, but crucially, designed to behave like one continuous qubit plane. By freeing the chip edges from needing to host hundreds of bond pads or connectors (since signals are delivered vertically), QuantWare can tile multiple chiplets together with direct chip-to-chip links. They claim these links are “ultra-high-fidelity,” so that the boundaries between chiplets don’t significantly erode quantum coherence. In effect, they propose stitching smaller quantum chips into a larger one without the usual downsides of having to route signals out at the edges.

Finally, QuantWare makes a very explicit system-level claim: their design would allow 10,000 qubits in a single QPU, housed in a single cryostat, enabled by those “up to 40,000 I/O lines” and an architecture “optimized for high heat transfer capacity” (i.e., managing the heat load of all those signals in one fridge). In non-engineering terms, they’re saying you could build a single dilution refrigerator system that holds one 10k-qubit processor, rather than needing a data center full of dozens of smaller quantum systems wired together. This speaks to practical deployment: one big machine is easier to manage (and cheaper per qubit) than ten or twenty smaller ones, if you can make it work.

For those used to quantum computing announcements that are mostly about quantum algorithms or software, this one is unusually grounded in gritty hardware bottlenecks: wiring density, packaging constraints, cryogenic heat loads, and the nightmare of scaling up without a “fridge farm.” QuantWare essentially said: the qubit physics aren’t the only issue now – packaging and I/O are the critical path, and we have a product to solve that.

They also wrapped the news in an “ecosystem” narrative. In its press release, the company noted that VIO is available to the wider industry (tied to the Quantum Open Architecture concept), inviting others to adopt it as a standard scaling solution. And they name-checked NVIDIA’s NVQLink as part of a “VIO-40K compatible ecosystem,” positioning NVQLink as an open platform to build logical QPUs with tight quantum-classical integration (using NVIDIA’s CUDA-Q for the software stack). In other words, QuantWare is not just selling a chip; it’s selling the scaling approach and trying to make it an industry standard. The announcement of building KiloFab in Delft is part of the same story – it says, we’re serious about manufacturing at scale, not just one-off demos. KiloFab would allow them to produce these complex 3D stacked chips in quantity by 2028 , which is essential if you plan to actually deliver 10k-qubit processors to multiple customers.

Summing up the announcement in plain terms: QuantWare is betting that packaging and wiring – not qubit physics alone – are now the biggest hurdles to kilo-qubit quantum computers. And it’s trying to productize a solution to that, on a 2026-2028 timeline. This is a very different emphasis than, say, touting a new record fidelity or a novel qubit design. It’s saying the road to 10,000 qubits is mainly blocked by engineering challenges, and they have a way to unblock it.

Not Just Hype: QuantWare’s Credibility (and the Marketing Dial Turned Up)

Whenever a startup makes a bold claim (especially a 100× leap in qubit count), a reasonable question is: How credible is this, or is it just hype? On that front, it’s worth noting that QuantWare is not a random hype machine that came out of nowhere. They’re a Delft-based team that launched in 2021 out of one of the world’s top quantum research hubs (QuTech at TU Delft). Co-founder and CTO Alessandro Bruno isn’t a social media “quantum influencer” – he was the head of fabrication in the DiCarlo lab at QuTech, directly involved in building superconducting qubits. The company has been focused on selling quantum hardware components (not just promises) and by some accounts is already the highest-volume commercial supplier of quantum processors (albeit small ones) today. They have customers in over 20 countries and have publicly talked about delivering a 64-qubit QPU (named Tenor) that’s being used in an Italian quantum computing project. All that suggests they’re actually building things, not just slideware.

However – and this is an important caveat – in this VIO-40K announcement, QuantWare clearly turned the marketing volume up. Their press release explicitly claims the 10k-qubit scale is “100× larger than anything available in the industry today” and uses expansive language like “exponentially more powerful”. That kind of phrasing is exactly what causes the Q Day misunderstanding we discussed, because it blurs the line between “a bigger substrate” and “a machine that can break cryptography.” To most people, 100× more qubits sounds like 100× more computing power, which sounds like we might suddenly do things previously impossible. QuantWare surely knows that 10,000 physical qubits ≠ 10,000 useful error-corrected qubits, but the nuance can get lost when marketing leads with shiny numbers.

In short, QuantWare has real technical chops and a real product roadmap, but they also engaged in a bit of headline hyperbole here. It’s not outright vaporware, but it’s aggressively framed. And drawing that distinction – between credible effort and overhyped implications – is crucial for what comes next.

The “Q Day” Question: Why 10,000 Qubits ≠ Cryptographically Relevant

When someone asks “is Q Day here?”, they’re really asking whether we’ve crossed the threshold into cryptographically relevant quantum computing (CRQC) – meaning a quantum computer capable of running Shor’s algorithm (or other quantum attacks) at a scale that can break RSA-2048 or comparable cryptography in a reasonable time frame. In other words, they want to know if this 10,000-qubit development means we need to panic about our encryption.

This is exactly why I and others emphasize looking at logical qubits and fault-tolerant operations, not just the raw physical qubit count. A big part of my work has been developing a CRQC Capability Framework that forces us to ask: What is the logical qubit capacity of this device? What’s the error rate and overhead for error correction? How many logical operations can it run reliably? – rather than treating “qubits” as a simple scoreboard. Because history has shown that headline qubit counts are a terrible proxy for cryptanalytic capability.

So, let’s put QuantWare’s announcement into that lens. VIO-40K is fundamentally a story about the physical and engineering layer – about wiring and packaging enabling more physical qubits in one system. It is not, at least publicly, a claim that they have thousands of logical qubits with error rates low enough and runtimes long enough to factor large integers or run arbitrary algorithms. Nothing in their release talks about demonstrated two-qubit gate fidelities across 10k qubits, or logical error rates achieved, etc. It’s all about the potential to host more qubits in one device.

And if we anchor ourselves to the best current public estimates for breaking RSA, the mismatch in scale becomes obvious. Perhaps the most important recent analysis in this area is by Craig Gidney (Google Quantum AI), who in 2025 published a preprint titled “How to factor 2048-bit RSA integers with less than a million noisy qubits.” In that paper, Gidney estimates that under certain reasonable assumptions (surface code error correction, physical gate error rate of 0.1%, 1 µs cycle time, 10 µs feedback latency), one could factor a 2048-bit RSA number in under a week using <1,000,000 physical qubits. Yes, one million noisy qubits to break RSA-2048 in about a week. That was a significant update (down from some earlier estimates in 2019 that suggested ~20 million qubits for an 8-hour factoring). It tightened the target by roughly 20× through various algorithmic and coding improvements. But it’s still on the order of a million qubits for a single calculation in a week.

Now compare those scales coldly:

- QuantWare’s announced milestone: ~10,000 physical qubits (with first devices planned in 2028).

- Gidney’s conservative CRQC estimate: ~1,000,000 physical qubits (with error correction) to factor RSA-2048 in <1 week.

That’s a two order of magnitude gap in raw qubit count right off the bat. And that’s before we even talk about how many of those 10,000 qubits would be needed to encode a single logical qubit (with error correction overhead), or the additional overhead for magic state factories, or the classical decoding hardware needed, or the fact that you’d need the system to run continuously for days. Those “before we even talk about…” items are exactly where most quantum roadmaps quietly struggle. To break RSA, having 10k physical qubits means very little if their error rates are too high – you might only get a handful of logical qubits out of them, which is nowhere near what’s needed for Shor’s algorithm.

So, when someone asks me whether a 10k-qubit announcement means Q Day is here, my answer is: No – it doesn’t even clear the first quantitative hurdle implied by current attack estimates. It’s not close, and that’s not because 10k isn’t a lot (it is!), but because a cryptographically relevant quantum computer is a different class of machine entirely. It’s not just about qubit count; it’s about the whole system’s ability to implement a huge, error-corrected circuit.

Breaking Bottlenecks vs. Breaking RSA

Where QuantWare’s announcement does matter is in what it implies about the pace of progress in scaling the hardware substrate. In other words, it’s interesting not for immediate cryptanalysis, but for how it might accelerate the timeline toward larger machines.

Superconducting quantum computing has always been somewhat haunted by a scaling irony: you can fabricate more qubits on a chip relatively easily (the processes aren’t that different for making a 100-qubit chip or a 1000-qubit chip in principle), but you can’t reach them cleanly with control and readout as the number grows. The joke is the qubits themselves could multiply, but then wiring becomes geometry, geometry becomes cross-talk, cross-talk becomes calibration hell, and calibration hell becomes unstable error rates. And unstable error rates ultimately destroy the dream of turning physical qubits into logical qubits via error correction.

QuantWare is essentially saying: we can break that vicious loop by changing the physical architecture of the chip. Instead of spreading control lines across the same plane as the qubits (and snaking out to room temperature), deliver signals vertically in a 3D architecture. Keep the routing density under control by going up, not out. Free up the edges of the chip (since you don’t need a hundred coax connectors around the perimeter) so that chiplets can connect seamlessly and act like one large chip. It’s a “physics meets packaging meets manufacturability” solution to a very practical problem.

If this works as advertised, it’s meaningful because it attacks one of the most stubborn non-algorithmic constraints in superconducting quantum scaling. It’s not a new algorithm or a new qubit type; it’s a way to build a bigger machine without it collapsing under its own complexity. This kind of innovation doesn’t sound as sexy as, say, a breakthrough in qubit coherence time, but it is arguably just as important for the endgame – which is not about having the best qubit in isolation, but about having a huge ensemble of qubits all working together as a computer.

However – and here’s where caution comes in – a wiring architecture, no matter how clever, does not automatically translate to logical qubits. It translates to potential. The conversion of that potential into actual cryptanalytic capability depends on a bunch of system-level achievements that a press release won’t detail: Can you maintain below-threshold error rates across a device this large? Can you perform frequent calibration and crosstalk mitigation on tens of thousands of control lines? Can you run quantum error correction cycles (syndrome measurements, feedback, resets) in real-time across 10k qubits and keep everything phase-synchronized? Can you decode the stream of error syndrome data fast enough (likely on classical co-processors) to correct errors on the fly? And can you keep the whole contraption stable not just for seconds, but for the hours or days that a full algorithm might require?

Those are big questions. They are where the rubber meets the road in turning physical qubits into logical, fault-tolerant qubits. And nothing in the VIO-40K announcement answers them yet – nor should it, because 10,000 qubits are still on paper for now. So my stance can be summarized in one sentence: VIO-40K is an upstream scaling breakthrough, not a downstream cryptanalytic breakthrough. It’s a promising improvement in the foundation of the system, but it doesn’t suddenly solve the hardest parts of using that system for something like breaking RSA.

Why 40,000 I/O Lines Are a Big Deal

If the headline number is “10,000 qubits,” the fine print includes “40,000 I/O lines.” That detail might actually be the more consequential part of the story for engineers. It means that for those 10k qubits, the architecture supports up to 40k control and readout connections – roughly 4 lines per qubit on average (which is in line with needing at least a microwave drive line and flux bias for each qubit, plus readout resonators, etc., times chiplets).

That ratio is a reminder that as we scale, the bottleneck is now increasingly on the classical side of the system: the control electronics, the signal delivery, the cryogenic amplification and filtering, the timing synchronization, and the sheer physical act of getting 40,000 wires (or coax or waveguides) into and out of a cryostat. Managing 40k I/O lines is like building an ISS-sized life-support system, but for qubits – it’s huge. It implies a level of automation and engineering rigor well beyond what current ~100-qubit labs use.

In a small 5 or 50 qubit device, you can hand-tune each qubit’s pulses, and grad students (or automated routines) can painstakingly calibrate everything daily. In a 10,000-qubit device, you need a self-driving, automated nervous system to handle it. The moment someone says “40,000 lines,” they are implicitly saying “we believe the packaging, signal delivery, and thermal budget can support a regime where the control plane is as serious of an engineering project as the quantum plane.”

This is exactly the kind of progress that could compress timelines – not because it breaks cryptography directly, but because it makes “building larger machines” a less speculative undertaking. If QuantWare or others prove that you can indeed wire up and control 10k qubits in one go, then scaling to 50k or 100k might be more about replication and less about new physics. It moves the conversation from “can we ever build a machine that big?” to “how fast can we build the next one bigger?” That can have a profound effect on the pace of development.

The trick, of course, is that scaling the number of controllable qubits without degrading their fidelity is where a lot of quantum roadmaps quietly go to die. It’s not hard to fabricate 10,000 mediocre qubits. The hard part is to have 10,000 qubits that are all high-quality and can all be calibrated and operated simultaneously without the whole thing falling over. Every additional I/O line is also an additional source of heat (hence the note about “optimized for high heat transfer capacity” – you need to dump tens of milliwatts of heat per line at milliKelvin temperatures, which is nontrivial). More lines also mean more potential for cross-talk unless isolation is perfect.

So the technical question I care about most after this announcement isn’t “did they manage to put 10,000 qubits on one device?” but “can they preserve the full-stack error profile as they scale to that many qubits?” Right now, publicly, we don’t have enough detail to answer that – that’s something that will only become clear if and when prototypes or intermediate milestones are tested. Until then, the 40k I/O is both exciting and a bit daunting.

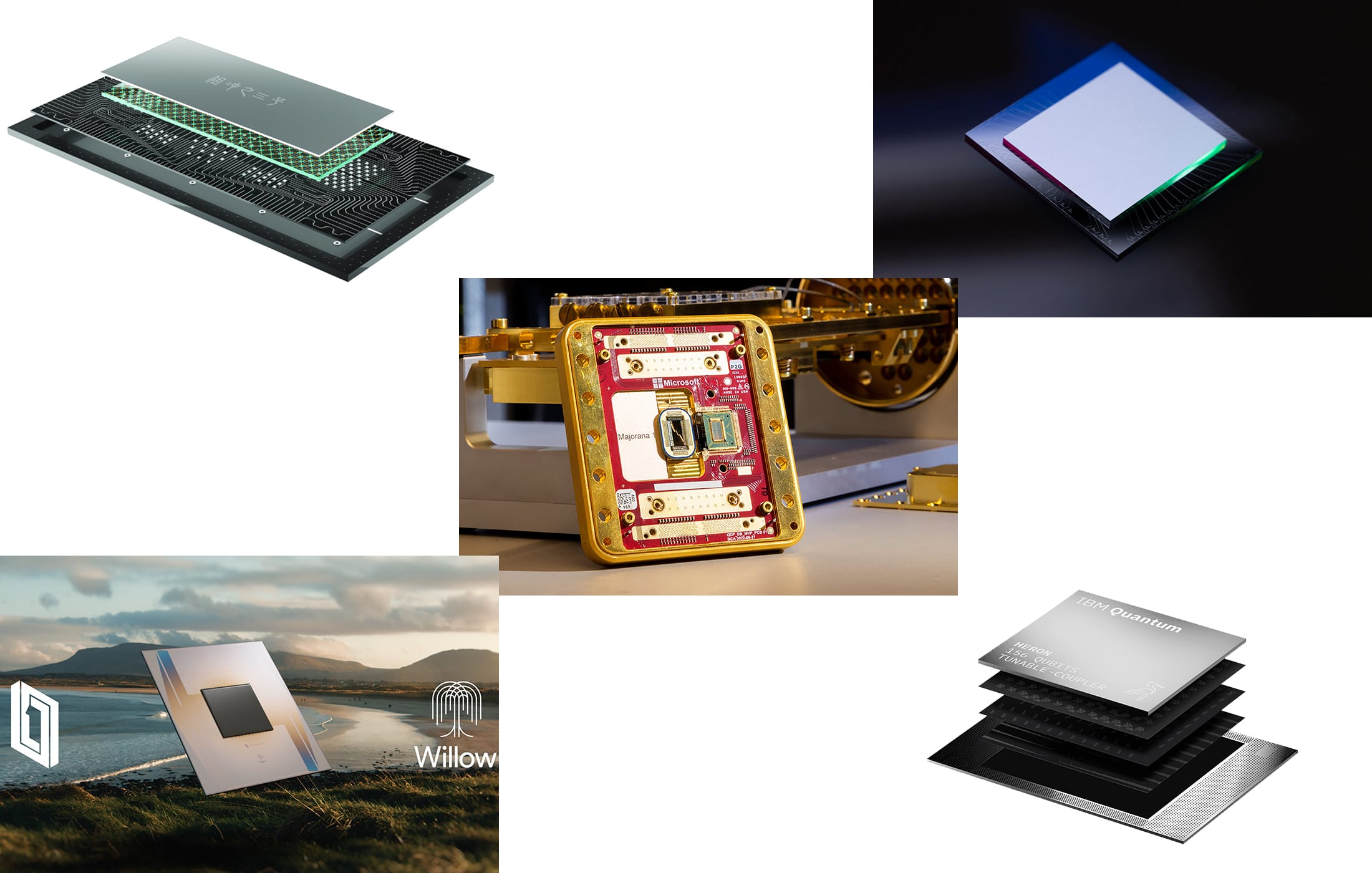

How Does 2028 Compare? IBM, IonQ, and PsiQuantum’s Roadmaps

Another reason I’m not treating this as “QuantWare suddenly leapfrogged everyone” is that the late 2020s were already getting crowded with ambitious quantum roadmaps – though each company talks in slightly different terms.

- IBM has been refreshingly explicit about fault tolerance in logical terms. IBM’s public roadmap says their first fault-tolerant system, codenamed “IBM Quantum* *Starling,” is targeted for 2029 and expected to run 100 million quantum gates on 200 logical qubits. In other words, by 2029 they want a machine that, at the logical level, can do 100 million operations on a space of 200 error-corrected qubits. That is still not an RSA-breaking machine by itself, but it’s a very different kind of claim than “we’ll have X physical qubits.” IBM is deliberately focusing on logical qubits and deep circuit depth because that’s what’s needed for useful algorithms. (They also plan to demonstrate smaller pieces earlier – e.g. by 2026 they target some form of quantum advantage with a 1,080-qubit modular system, etc., but the 2029 goal is the big fault-tolerance one.)

- IonQ, on the other hand, is explicit about both physical and logical scaling. In a 2025 roadmap update, IonQ announced a plan to reach over 2,000,000 physical qubits by 2030, which they say would translate to 40,000-80,000 logical qubits in their trapped-ion architecture. Those logical qubits assume a certain error-correcting code and overhead (they have mentioned an 80-200 physical-to-logical qubit ratio). They also broke down milestones: 102 qubits by 2024 (done), 1,024 by 2025 (in progress), 10k on a chip by 2027, 20k via two chips by 2028, and then ramping to 2 million by 2030 with photonic interconnects. Different technology (ions vs superconductors) and different challenges (they worry less about wiring density but more about networking fibers and perhaps cooling of traps), yet it shows a similar big picture: by 2028-2030, aim for tens of thousands to a million+ physical qubits and thousands of logical qubits.

- PsiQuantum, the photonic quantum computing startup, continues to frame its ambition around the million-qubit scale as well. They recently broke ground on a new site near Chicago intended to house what would eventually be the first million-qubit, fault-tolerant quantum computer in the U.S.. They have repeatedly said their goal is a million physical qubits with photonic interconnects to achieve full error correction, and they’re working on manufacturing techniques with GlobalFoundries, etc. According to Reuters, that Chicago facility (as part of the Illinois Quantum initiative) could host a “country’s first” million-qubit machine if all goes to plan. Their timeline isn’t publicly pinned to a specific year like 2028 or 2029, but they have hinted at progress before 2030 and recently raised another $1 billion to pursue it.

Placed against that landscape, QuantWare’s “first devices in 2028” doesn’t look like an outlier at all. In fact, it slots right into the general late-2020s time frame that many consider the dawn of small-scale fault-tolerant prototypes. The difference is in what layer of the stack each is emphasizing. QuantWare is pushing a solution at the hardware/package level to make superconducting qubits scale in one machine. IBM is pushing an end-to-end fault-tolerant architecture (including real-time decoding and modularity). IonQ is pushing both the sheer physical count and a path to logical qubits via ions and networking. PsiQuantum is pushing manufacturing and photonic integration for huge numbers.

In other words, QuantWare’s news is a legitimate data point in an industry-wide convergence toward demonstrating fault-tolerance by the end of this decade. But it is not, by itself, evidence that anyone has a cryptographically relevant machine in hand yet. If anything, it reinforces that everyone in the race sees the next 4-5 years as critical for scaling, and each is addressing a different piece of the puzzle.

QuantWare’s Roadmap: From 17 Qubits to 10,000 Qubits

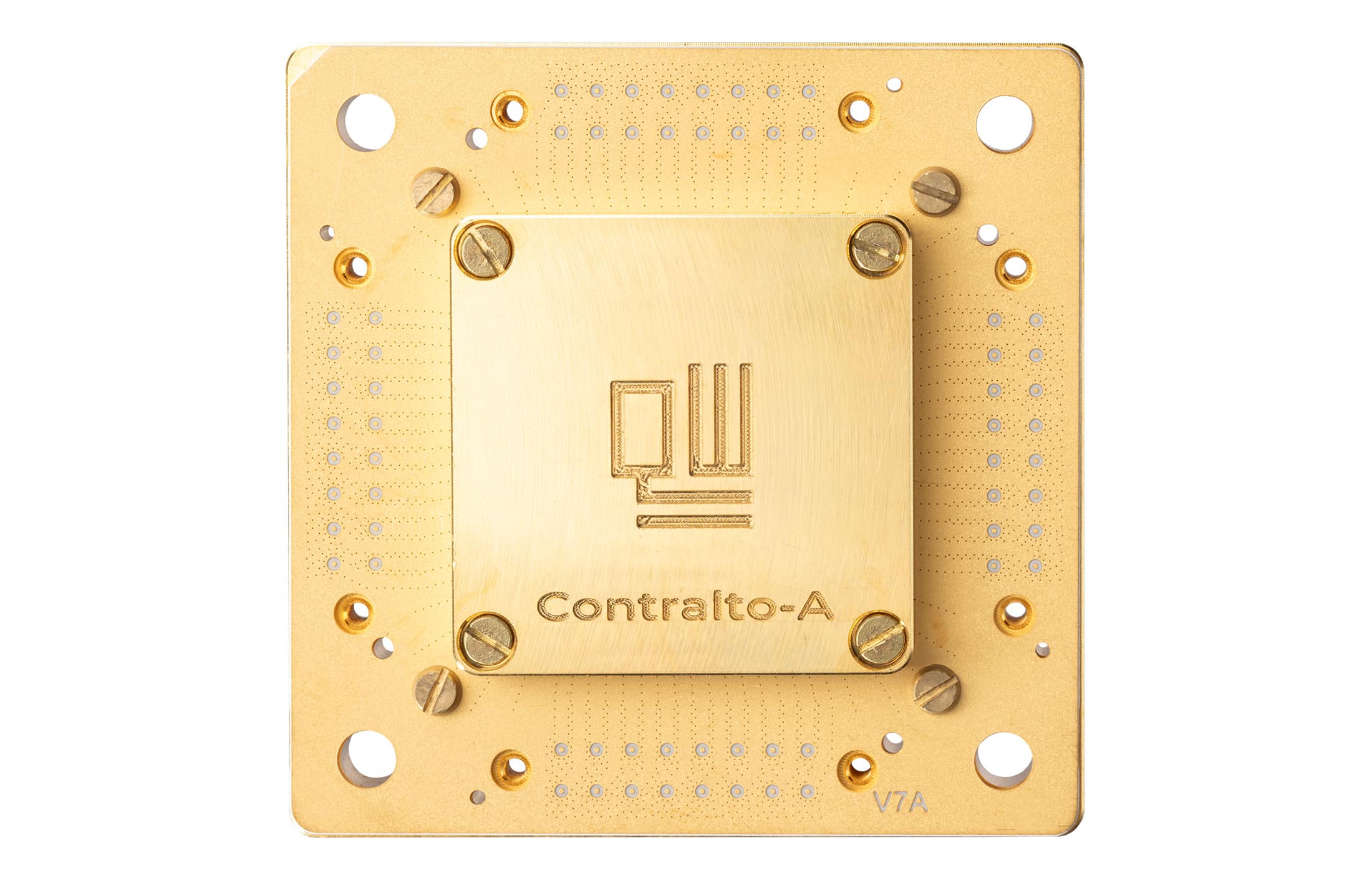

QuantWare’s own product roadmap actually gives a nuanced view that supports the “not Q Day yet” interpretation. On their website, they outline an A-Line of processors aimed at quantum error correction experiments, and a D-Line aimed at helping integrators scale up NISQ (noisy intermediate-scale quantum) systems. The milestones there are telling.

For the A-Line (QEC-focused), they start with a 17-qubit device (Contralto-A17) that is optimized for a distance-3 surface code and capable of real-time quantum error correction experiments. That is shipping now. Next on the roadmap is a 41-qubit chip (Tenor-A41) in 2026, intended for achieving logical operations (like demonstrating a logical two-qubit gate). Then a 250-qubit device (Baritone-A250) in 2027 for running small logical circuits and deeper QEC routines. Only after those stepping stones comes the 10k-qubit processor in 2028 (Bass-A10K), which they describe as enabling “quantum algorithms” – i.e., tackling the first useful problems out of reach of today’s machines. They even phrase it as “solving the first wave of problems that were previously out of reach for humanity” – clearly aspirational, attached to the 2028 device. But the key point is: they themselves are acknowledging a stepwise path. First get error correction working on small codes (17 qubits). Then scale it up slightly and do logical gates (41). Then bigger for logical circuits (250). Then go for algorithms with 10k.

Their D-Line (NISQ/integration-focused) similarly goes from a tiny 5-qubit “Soprano-D5” (entry point for new system builders) to a 21-qubit (Contralto-D21) currently, then a 64-qubit in 2027, a 450-qubit in 2028, and a projected 18,000-qubit “Bass-D18K” system in 2028 for large-scale NISQ applications. The D-Line emphasizes “footprint efficiency” and cost-effective scaling – meaning it’s for people who want to build bigger quantum systems without necessarily doing full error correction. Again, it tops out with a huge number (18k qubits) in 2028, but framed in terms of NISQ and integration, not “we solved computing”.

This roadmap structure quietly underscores what insiders know: the meaningful milestones are not just “more qubits,” but hitting certain functional targets – real-time QEC, then logical qubits, then logical gates, then logical circuits, and only then full-blown algorithms. QuantWare’s roadmap basically mirrors those stages, with specific qubit counts attached. And notably, even that final 10k device in 2028 is presented as the beginning of solving new problems, not as “we have solved quantum computing.”

So yes, QuantWare’s external messaging in the press release was ambitious and very forward-looking. But their internal roadmap and website messaging is also a reminder that the industry is painfully aware of the multi-stage journey from physical qubits to fault-tolerant computing. The 10,000-qubit goal is just one (albeit big) milestone on that journey, not the end of it.

Research Pedigree vs. Real-World Execution

One way I like to evaluate credibility of announcements is to use published papers as a proxy. And I think the best signal here is to look at CTO Alessandro Bruno’s academic contributions from his time at QuTech. Indeed, Bruno appears as a co-author on several notable superconducting QEC papers:

- A 2015 Nature Communications paper (Ristè et al.) demonstrating stabilizer-based error detection for bit-flip errors in a logical qubit encoding. In that experiment, they used a 5-qubit superconducting device to repeatedly measure parity-check operators (stabilizers) of a simple 3-qubit repetition code, catching bit-flips on the fly without destroying the encoded information. This was an early demonstration of a key ingredient of QEC: using ancilla qubits to detect errors in real time.

- A 2017 Phys. Rev. Applied paper (Versluis et al.) presenting a scalable circuit and control scheme for the surface code. They proposed a specific unit cell architecture for a monolithic surface-code lattice of transmon qubits, including a scheme to pipeline operations and avoid frequency collisions as the lattice grows. Essentially, it was an engineering blueprint for how you could layout and control a large patch of surface code, with repetition in space (unit cells) and in time (pipelined error correction cycles).

These aren’t papers that say “we solved quantum error correction,” but they are exactly the kind of work you’d want a team to have experience with if they’re attempting to build a 10,000-qubit device. It shows Bruno and colleagues have been wrestling for years with how to measure stabilizers without blowing everything up, and how to architect control systems that could scale to large grids of qubits. In other words, the technical leadership has serious research DNA in the right problems – not just qubit physics, but also the dirty work of running an error-correcting code in hardware.

At the same time, this is where being “ahead” becomes slippery. Many leading quantum teams (IBM, Google, academic consortia) have deep QEC pedigrees too. Having published papers on stabilizer measurement or surface code layouts is almost table stakes at this point for contenders in the fault-tolerance race. What will separate the winners is not who can write or explain those concepts – it’s who can execute them in a large, reliable system. That’s why I find QuantWare’s emphasis on things like packaging, chip yields, and an in-house fab actually more relevant to their differentiation than any single academic paper. It signals they understand that to win, you have to solve not only the theoretical QEC challenges but also the mundane manufacturing and integration challenges.

In summary, QuantWare’s team has a credible background and they’re focusing on often-overlooked engineering problems. That’s a good sign. But the same could be said of other top teams – so it will come down to who delivers results in hardware over the next few years.

Crypto Risk Outlook: Momentum, Not Immediate Danger

Now, stepping back to the cybersecurity viewpoint: What does QuantWare’s announcement mean for forecasting quantum risks to encryption? In my CRQC (Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computer) framework, I map any such news onto two axes: foundational capability improvements vs. actual cryptanalytic capability.

VIO-40K (if it works) is primarily a boost to the foundational layer of quantum hardware. It potentially removes or mitigates a key engineering bottleneck (the I/O and packaging problem) that could have slowed down scaling. This is very important for the long term, because a full cryptanalysis-capable quantum computer will require solving all the bottlenecks – not just qubit coherence and gate fidelity, but also system size, wiring, modularity, etc. A good analogy is the development of classical supercomputers: it’s not just about CPU clock speed, but also about architectures that allow many CPUs to work together, memory bandwidth, cooling, etc. VIO-40K is addressing one of those “boring” but necessary pieces for quantum. If such solutions pan out, it means the field can scale hardware faster and with more confidence. That could, in turn, bring forward the dates at which certain milestones (like demonstrating a logical qubit, or running a small error-corrected algorithm) occur. In other words, it increases the plausibility and maybe the speed of reaching the next scaling milestones.

However, VIO-40K does not directly move the needle on the core CRQC question (breaking RSA) unless it’s accompanied by progress on all the other fronts that turn a large noisy device into a useful one. By itself, a 10k physical qubit device with standard ~1% two-qubit error rates is not breaking any encryption; it’s just a bigger noisy device. To be crypto-relevant, it would need to come with evidence of, say, error rates below threshold (e.g. 0.1% or better gates), a functioning error correction scheme, scalable syndrome extraction (measurements of error syndromes across the whole chip), real-time decoding (probably using something like NVQLink-connected GPUs to handle the error correction decoding algorithms), and the ability to run stably for long periods. Those are the capabilities that convert physical qubits into logical qubits, and convert “logical qubits exist” into “logical qubits can run deep circuits without crashing.”

Even if we grant QuantWare every benefit of the doubt about hitting their targets, the scale described (10k physical qubits) is still far from the “attack machine” scale implied by the best-known public estimates. Recall Gidney’s <1 million noisy qubit estimate for RSA-2048 factoring. We’re talking about needing two orders of magnitude more qubits, plus all the error correction overhead. And that estimate already assumed pretty optimistic error rates (0.1%) and speeds (1 µs cycle). If those aren’t met, the qubit count required goes up further. So, 10,000 qubits is simply not in the same ballpark as what’s required for breaking modern cryptography. It’s progress, but it’s not a solution to Shor’s algorithm’s shopping list.

So, my net view for security professionals is: this announcement is a positive sign that the industry is tackling the right scaling issues, and it might accelerate the timeline to large-scale quantum hardware, but it does not shorten the cryptographic threat timeline to “now.” It doesn’t make me change my estimates for when CRQCs might appear; it just adds confidence that we are systematically working through obstacles on the way there.

What to Watch Next

If QuantWare (or the industry in general) wants to turn big physical qubit counts into something cryptographically relevant, a few important steps will need to happen in the coming years. Here’s what I’ll be watching for next:

- Demonstrations of low error rates at scale: For VIO-40K to be truly useful, we’d want to see that adding all those chiplets and I/O lines hasn’t introduced unmanageable noise. A great sign would be a medium-scale test (maybe a few hundred qubits) showing error rates still at or below the threshold needed for error correction (perhaps <1% two-qubit gate error, ideally ~0.1% in the long run). If they can show, say, a 100-qubit patch of their architecture running with errors comparable to the best 2D chips, that would validate the 3D approach’s viability.

- A physical-to-logical qubit roadmap (with data): It would be reassuring to see QuantWare (or partners) publish a clear mapping like: “with X physical qubits at Y error rate, using surface code of distance d, we project a logical error rate of Z.” In other words, some transparency about how those 10,000 qubits could be used for error correction. Right now, “10k qubits” is just a raw count. I’d love to see something like: if each chiplet has, say, 1000 physical qubits with 0.1% error, you could encode maybe ~10 logical qubits of distance ~25 (rough number) across the whole device, etc. It doesn’t have to be exact, but a sketch of how the architecture translates to logical capacity would separate realistic planning from pure hype.

- Chip-to-chip link fidelity: The whole concept of stitching chiplets together relies on those inter-chip connections being as good as internal connections. QuantWare called them “ultra-high-fidelity,” but we need numbers. Are they 99.9% fidelity CZ gates between chiplets? 99.99%? And what’s the communication latency between chiplets? If, for instance, two qubits on different chiplets have a slower or noisier interaction, that could bottleneck certain operations or make some error correction cycles fail. I’ll be watching for any disclosure or experiment about the fidelity of operations that cross chip boundaries. Weak links in a chain can spoil the whole chain’s strength.

- Operational stability and automation: As noted, 40k I/O lines implies a lot of classical control. I’ll be interested in whether QuantWare partners with control system experts (like Qblox, Quantum Machines, Q-CTRL, etc.) to demonstrate they can automate calibration and feedback for such a complex system. In a fault-tolerant quantum computer, you might have to adjust qubit frequencies, pulse shapes, etc., on the fly as conditions drift. Doing that for thousands of qubits is a big ask. If, say, by 2027 QuantWare and collaborators show a smaller VIO-based system that can run for hours with automated calibration, that would be a strong indicator that a 10k system could be managed.

In essence, to move this from “a big number headline” to “evidence for CRQC timeline changes,” we need to see system-level proofs: that the qubits can be kept in line, that error correction can actually happen across them, and that the whole thing can run continuously like an industrial machine, not just a flash experiment.

The Bottom Line

When colleagues or clients see the “10,000 qubit” news and ask me, “So, is Q Day here?”, the message I send back is roughly this:

A 10,000-qubit announcement is meaningful progress on scaling the physical hardware – especially in tackling wiring and packaging bottlenecks – but breaking cryptography depends on logical qubits and sustained fault-tolerant operation. QuantWare’s first VIO-40K devices won’t even ship until 2028, and even then, the best current public estimates (e.g. Gidney’s work) suggest you’d need on the order of a million qubits with error correction to factor RSA-2048. So this is a great signal of momentum in quantum engineering – not the arrival of a cryptanalytically relevant machine. It’s not downplaying QuantWare’s achievement; it’s just putting the news into the frame that matters for security: capability, not just headcount.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.