Quantum Sovereignty in Practice: When Geopolitics Becomes Architecture

Table of Contents

Part of Series: Quantum Sovereignty & the New Cold War (Part 4 of 6)

This article picks up where "Physics at the Heart of the New Cold War" left off. That piece looked at how deep physics is turning into geopolitical leverage; this one focuses on the operational response - how nations and strategic industries translate that reality into sovereignty strategy: supply chains, standards, talent, and control of critical infrastructure. And for a macro map of the quantum race, see Quantum Geopolitics: The Global Race for Quantum Computing. For an introduction to the challenge, see Quantum Sovereignty: Inside the New Tech Arms Race · Index: Quantum Sovereignty Topic

Introduction

Governments are increasingly treating quantum computers, communication networks, and sensors as critical assets – much like oil in the 20th century or semiconductor chips today. Quantum sovereignty has become a strategic imperative. The term refers to a nation’s ability to develop and control quantum technologies within its own borders, without undue reliance on foreign powers.

The motivation is clear: whoever leads in quantum tech could gain tremendous economic and security advantages, and no country wants to be at another’s mercy when that time comes. As global alliances fray and trust in traditional partners (notably the U.S. these days) wanes, countries are scrambling to secure their “technological sovereignty” in quantum. Recent geopolitical developments – from tech trade wars to espionage scandals – have underscored that technological dependence can become a strategic vulnerability. In response, nations are pouring billions into quantum R&D and crafting policies to ensure they won’t be left behind. But achieving quantum sovereignty is far easier said than done, and it differs in important ways from other forms of digital or tech sovereignty.

In my earlier essay, I wrote that physics has become politics by other means – and that it shows up everywhere, from research funding to security policy. The point of “quantum sovereignty” is that it’s the moment this abstract geopolitical shift becomes concrete: the moment the “quantum cold war” stops being a metaphor and starts showing up in procurement rules, licensing decisions, vendor risk assessments, and national industrial policy. In other words: geopolitics becomes architecture.

What Is Quantum Sovereignty?

The term quantum sovereignty is used in two ways. Hard sovereignty means full-stack domestic control – design, manufacture, and operation without critical foreign dependency. Practical sovereignty means controlling outcomes and risk: keeping access, verification capability, and swap options even when alliances shift or exports tighten.

In practice, this implies a country could build a complete full-stack quantum ecosystem entirely within its national borders: from quantum chips and cryogenic hardware to software, algorithms, and encryption protocols. The allure of this vision is easy to grasp. Quantum computing and related tech are poised to be as transformational in the 21st century as semiconductors and the internet were in the last. A fully sovereign quantum capability would mean a nation can harness this power for its own economic growth and national security, without having to rely on others’ equipment or know-how. Especially for major powers, the idea of being dependent on a foreign supplier (or rival) for something as strategic as code-breaking quantum computers or unhackable communications is unacceptable. Thus, quantum sovereignty has become a buzzword in policy circles, often wrapped into broader calls for “strategic autonomy” or “technological sovereignty” in emerging technologies.

In the rest of this article, I focus on practical sovereignty: the operational response.

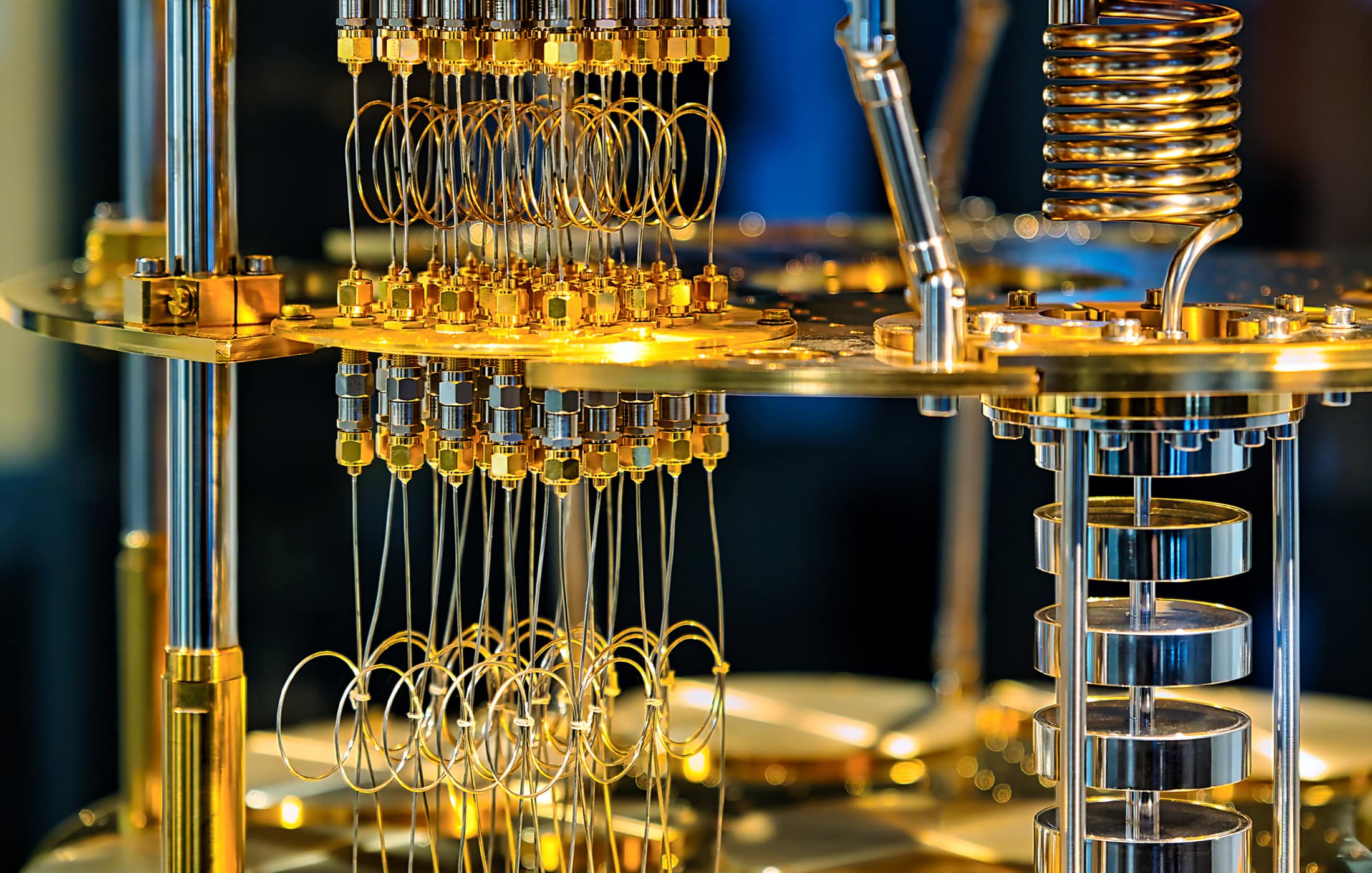

However, quantum sovereignty is an extremely ambitious goal – arguably far more challenging than sovereignty in classical digital tech. It’s not just about owning some data centers or using a domestic cloud service. Achieving true quantum independence means mastering a complex, cutting-edge R&D-intensive field from top to bottom. This includes: advanced physics research to create qubits, specialized manufacturing for quantum processors, ultra-sensitive instrumentation (e.g. lasers, cryostats operating near absolute zero), highly skilled talent, and robust software and cryptography. Each of these components is highly specialized and often concentrated in different parts of the world. No single country currently holds all the pieces of the quantum puzzle, which makes complete self-reliance a daunting prospect.

In fact, even the wealthiest and most technologically advanced players rely on international supply chains and collaboration in quantum science. The United States, for example, leads in superconducting qubits and software but has historically sourced many state-of-the-art cryogenic refrigerators from European firms. China made headlines with achievements like the Micius quantum satellite, yet it still needed to import certain high-end components (until recent export bans forced it to accelerate domestic substitutes). The EU boasts world-class research labs and companies in areas like quantum sensors and photonics, but it lacks other pieces such as large-scale chip fabrication for quantum processors (which exist mainly in the US and East Asia). Even Japan, perhaps the closest to true quantum sovereignty, achieved a 64-qubit homegrown quantum computer in 2025 with fully domestic hardware and software – an extraordinary feat – yet Japan could do so only by leveraging decades of industrial strength in electronics and still relies on certain foreign materials and know-how in the ecosystem. The Japanese example, while impressive, underscores how exceptional and difficult complete quantum self-reliance is in reality.

In summary, quantum sovereignty means total national self-sufficiency in quantum tech – a noble goal to strive toward for strategic reasons, but one that is almost prohibitively complex for all but maybe two or three global powers. This unique difficulty is a key reason why the concept of quantum sovereignty deserves its own discussion, separate from general tech sovereignty.

Why It’s Becoming More Important Now

Several converging geopolitical trends have propelled quantum sovereignty to the forefront in recent years. Foremost is a widespread erosion of trust in international technology supply chains, especially trust in U.S. tech leadership, which for decades was taken for granted. Allies and adversaries alike have grown wary of being too dependent on American technology for critical systems. Revelations of backdoors and surveillance didn’t spare even fundamental components – for instance, the 2013 leaks about a potential backdoor in a NIST-endorsed encryption algorithm sent shockwaves globally. Such incidents reinforced fears that reliance on foreign (particularly U.S.) technology could pose hidden risks. In the quantum context, that mistrust translates to concerns that if, say, U.S. companies or labs produce the only cutting-edge quantum computers or encryption systems, others could be left vulnerable or beholden to U.S. policies.

Here’s the tell that the era has changed: quantum isn’t just “research” anymore. It’s increasingly treated like controlled strategic infrastructure – where equipment gets denied, visas get harder, and scientists tread carefully. When that’s the environment, sovereignty isn’t a nationalist slogan; it becomes a practical response to friction, delays, and the risk of sudden cutoffs.

Geopolitical rivalries are amplifying these concerns. The U.S.-China tech competition has escalated to open restrictions: the U.S. government has imposed export controls to deny China access to advanced quantum technologies, adding Chinese quantum companies to trade blacklists and even weighing investment bans. This “weaponization” of tech supply chains cuts both ways. It spurs targeted nations to double down on indigenous innovation – for example, China’s response to Western semiconductor and telecom sanctions has been a rallying cry for self-reliance, and it is applying the same ethos to quantum by funding its own complete pipeline (from labs to fabs). Similarly, Russia, facing sanctions, has hinted at partnering with China on quantum research to avoid Western dependence. Even U.S. allies are hedging their bets. Europe, inspired by past lessons of being technologically outpaced, explicitly aims to build a “resilient, sovereign quantum ecosystem” so it is “not a mere consumer of others’ quantum tech”. European policymakers talk of a “sovereignty-first” approach: investing in European quantum chips, cryogenics, software, and securing supply chains to reduce reliance on U.S. or Chinese vendors. High-profile moves like the AUKUS pact (linking the US, UK, and Australia in defense tech sharing, including quantum) show that trust is now being “geo-fenced” among tight-knit allies, while others are left out. In AUKUS, the participants even agreed to loosen export controls among themselves for quantum technology – essentially creating an inner circle of quantum trust. From the outside, such developments only reinforce the impetus for other nations to develop their own quantum capabilities or form alternative alliances.

One reason quantum sovereignty feels sharper than, say, “cloud sovereignty” is that the chokepoints are stubbornly physical. In the earlier “physics cold war” lens, I described how even specialized lab infrastructure – cryogenic gear, photonics components, advanced electronics – can become a border-control issue. Once export controls start targeting quantum-enabling hardware (not just finished quantum computers), countries don’t merely want autonomy; they’re forced into building local capacity or negotiating access through trusted alliances.

Another factor is that quantum technology is dual-use and strategic. It has military and intelligence applications (breaking encryption, stealthier sensors, secure communications) alongside civilian uses. This makes governments view it through a national security lens. The European Union’s 2025 Quantum Strategy explicitly ties quantum tech to “strategic autonomy”, integrating it with defense and space initiatives to ensure Europe doesn’t become dependent in critical areas like secure communications or navigation. In short, quantum is now seen as part of the critical infrastructure of the future, on par with energy or conventional ICT. Thus, the timing: as prototype quantum devices inch closer to practical utility, nations are racing to position themselves. Over $40 billion in public funding has already been committed globally to quantum R&D, and more is coming – not just for scientific glory, but to secure those future capabilities on sovereign terms.

Finally, recent international initiatives and fractures have put quantum sovereignty in sharper relief. The breakdown of some traditional multilateral cooperation (partly due to great-power tensions) means countries can’t assume open access to each other’s tech. For example, the splintering of cryptography standards is a harbinger: the US led the first quantum-resistant cryptography standards, but China, Russia, and others are pursuing their own independent PQC algorithms, unwilling to trust the U.S. standards blindly. This “splinter-net” approach – multiple parallel standards and ecosystems – could very well happen in quantum computing hardware and networks if trust deficits persist. Each bloc might develop its own quantum cloud platforms, its own quantum communication satellites, etc., to avoid reliance.

In sum, the quantum sovereignty drive is a direct reaction to a world where globalization’s shine has dimmed: countries still collaborate in science, but they also want insurance policies. Quantum tech, being so strategic, is becoming one such policy – every major nation wants the option to go it alone if geopolitics require.

How Quantum Sovereignty Differs from Other Tech Sovereignty

It’s important to recognize that quantum sovereignty isn’t just “digital sovereignty 2.0.” Quantum technologies pose unique challenges that make achieving sovereignty fundamentally different from more mature tech domains.

In areas like cloud computing, telecommunications, or even classical computing, a nation can often substitute or develop good-enough local solutions covering perhaps 80-90% of the functionality of the global best. (For example, if access to top foreign cloud providers is cut off, a country could still deploy domestic data centers and open-source software to approximate the capability, albeit at some efficiency penalty.) Quantum, by contrast, is an all-or-nothing game – you either have the advanced quantum capability or you do not, and there are no easy “stopgap” substitutes for cutting-edge performance. If the world’s only 1,000-qubit quantum computers are made abroad and suddenly become unavailable, a country without them can’t simply spin up a local 900-qubit alternative; it might only have a 50-qubit machine, which is orders of magnitude less useful for the problems that matter. In other words, the performance gap in quantum can be overwhelming, and partial sovereignty may not suffice for strategic needs.

If the “physics cold war” story is the macro view – how competition reshapes science – then quantum sovereignty is the micro view: what the competition does to build-vs-buy decisions, resilience planning, and the question every government and board eventually asks: “What happens to us if the supply shuts off?”

A related difference is the nascent, experimental nature of quantum tech. Unlike classical digital tech – which benefited from decades of standardization, commoditization, and wide talent pools – quantum tech is still largely confined to labs and specialized companies. The supply chain is bespoke and fragmented, with critical expertise scattered globally. In classical computing, one can source standard components (CPUs, memory, disks) from multiple suppliers and build a near-state-of-art system locally. In quantum, many components are not interchangeable or mass-produced; they often originate from the few places that have spent years developing that niche. For example, ultra-low-temperature dilution refrigerators (essential for superconducting qubits) are made by only a handful of companies worldwide, mostly in Finland and the US. If those sources are cut off, it’s not trivial for another country to start making its own dilution fridge – it requires deep cryogenics expertise and manufacturing capability that can’t be conjured overnight. This contrasts with, say, conventional software, where losing access to a foreign vendor might be mitigated by using open-source alternatives or local developers. In quantum hardware, there are no open-source qubits, and the barriers to entry are enormous.

Furthermore, quantum talent and knowledge are limited resources concentrated in a few top universities and firms. Digital sovereignty often leverages the ubiquity of skills (many nations have plenty of software engineers to deploy on local projects). But quantum demands PhD-level specialists in physics, engineering, and math – and there’s a global shortage of such experts. Smaller countries especially struggle to train and retain quantum scientists, meaning they must collaborate or import talent to advance. This makes pure sovereignty even less realistic: you might build a quantum lab, but if all the leading experts in a certain subfield reside abroad, you’ll need cooperation to stay at the forefront.

Another difference is the pace of innovation and uncertainty. With cloud or telecom, the technology trajectory is fairly well known (incremental improvements, well-understood architectures). In quantum, we’re still figuring out the fundamentals – different modalities (superconducting, trapped ions, photonics, etc.), new algorithms, error-correction breakthroughs are emerging. No one country (or company) can explore all paths efficiently. So whereas digital sovereignty might be achieved by investing in a known stack (e.g. building domestic data centers, using a domestic operating system), quantum sovereignty would require betting on the right horse among many bleeding-edge approaches. The risk of betting wrong is high if done in isolation. This is why even powers like the EU acknowledge they cannot cover all bases alone and explicitly call for “diversify[ing] partnerships and reduc[ing] dependencies” in quantum development. In classical tech sovereignty debates, one often hears “we’ll just make our own cloud” or “use our own open-source alternative.” In quantum, such statements are rarer, because making your own full quantum stack is a multi-billion-dollar, decade-long endeavor with uncertain outcome.

In short, quantum sovereignty is a far tougher nut to crack than typical digital sovereignty. It’s less about having the will to unplug from foreign tech, and more about the capability to do so. With enough political will, a nation can force itself off foreign software or networks (as Russia has attempted with its “RuNet” or China with its walled garden apps) – painful but feasible. With quantum, no amount of will can overcome scientific and engineering gaps in the short term. There is no 90% solution in quantum; falling short of the cutting edge often means falling completely short of usefulness. This reality is forcing nations to think creatively about how to attain “sovereignty” in a field where going it alone may be impractical. That leads us to emerging strategies that blend independence with cooperation.

Strategies for Achieving Quantum Sovereignty

If outright quantum autarky is out of reach for most, what can nations do to ensure they aren’t left vulnerable? The answer lies in adopting a mix of strategies that balance self-sufficiency with collaboration – aiming for what I call “sovereign optionality” (See part 5 of the series), i.e. maintaining the option to rely on oneself if needed, while tapping a network of allies and global innovation to stay at the forefront. Below are several key approaches policymakers and enterprise leaders are pursuing to bolster their quantum sovereignty:

Invest in Domestic Capabilities (Selective Self-Reliance)

Every nation serious about quantum sovereignty is heavily investing in homegrown quantum research, talent development, and startups. The goal isn’t necessarily to cover the entire supply chain, but to ensure core strategic pieces can be produced at home. For example, the EU and UK are funding indigenous projects for quantum chips, cryogenic equipment, and encryption techniques, so that they have domestic sources for these critical components. Japan’s achievement of a fully homebuilt quantum computer shows the payoff of long-term investment in local expertise. By nurturing domestic quantum companies and labs (through national quantum programs, grants, and procurement), countries aim to have at least the minimum viable quantum toolkit under their sovereign control.

Standardize Interfaces & Embrace Open Architectures

A powerful way to reduce dependency is to design quantum systems that are interoperable and modular. If hardware and software components adhere to common standards, one supplier can be swapped for another with minimal disruption. This prevents vendor lock-in and gives nations flexibility.

Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) is an emerging approach exactly along these lines – it envisions quantum computers built from mix-and-match parts (much like a classical PC built from different vendors’ CPU, GPU, etc.) rather than a closed proprietary stack. By pushing for open standards (e.g. common qubit control protocols, network interfaces, error-correction formats) and supporting modular designs, governments “ensure they aren’t locked into a single vendor or supply chain”. The benefit is agility: if a foreign Partner A becomes untrustworthy or unavailable, you can plug in Partner B’s component.

Seen through the “physics cold war” lens, QOA is also a kind of geopolitical design pattern: it reduces the chance that a single export-controlled component – or a single untrusted vendor – can freeze an entire national program. You’re not making quantum “apolitical.” You’re engineering fallback options into the stack. We’re already seeing movement here – industry consortia and IEEE/ISO groups are working on global quantum standards, and many researchers share open-source software. QOA in action can be seen in projects like the University of Naples’ recent 64-qubit quantum computer: it combined a Dutch-made quantum processor with locally integrated control electronics and a Finnish cryostat. This “product of the Quantum Open Architecture model” significantly lowered the time and cost to build a world-class system, compared to the old route of either buying a full foreign system or building one from scratch. As QuantWare (the Dutch QPU supplier for Naples) noted, QOA is putting world-class quantum computers in the hands of a much wider ecosystem than just the big tech giants. By embracing open, modular architectures, countries and even corporations can assemble cutting-edge quantum machines using whichever components are available from allies or domestic sources, sidestepping single-supplier chokepoints.

Cultivate Multiple Partnerships (Diverse Alliances)

Rather than the old approach of picking one “national champion” or sole foreign partner, quantum sovereignty through partnership means engaging with many players so no single relationship is critical. The UK’s 2023 quantum strategy explicitly maps out partnering with different countries for different strengths – e.g. working with Germany on photonics, with the Netherlands on semiconductors, Japan on materials, Canada on quantum software. This “don’t put all eggs in one basket” philosophy ensures that if any one ally withdraws or any one import is blocked, alternatives exist. The European Commission similarly seeks to “diversify partnerships and reduce dependencies” by collaborating with the US, Canada, Japan, and others on joint research, shared testbeds, and aligned standards. In practice, a nation might concurrently participate in a U.S.-led project on quantum networking, an EU consortium on quantum materials, and a regional alliance on training quantum talent. By maintaining a web of collaborations, countries keep access to global innovations and know-how, while also building goodwill that can translate into mutual support. Crucially, this includes alliances for security: sharing quantum encryption networks among trusted partners (like EuroQCI in the EU, or AUKUS sharing quantum tech among allies) to collectively reduce reliance on outsiders. In essence, sovereignty is pursued as a team sport among friends – strengthening each member’s position without isolation.

Focus on Niche Strengths

A smart sovereign strategy is recognizing you can’t do it all, and instead doubling down on areas of comparative advantage. Many mid-sized countries are choosing specific quantum niches to excel in, then trading expertise with others. A recent analysis of Global South quantum programs noted that trying to cover the full quantum stack spreads resources too thin; it’s wiser to become world-class in one segment and collaborate for the rest. For instance, Australia has focused heavily on quantum sensing and photonic qubits (leveraging its physics research base), while Switzerland (via ID Quantique) is a leader in quantum encryption devices. By being indispensable in one subfield, a country gains bargaining power and joins global value chains instead of being a mere consumer. This approach is akin to how different European nations specialize in aerospace vs. automotive vs. pharmaceuticals, yet collectively the EU has a broad tech portfolio.

In quantum, such specialization could mean one country provides the best quantum error-correction software, another mass-produces a type of qubit, another pioneers quantum algorithms for finance, etc. Together they achieve a level of sovereignty through interdependence – each controls a key piece, and by pooling those pieces via alliances, they are collectively sovereign (without each one redundantly reinventing everything). This not only conserves resources but also accelerates progress by avoiding duplication.

Secure the Supply Chain and Knowledge Base

Beyond developing front-end technology, nations are also securing upstream inputs and knowledge to guard against external shocks. This includes stockpiling or domesticating sources of critical materials (for example, isotopes or rare-earth materials needed for quantum devices) and maintaining domestic capability in foundational technologies (like precision timing, high-performance computing, classical chips to control qubits, etc.)

It also means training a quantum-ready workforce at home – funding scholarships, dedicated quantum engineering programs, and attracting talent back from abroad. A country might tolerate using a foreign quantum cloud service in the interim, but it will insist on training its own scientists on how that system works, so it can build or effectively use a similar one later.

We see this in arrangements like the IBM-Fraunhofer partnership in Germany: Germany hosted IBM’s quantum system on its soil, giving local researchers full access and hands-on experience, essentially “importing” capability in a sovereign-friendly way. That early experience helped Germany then develop its own prototypes. Such measures ensure that even when foreign tech is used, the critical know-how and human capital stay local.

Additionally, many governments are implementing policies (like export controls and foreign investment screening) to prevent losing key quantum intellectual property or companies to outside takeover. For instance, the EU and UK have added certain quantum technologies to their controlled export lists, and the U.S. has restricted China’s access as mentioned. While this can complicate global cooperation, from a sovereignty standpoint it’s about guarding the crown jewels and avoiding single points of failure in the supply chain.

People

There’s another supply chain that’s easy to miss because it doesn’t ship in containers: people. In the earlier cold-war framing, I explored how scientists themselves become strategic terrain – recruitment pressure, security vetting, and even speculative “defector” scenarios that shatter research trust overnight. Whether or not those extremes occur, the policy implication is immediate: a sovereignty strategy that ignores talent mobility, research security, and ethical guardrails is incomplete.

Quantum sovereignty isn’t only about owning hardware; it’s also about keeping a credible, safe environment where the best researchers can work without turning every collaboration into a counterintelligence drama.

By combining these strategies – investing at home, collaborating abroad, standardizing for flexibility, and protecting key inputs – nations aim to achieve a balanced form of quantum sovereignty. It’s not the old model of isolation and autarky, but rather what we earlier noted as “sovereign optionality.” This approach acknowledges reality: you stay plugged into global innovation (so you don’t fall behind), but you simultaneously build insurance in the form of local capacity and diverse ties (so you’re not cornered if geopolitics turn sour).

The Quantum Open Architecture ethos bolsters this by making the technology itself more plug-and-play, reducing the power of any single supplier to hold others hostage. In effect, the pursuit of quantum sovereignty is evolving from a purist “do everything yourself” mindset to a more nuanced strategy of resilience and choice.

Conclusion

Quantum sovereignty has swiftly moved from a fringe idea to a central objective for policymakers and tech leaders in this new era of geopolitical tech competition. It represents both the hope of reaping quantum technology’s benefits for one’s own nation, and the fear of being left dependent or vulnerable in a future where quantum capabilities determine economic and security clout. Achieving full sovereignty – the ability to build every piece of a quantum computer or network domestically – will remain an immense challenge, one that only a superpower or two might attempt in full. For most countries and organizations, the more practical goal is to ensure access to quantum technology on favorable terms, through a mix of local development and allied cooperation. As we’ve discussed, this means rethinking “sovereignty” not as isolation, but as leverage: the leverage to choose among options, to plug into a global ecosystem or detach from it as needed.

The current geopolitical climate, with its eroding trust and techno-nationalism, makes the quest for quantum sovereignty understandable – no one wants to wake up to a “quantum surprise” where a rival holds all the keys. But it also teaches that closing off is not the answer; quantum progress has always thrived on international collaboration and shared knowledge. Going forward, the most successful nations will likely be those that skillfully blend self-reliance with openness – building robust domestic quantum industries and talent, while also forging links (and common standards) that let them tap into breakthroughs anywhere in the world. Quantum Open Architecture and similar initiatives will further level the playing field, allowing smaller players to assemble top-tier systems without reinventing every wheel.

A final, deliberately optimistic – but strategically useful – thought experiment: imagine a world where one bloc reaches a decisive quantum breakthrough earlier than expected. In the “cold war” story, that’s the nightmare scenario that makes everyone panic. In the sovereignty story, the lesson is more procedural than dramatic: the time to build options is before the shock, not after it. Sovereignty isn’t a victory lap; it’s a hedge – one that must be assembled while you still have access to global supply chains, global talent, and global standards forums.

In the end, quantum sovereignty is about freedom of action: the freedom to pursue your national interests in the quantum era without being coerced or left behind. By investing wisely, partnering widely, and insisting on interoperability and trust, countries and enterprises can approach this ideal. They may not all achieve 100% sovereignty (nor need to), but they can achieve quantum security and autonomy – a position where no single supplier or foreign power can dictate their quantum future. In a world where quantum technology is power, preparing for sovereign control of that power is indeed a prudent strategy. The winning approach is to stay agile, stay connected, and ensure you always have options. Quantum sovereignty, pursued with this agility and foresight, will be a cornerstone of national innovation strategies in the years ahead.

For the broader context – why deep physics fields like quantum, advanced materials, and energy are now entangled with geopolitics – see “Physics at the Heart of the New Cold War.”

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the cquantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.