Chokepoints and Industrial Base Realism: What “Quantum Supply Chain Sovereignty” Actually Means

Table of Contents

Introduction: From Rhetoric to Bill-of-Materials Reality

Talk of quantum sovereignty – a nation’s independent control over quantum technology – means little unless backed by tangible supply chain control. Quantum innovation relies on narrow, specialized supply chains that are globally dispersed and often fragile. Major powers have realized this and are pivoting from pure research funding to securing the physical and human infrastructure for a quantum industry. The objective is to ensure that specialized tools of production – from cryogenic refrigeration systems to precision photonic components – remain under trusted domestic or allied control. In practice, this means scrutinizing every item on the quantum computing “bill of materials” and asking: who makes this, and could we get it if geopolitics turn sour?

Achieving sovereignty does not imply total self-sufficiency (autarky). Instead, experts emphasize a blend of sovereignty and optionality. The goal isn’t to cover the entire quantum stack alone, but to ensure core strategic pieces can be produced or procured on your own terms.

In other words, nations seek selective self-reliance for critical components and multiple options for everything else. By investing in key domestic capabilities while diversifying partnerships, countries aim to have a “minimum viable” quantum toolkit under sovereign control.

Mapping the Quantum Industrial Base Stack

To make sovereignty concrete, we must map out the quantum computing industrial base from bottom to top. This stack includes all the enabling technologies, facilities, and skills required to build and operate quantum computers. Below are the key layers and components:

Enabling Components

The specialized parts that quantum hardware depends on. These include high-performance lasers and optics (for ion trap and photonics-based qubits), microwave sources and amplifiers, ultrastable power supplies, high-vacuum and cryogenic parts, and high-purity materials.

For example, trapped-ion and neutral-atom systems require multiple frequency-locked lasers and precision optics, while superconducting qubits need ultra-low-noise microwave cabling and amplifiers. Many of these components come from niche suppliers – e.g. Toptica and Coherent for lasers, or Low Noise Factory for cryogenic amplifiers – often concentrated in certain countries.

Without these enabling pieces, advanced qubit experiments simply cannot be realized.

Fabrication Capabilities

The manufacturing infrastructure to produce quantum devices. Quantum chips (whether superconducting circuits, semiconducting spin qubits, photonic integrated circuits, etc.) rely on semiconductor-grade fabrication facilities. This means access to cleanrooms, lithography systems, etching and deposition tools, and materials processing at nanometer precision. Only a few labs or foundries worldwide can fabricate high-quality qubit chips, and they often depend on the broader semiconductor supply chain (e.g. lithography equipment from ASML, specialty chemicals, silicon wafers).

A nation’s sovereignty in quantum is limited if it lacks domestic chip fabrication for qubits or at least secure access to an allied foundry. Even supporting technologies like superconducting cables or MEMS mirrors require precision manufacturing capabilities.

In short, quantum computing is entangled with semiconductor and precision manufacturing – any weakness in those domains affects quantum.

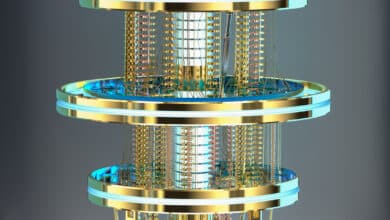

Cryogenics & Control Systems

The hardware to operate qubits at extreme conditions. Many quantum processors (superconducting, spin, some photonic) must run at millikelvin temperatures, demanding dilution refrigerators and cryostats. Just a few companies globally produce these ultra-cold refrigeration units (notably Bluefors in Finland and Oxford Instruments in the UK), and lead times can be many months.

Alongside cryogenics, sophisticated control electronics are needed to interface with qubits – for example, microwave signal generators, arbitrary waveform generators, fast digitizers, FPGAs, and specialized RF signal routing to qubits. Key suppliers here include firms like Keysight Technologies, Zurich Instruments, and emerging quantum-specific vendors (e.g. Qblox for modular control hardware). These control systems often must themselves operate in cryogenic conditions or at least be engineered for low noise and latency.

In sum, without cutting-edge cryogenic cooling and control apparatus, quantum computers would remain theoretical – they are the workhorses that translate digital commands into precise physical manipulations of qubits.

Packaging and Integration

The engineering that integrates qubit chips and components into a functional machine. Quantum chip packaging is far more complex than packaging a classical semiconductor. Qubit devices often require wire-bonding or flip-chip mounting onto circuit boards that fit inside cryostats or vacuum chambers, with dozens of microwave/RF lines or optical fibers going in and out. Maintaining signal integrity and thermal isolation is critical – for instance, superconducting qubit chips are mounted on multilayer microwave packages with cold filters on each line, and photonic qubits may be aligned with fiber arrays and nonlinear crystals inside temperature-stabilized housings.

This packaging work is typically custom and high-precision, involving specialized techniques (e.g. superconducting bump-bonding, photonic fiber coupling) that only a few groups have mastered. Robust cryogenic packaging has become a strategic focus for quantum hardware firms because poor packaging limits scale-up and reliability.

Sovereignty here might mean having domestic labs or companies capable of packaging qubit devices and assembling cryogenic systems, rather than relying entirely on foreign engineering services.

Firmware & Software Toolchains

The low-level software that makes quantum hardware usable. This includes the firmware embedded in control hardware (or FPGAs) that orchestrates pulses to qubits, as well as the software drivers, compilers, and calibration routines that sit between the quantum algorithms and the physical qubits. Examples range from pulse-sequencing software (like the QUA language by Quantum Machines or Q-CTRL’s feedback control tools) to qubit calibration routines (e.g. Qblox and Quantum Machines provide software to auto-calibrate gates).

While software is more easily distributed than hardware, it’s still a part of the supply chain – if all calibration software expertise resides in one foreign vendor, a country might be stuck if that vendor withdraws support. Open-source frameworks (like Qiskit, Cirq, or Q-CTRL’s open tools) help reduce this risk.

Nonetheless, building a domestic knowledge base in quantum firmware and control software is often a goal for sovereignty, ensuring local teams can maintain and adapt the systems. This layer blurs into the higher software stack (algorithms, applications), but is included in “industrial base” because it directly affects hardware functionality and requires specialized skills bridging software and experimental physics.

Metrology & Test Infrastructure

The instruments and expertise to measure, calibrate, and verify quantum devices. Quantum hardware must be characterized at each step – from verifying qubit fabrication (e.g. measuring Josephson junction resistance on a chip) to continuous calibration of qubit performance (gate fidelities, coherence times) during operation. This demands a suite of advanced test equipment: cryogenic probe stations (for on-wafer testing at low temperatures), high-speed oscilloscopes and vector network analyzers, single-photon detectors for optical systems, atomic force microscopes for inspecting qubit surfaces, and so on.

Equally important is the metrology know-how to obtain reliable measurements at the quantum level. National metrology institutes and standards (for timing, microwave power, photon detection efficiency, etc.) play a role in providing reference calibrations. A country lacking this infrastructure will struggle to trust the performance of its quantum devices without outside assistance.

In essence, metrology is the quality-control backbone of the quantum supply chain – as crucial to sovereignty as the factories, since owning a quantum fab or computer means little if you cannot verify its output or diagnose problems.

Service and Operations

Finally, the capability to deploy, maintain, and use quantum computers as a sustained service. Current quantum systems require highly specialized operation: cryostats need constant monitoring, qubits need frequent recalibration, and software stacks need updates as algorithms improve. Many end-users access quantum computers through cloud services (e.g. IBM Quantum via the cloud, Amazon Braket) rather than owning the machine.

From a sovereignty standpoint, however, relying solely on foreign cloud providers could be a risk (e.g. access could be revoked or data could be subject to foreign jurisdiction). Thus, an element of quantum sovereignty is the ability to host quantum computing facilities or at least have on-premises quantum systems under domestic control.

For example, Germany negotiated to host an IBM quantum computer on German soil with local researchers operating it – gaining experience and assurance of access even though the machine was IBM-built. Operating a quantum data center also means having technicians and engineers who can keep the system running (e.g. managing cryogen supply, replacing components, troubleshooting errors). This operational know-how is part of the supply chain of talent and processes.

Moreover, quantum service infrastructure extends to things like secure facilities (since quantum devices might be considered critical national labs), classical co-processing capabilities (to feed and read out the quantum system), and supply of expendables (like cryogens or replacement parts).

A sovereign stance would push for at least one quantum computing center domestically (perhaps at a national lab or large company), even if built with international partners, to ensure hands-on mastery of the technology.

This quantum industrial base map shows the wide range of dependencies – from raw materials and chips to software and people. Next, we identify which of these dependencies function as chokepoints: critical links that are hard to substitute, concentrated in supply, or under external control.

Chokepoints and Critical Dependencies in the Quantum Supply Chain

Not all parts of the quantum stack are equally vulnerable. Some have healthy global markets or multiple alternatives; others are dominated by a single supplier or country, or inherently scarce. Quantum supply chain chokepoints are those dependencies that, if cut off, could stall an entire program. Here are several of the most significant ones:

Ultra-Cold Refrigeration

The dilution refrigerator is often cited as a single-point-of-failure in quantum computing development. Only a handful of companies manufacture dilution fridges capable of reaching the millikelvin temperatures needed for superconducting and some semiconducting qubits – notably Bluefors and Oxford Instruments as market leaders. This concentration means long lead times (often over 6-12 months for a new fridge) and vulnerability to export restrictions.

If, for instance, a country was sanctioned from buying these, internal quantum R&D would come to a standstill. There are no easy substitutes for a dilution fridge; alternative cooling tech (like ADRs or cryocoolers) cannot reach the same ultra-low temperatures at scale.

This chokepoint has already been observed: multi-month backlogs and reliance on a small supplier base for dilution refrigerators have constrained quantum labs.

Any sovereignty strategy must address cryogenics – either by developing domestic manufacturing capacity, or by strong alliances with the producing nations.

Specialized Raw Materials

Several materials critical to quantum hardware are scarce, have few suppliers, or are subject to geopolitical risk. A prime example is helium – especially Helium-3, used in certain cryogenic systems – which is extremely rare (a byproduct of nuclear decay) and in limited supply. Even Helium-4 shortages in recent years have impacted cryogenics-dependent research.

Other examples include isotopically enriched Silicon-28 (vital for silicon spin qubits because it has zero nuclear spin; only a couple of facilities in the world produce Si-28 in quantity), high-purity superconducting metals like Niobium and Indium for qubit fabrication (mined in only a few countries, with China a major source of Indium), and thin-film lithium niobate (LiNbO₃) for optical quantum chips (a material where supply could bottleneck photonics). These have minimal or no substitutes; if you can’t get LiNbO₃ waveguide substrates or if isotopically pure silicon is unavailable, you simply cannot achieve the required qubit performance.

Such materials are candidates for stockpiling or onshoring because losing access would directly choke off progress. Recent trade moves highlight the risk: for instance, export curbs on semiconductor-related elements like gallium and germanium (used in some quantum photodetectors and chips) show how strategic dependencies can be weaponized.

Precision Lasers & Photonic Components

Many quantum modalities (trapped ions, neutral atoms, some sensors and communication systems) rely on laser systems and photonic devices that are highly specialized. Examples include narrow-linewidth lasers at uncommon wavelengths (often produced by only a few companies globally), single-photon sources and detectors (e.g. superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors, where companies like ID Quantique or Single Quantum lead), and nonlinear optical crystals or modulators for quantum light manipulation. These components form a chokepoint because the market is small and cutting-edge: a slight disruption in a single supplier could leave few alternatives.

High-end scientific laser firms are mostly located in the US, Europe, or Japan, making other countries dependent on imports. Some laser tech is dual-use (precision lasers can be used in military systems), hence subject to export controls. Photonics and laser supply chains are a sovereignty concern – the UK, for example, identified partnering with Germany (home to leading laser/photonics firms) as crucial to secure these inputs.

In practice, ensuring optionality here might mean qualifying multiple suppliers (where possible) for each needed optical component, and investing in domestic photonics startups to build capacity. But given the high expertise required, this remains an area where many nations will lean on a few trusted exporters.

Quantum-Classical Control Electronics

Every quantum computer depends on a suite of classical electronics to control and read out qubits. While these draw on the broader electronics industry, there are choke points at the performance frontier. For instance, superconducting qubit systems need extremely low-noise, high-bandwidth microwave electronics – a domain dominated by a few firms (Keysight in the US, Rohde & Schwarz in Germany, etc.) Similarly, high-speed analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) and digital-to-analog converters (DACs) used in control systems are often cutting-edge chips not widely available. If a country is cut off from advanced semiconductor imports, its ability to build viable quantum control systems could be impaired.

Another emerging dependency is cryogenic electronics: as qubit counts grow, there’s a push to develop cryo-CMOS control chips that sit inside the fridge (to reduce wiring bottlenecks). Today, only a few groups (in the US, EU) have that capability, often leveraging 22nm or 14nm node fab processes – again tying back to access to leading-edge fabs. Thus, the control stack inherits chokepoints from the semiconductor industry.

Mitigating this might involve maintaining a domestic supply of general electronics (FPGA boards, etc.) and developing relationships with multiple vendors for test equipment. The latency and noise performance requirements also mean one can’t simply substitute with low-end gear without degrading quantum operation. Control electronics are somewhat more flexible than, say, cryogenics (since many components are off-the-shelf), but the highest-performance instruments remain a strategic dependency that nations track closely.

Manufacturing Equipment & Facilities

A less obvious but crucial chokepoint is the equipment needed to manufacture quantum hardware – much of which overlaps with semiconductor manufacturing tools. If you need to fabricate a superconducting qubit chip, you require deposition tools for superconducting films, high-resolution lithography (e.g. electron-beam writers for defining Josephson junctions or quantum dots), and etching tools. The most advanced of these tools (like EUV lithography machines, or even specialized etchers for deep silicon etch) are produced by very few companies globally (e.g. ASML, Applied Materials, Lam Research). Countries lacking those toolmakers must import them, often under export license. This can become a chokepoint if exports are restricted. Even something like a high-precision wirebonder or wafer-bonding machine for assembling quantum chip packages could be a bottleneck if only a single foreign supplier exists. Precision metrology equipment (like scanning electron microscopes, quantum analyzers, etc.) also falls here – without it, yields and quality control suffer.

Essentially, quantum R&D and production require the whole ecosystem of semiconductor equipment, and no single nation (except perhaps a very few) is entirely self-sufficient in that. This is why quantum programs are often entangled with broader semiconductor policy – e.g. the US CHIPS Act and related measures explicitly include quantum-related fabrication in their scope.

Sovereignty plans must honestly account for these upstream dependencies; sometimes the solution will be to piggyback on allied semiconductor supply chains rather than duplicating them.

Human Talent and Know-How

Perhaps the most fundamental choke point is the talent pipeline. Quantum science and engineering expertise is in short supply worldwide. Only a limited number of experts know how to design a qubit chip, operate a dilution fridge, or calibrate a 100-qubit system. This makes skilled people a strategic resource that nations compete over. If your country’s quantum program relies on foreign experts at key positions, that’s a vulnerability – those people could leave or be pulled back home. Recognizing this, governments are treating workforce development as critical: the UK and EU are expanding postgraduate programs and trying to retain talent, and the U.S. has education partnerships to train quantum engineers from a young age. Talent can even be weaponized in a sense – with concerns about “brain drain” or adversaries recruiting away your top scientists.

In sovereignty terms, a country needs a domestic knowledge base sufficient to absorb and advance the technology. That means training quantum PhDs, upskilling traditional engineers in quantum hardware, and fostering a community that can carry on if external support is cut. Unlike a part you can stockpile, people can’t be stockpiled – they must be continually nurtured. Many consider this the ultimate bottleneck in quantum tech: without a skilled, security-cleared workforce, even a fully built quantum system cannot be sustained.

These chokepoints illustrate why quantum supply chain discussions are front and center in strategic tech planning. They also show quantum’s overlap with other critical industries: a vulnerability in the helium supply, or in high-end chips, directly impacts quantum progress. Moreover, quantum tech’s dual-use nature (civilian and military) means chokepoints can quickly become national security issues, subject to export controls and sanctions.

For instance, both the EU and UK have added certain quantum technologies and equipment to their controlled export lists, and the U.S. has imposed restrictions on quantum computing exports to geopolitical rivals.

In short, a nation cannot be sovereign in quantum if any single chokepoint can be used as leverage against it. This reality is driving a re-think of what “tech sovereignty” means in the quantum era, as discussed next.

Why Quantum Sovereignty Differs from Digital Sovereignty

Quantum supply chains underscore that sovereignty in quantum is a far more physical challenge than in typical digital tech. In the past, discussions of “digital sovereignty” often revolved around data residency, control over software, or maybe domestic semiconductor design. But quantum computing brings a “stubborn physicality” back into the equation – akin to the aerospace or energy industries. There are several key ways in which quantum sovereignty diverges from the usual digital paradigm:

Hardware-Centric and Hands-On

Unlike cloud computing or software services that can be provisioned globally with little friction, quantum computing requires direct access to custom hardware that cannot be easily duplicated. You can’t download a dilution fridge or 3D-print a qubit chip overnight. This means countries must focus on hard infrastructure (labs, fabs, cryo facilities) in a way that goes beyond digital infrastructure.

The importance of physical location and ownership is higher – e.g. having a quantum machine on your soil under your control is qualitatively different from just using a foreign cloud service. In classical tech, one might argue it doesn’t matter where a server is as long as you have access; in quantum, where a device is built and operated does matter (for both security and practical reasons).

Entwined with Semiconductor Supply Chains

As noted, quantum tech is deeply entwined with the semiconductor and precision manufacturing ecosystem. This is a departure from many digital technologies where the infrastructure (like commodity CPUs, PCs, networks) is mature and globally traded at scale.

Quantum, by contrast, leans on cutting-edge manufacturing processes that are already chokepoints even for classical computing (e.g. access to latest lithography). So quantum sovereignty is partially an extension of semiconductor sovereignty – a topic well understood to involve heavy capital investment, long lead times, and international dependencies. A country that felt comfortable simply buying all its classical chips might find that strategy unviable for quantum components, which are not mass-produced commodities but often bespoke.

In essence, quantum sovereignty forces nations to confront high-tech manufacturing sovereignty head-on, whereas digital sovereignty debates could sometimes sidestep that by focusing on software.

Ongoing Calibration & Maintenance Needs

Quantum devices are analog, noisy, and require continual calibration – far more so than classical IT equipment. This means the operational dependence doesn’t end at purchase; whoever supplied the system or its key components might be continually involved in its upkeep (through software updates, calibration support, replacement parts, etc.). Sovereignty therefore demands having domestic capability in metrology and maintenance. In classical terms, it’s as if owning a supercomputer also required you to have in-country experts to re-tune the CPU every week – a much more intimate reliance.

Quantum sovereignty implies building an ecosystem of local expertise that can independently run and service the technology, not just buy it. For example, if a timing reference in a quantum system drifts, do you have a national metrology lab that can recalibrate it, or must you ship it back to the manufacturer abroad? These nitty-gritty questions differentiate quantum from a typical “set it and forget it” IT stack.

Smaller Scale, Greater Fragility

Today’s quantum industry is nascent – the supply chain is small and not yet resilient. In classical digital tech, we benefit from huge economies of scale and many interchangeable suppliers for most components. Quantum has not reached that level of commoditization. The relative fragility (as evidenced by helium shortages or single-source components) means sovereignty is more precarious. A single factory’s output (for example, a company making a specialized quantum sensor) might be the lifeline for dozens of global projects. This reality makes governments uncomfortable depending purely on market forces. It also means the loss of one partnership or supplier can have outsized impact, whereas in mature industries there’s usually another vendor around the corner.

Thus, quantum sovereignty emphasizes resilience and backup plans from the start, rather than assuming open markets will provide.

Talent as a Strategic Asset

In digital tech, talent is important, but code can be copied and run anywhere if you have it. In quantum, the tacit knowledge residing in experts is crucial – and not easily transferable or replaceable. As mentioned, quantum sovereignty elevates human capital to a first-class concern: training and retaining people who understand this complex tech is as important as the hardware itself. This aligns with how nations treat defense or nuclear tech talent.

It’s a departure from typical IT sovereignty where often the worry is just having domestic companies or control of data, rather than whether your pool of scientists is sufficient. Quantum forces a melding of industrial policy with education and immigration policy (to attract talent). We see countries establishing whole quantum training programs and even treating top scientists almost like strategic resources to guard.

In short, the “supply chain” in quantum includes people and knowledge networks, not just hardware, to a degree not seen in many other tech domains.

National Security Overlay

Because a fully capable quantum computer poses potential strategic threats (e.g. to encryption) and advantages (to intelligence, economic power), quantum tech is being viewed through a national security lens much sooner than most emerging technologies. This leads to things like export controls, security classifications, and alliance-based development happening early. Digital sovereignty debates (e.g. about 5G or cloud) have national security elements too, but quantum’s dual-use nature means almost every piece of the supply chain could be seen as sensitive. A high-end cryostat or a special laser might be treated like defense articles.

Sovereignty in this context isn’t just about economic advantage, but about who one trusts to be part of your supply chain. We are already seeing blocs form (U.S./Europe/Japan alliances versus more restricted tech transfer to China, for example). This differs from, say, general IT hardware where until recently a country might freely buy servers or chips from anywhere. With quantum, nations are proactively building “trusted supplier” networks and excluding others for security reasons. That reinforces sovereignty efforts but also complicates the global market – potentially increasing costs and fragmenting the supply chain by geopolitical zone.

In summary, quantum sovereignty demands a material, ground-truth approach: it’s about vacuum chambers and microwave cables as much as about algorithms and data. It marries high-tech manufacturing concerns with cutting-edge science and security policy. Nations can’t treat quantum tech like just another software platform; they must treat it like an emergent critical infrastructure – one that requires hands-on control over atoms and devices, not just bits and bytes.

Building a “Quantum Dependency Heatmap” for Sovereignty Planning

How can countries or organizations translate the above insights into a practical strategy? One useful exercise is to create a dependency heatmap of the quantum supply chain. This means mapping each layer and component (as outlined in the industrial base stack) against the availability and control of its supply, then marking where the risks are highest. Such a heatmap visually highlights where sovereignty “hotspots” exist – the points at which lack of domestic capability or limited suppliers create vulnerability.

To construct a quantum supply chain heatmap, consider the following steps:

- List Key Supply Categories: Enumerate all critical inputs and capabilities (materials, components, tools, skills) required for your quantum program. Use the stack layers (components, fabrication, cryo, etc.) as a guide. Be specific – e.g. “Dilution refrigerator at 10 mK”, “Laser at 729 nm for ion qubits”, “High-vacuum pump”, “Qubit chip fab process at 22nm”, “Microwave AWG at 5 GS/s”, “Quantum control software stack”, “Cryogenic RF filter”, “Quantum algorithm experts”, etc.

- Identify Current Sources: For each item, note where it currently comes from. Is there a domestic source, and if so, is it robust (commercial or just in-lab)? If no domestic source, which country or company is providing it? Are there multiple suppliers globally or just one? This step essentially catalogs the origin of each element in your quantum efforts.

- Assess Substitutability & Concentration: Mark items that are hard to substitute. A red flag might be: “Only one known supplier worldwide” or “Only produced in Country X”. Also mark if an item is subject to export controls or extreme scarcity. For example, if your list includes “Helium-3 gas” or “EUV lithography machine,” these would be highlighted as very high-risk dependencies (few sources, high barriers). On the other hand, something like “standard electronic resistors” might be green (widely available, many suppliers).

- Rate Each Dependency: Assign a color or score based on risk. Green could mean “secure or easily substitutable” (e.g. multiple friendly countries supply it, or you have a local provider). Yellow might mean “some risk” (limited suppliers or intermediate difficulty to replace). Red means “chokepoint/high risk” (single supplier or country, no easy substitute, or critical with long lead time). For instance, your heatmap may show cryogenic equipment as red (due to few vendors), certain photonic components as yellow (few vendors but maybe some alternates), and software tools as green (open-source alternatives exist, talent can develop if needed).

- Analyze Clusters of Risk: Look for patterns. You might find, for example, that nearly all red items are in the fabrication and cryogenics categories. That suggests a need to focus sovereignty measures there. Or perhaps a cluster of yellow in photonics indicates an area to nurture more suppliers or stockpile parts. This step turns the heatmap into a guide for action – the “hottest” areas demand the most attention.

Once the dependency heatmap is drawn, it becomes clearer where to apply two key strategies: developing domestic capacity and forging alliances/alternatives. The heatmap essentially asks, “if this foreign supply was cut off, do we have a fallback?” If the answer is no (red zone), then you need to create one – either by building it domestically or securing an alliance with someone who can supply it.

Minimum Viable Domestic Capabilities

The concept of “minimum viable” domestic capability emerges naturally from this analysis. Instead of trying to localize everything (which is impractical and costly), focus on reducing the red zones to yellow or green by establishing at least a minimal domestic foothold in those areas. For example:

- If dilution refrigerators are a red dependency, a minimum viable capability might be to train a domestic team in cryogenic engineering, perhaps even license technology or build a simpler homegrown fridge (even if not as advanced as Bluefors’ latest). The EU and UK have started funding indigenous projects for cryogenic equipment for exactly this reason. The goal is that, in a pinch, you have some local know-how to maintain or even fabricate cryogenic systems, so you’re not completely stranded.

- If quantum chip fabrication is a red zone (e.g. relying on a foreign foundry), minimum capability could mean setting up a quantum prototyping fab or foundry partnership at home. This might be a smaller facility that can do, say, 90 nm node superconducting circuits or basic ion trap chips – not volume production, but enough to fabricate test devices and develop processes. Japan recently demonstrated a fully home-built quantum computer, showing the payoff of long-term investment in local fabs and expertise. Indigenous chip programs (like Europe’s and UK’s for quantum ASICs) aim to ensure there’s at least one domestic source of qubit chips.

- For specialty materials (helium isotopes, isotopically pure substances), minimum viable capability could involve securing a domestic supply chain or reserves. For instance, a country could choose to produce its own Si-28 in small quantities via centrifuges, or recycle and stockpile helium from industrial use. It might not cover 100% of needs, but provides a buffer. Similarly, maintaining a national stock of certain high-purity metals or purchasing equity in a foreign mine (with agreements to secure supply) can be part of the strategy.

- In photonics, if lasers are a dependency, minimum capability might mean assembling lasers domestically from components (buying optics and pump diodes but doing the integration in-country), or nurturing one domestic laser company to build capacity in the most-needed wavelength range. If single-photon detectors are the issue, perhaps establish a lab that can at least produce and test a basic SNSPD, even if most are bought from outside. This way you gain technical experience and could ramp up if imports ceased.

- With control electronics and general test gear, full self-reliance is unrealistic (you won’t reinvent oscilloscopes completely). But a minimum capability could be to develop open-source control electronics designs and firmware that could run on multiple hardware platforms. Also, ensure you have some stock or ability to procure critical chips (like maintain an inventory of required FPGAs or ADCs). Another aspect is to invest in standards and modular architectures so that if one vendor’s product is unavailable, you can swap in another’s. Pushing for standardized interfaces (for example, a common control hardware interface) internally means you’re not locked to a single vendor’s closed system, which is itself a form of sovereignty.

- Critically, develop domestic talent as a capability. Ensure your universities and companies train people in all these niche areas (cryogenic engineering, quantum IC design, photonic integration, etc.). The minimum viable talent pool might be small (a few dozen experts in each key subfield), but having even that nucleus domestically means you can grow it as needed and you can absorb technology from elsewhere more effectively. Countries are increasingly doing this by funding dedicated quantum engineering programs and by bringing in foreign quantum experts to teach or lead labs, seeding local teams.

The endgame of minimum viable capabilities is verification and fallback: you want to be able to verify foreign-supplied components (with your own test setups and expertise) and have the capacity to swap in a domestic or allied alternative if no longer able to import from the original source. It is about building a safety net, not about autarky or duplicating the whole global supply chain at home.

Alliances and Optionality over Autarky

No country – not even the largest – can realistically cover every facet of the quantum supply chain at top-notch level. The complexity is too great and the talent pools too limited for one nation to monopolize all quantum capabilities. Sovereignty, therefore, is being pursued as a “team sport” among allies rather than a lone race. We see the emergence of what might be called quantum supply chain alliances: cooperative agreements where different countries contribute their strengths and share in the output.

For instance, the UK’s quantum strategy explicitly calls for partnering with Germany on lasers/photonics, with the Netherlands on semiconductors, with Japan on materials, and with Canada on software. Each of those partners is strong in a particular slice of the stack, so the UK doesn’t need to replicate everything domestically – it can rely on a trusted partner for that piece. In return, the UK might provide expertise in, say, quantum encryption or superconducting design. The European Union similarly advocates diversifying partnerships to “reduce dependencies”, engaging with the US, Japan, Canada and others so that no single dependency becomes critical.

This approach is effectively sovereignty through optionality: by having multiple suppliers or collaborators for each critical input, you ensure that you’re never cornered. If Partner A is suddenly unavailable (due to political or supply issues), Partner B can fill in. It’s a conscious effort to avoid the mistakes of past over-reliance (for example, Europe’s past over-reliance on a single region for certain semiconductors or rare earth materials). In quantum, because it’s early, countries are trying to “design out” single points of failure via agreements. We also see initiatives like Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) promoting modular, mix-and-match designs for quantum systems. If everyone builds quantum computers in a modular way – e.g. you can plug in any compatible qubit module or any vendor’s control hardware – then nations can more easily swap components from different sources. This reduces vendor lock-in and bolsters collective resilience. A great example is a recent Italian quantum computer that combined a Dutch-made quantum processor, locally made control electronics, and a Finnish cryostat – all integrated to create a working system. By going modular, they avoided being dependent on one single country or company for the whole machine, proving the value of this strategy.

Another facet of alliances is joint investment in shared infrastructure. Alliances like AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) or EU-US partnerships are exploring sharing quantum testbeds and facilities. If one country has a specialized fabrication tool, allies might get access to it, mitigating the need for each to buy their own (expensive and redundant). Similarly, allied countries might coordinate to ensure collective capability: e.g. Country X focuses on quantum sensing, Country Y on quantum interconnects, and they trade results. This “niche specialization” approach means each nation becomes sovereign in its niche and interdependent for others, which can actually enhance group sovereignty since each one controls a piece of the puzzle. The risk (to be managed) is that the alliance must hold – but that is why these are typically done among longstanding allies with aligned interests.

In short, quantum supply chain sovereignty is not about isolation, it’s about insurance. Insurance achieved through both having some domestic production (so you’re not helpless) and through friendly diversification (so you’re not overly reliant on any single external source). The guiding question is, for every critical item: “If X supplier went away, do we have a way to continue?” If the answer is yes (because of an alternate supplier or an internal capability), then you have optionality. If the answer is no, that item needs attention.

Conclusion

Quantum technology is forcing policymakers to get realistic about what tech sovereignty means. It’s no longer an abstract notion of controlling data or owning intellectual property – it is literal control over atoms, devices, and talent. The exercise of mapping quantum’s industrial base and choke points is sobering: it reveals that lofty national goals depend on very tangible things like a supply of isotopes, a working cryostat, or a handful of skilled microwave engineers. The encouraging news is that this reality check is happening early. Countries and coalitions are already acting on the “dependency heatmaps” implicitly – investing in critical components, forming partnerships for others, and planning for supply chain shocks.

The outcome we can expect is a more materially grounded approach to sovereignty. We’ll likely see “quantum dependency reviews” become as routine as financial audits for major programs, and the rise of public-private efforts to fortify each vulnerable link (whether through funding a local company or striking a deal with an ally). Sovereignty in quantum will be measured not by slogans but by checklists: Do we have access to this tool? Can we make that component? Is there an alternate source for this material? Are our people trained to do X if partner Y cannot? The nations (and industries) that excel in quantum will be those who can answer these questions confidently.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.