Quantum Sovereign Optionality: Agility Over Autarky

Table of Contents

Introduction

In the black depths of the ocean, a diminutive deep-sea octopus thrives not by brute force but by agility and adaptability. It contorts through narrow crevices, changes color to elude predators, and ekes out a living under crushing pressures. In the race for cutting-edge quantum technology, many nations find themselves in a similarly harsh environment – facing giant competitors and high stakes. Like the octopus, their best hope isn’t to out-muscle the superpowers, but to out-maneuver them.

If you want the full framing of why sovereignty pressure is rising – and how it turns into architecture, procurement, and standards – start with my companion essay on Quantum Sovereignty; this piece zooms in on the practical strategy for countries that need leverage without pretending they can rebuild the full stack alone.

Here I’ll try to explore a paradigm I call “sovereign optionality” or maybe “sovereignty agility” – still trying to decide – a strategy for nations to secure quantum tech independence through flexibility, resilience, and clever collaboration, rather than an all-or-nothing quest for total technological sovereignty.

This idea and the article are informed by countless discussions I had over recent years with governments trying to figure out how to achieve complete quantum tech sovereignty. Something which, in my opinion, is now achievable neither it’s wise to try it.

The Allure of Quantum Sovereignty (and Why It’s So Challenging)

I treat “quantum sovereignty” here mainly as the problem statement; for a deeper breakdown of the sovereignty stack (and why it behaves differently from cloud or classical tech sovereignty), see Quantum Sovereignty.

Technical sovereignty has become a buzzword in geopolitical and tech circles. As global alliances fray and trust in traditional partners wanes, countries are scrambling to assert control over critical technologies.

In the quantum arena, this instinct translates into an ambitious goal: build a complete, full-stack quantum ecosystem entirely within national borders. The allure is understandable – quantum computers, sensors, and communications could be as transformational in the 21st century as semiconductors were in the 20th. No nation wants to be dependent on others for such strategic capabilities, especially when future economic and national security might hinge on them.

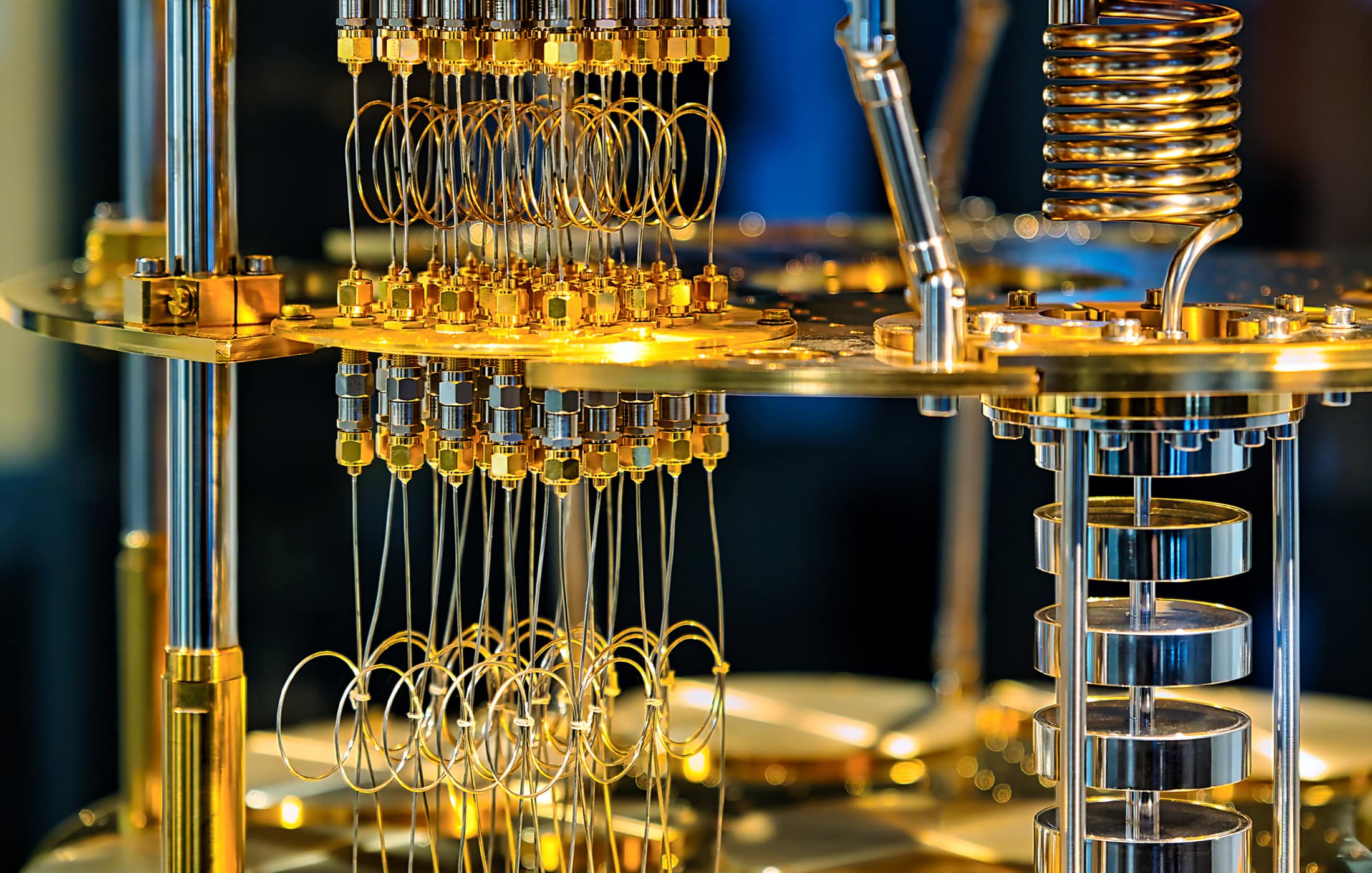

However, pursuing quantum sovereignty – the ability to design and manufacture every layer of quantum tech domestically – is an immense challenge, bordering on the impossible for most countries. Quantum technologies comprise a complex stack of interdependent components: advanced materials and isotopes, ultra-sensitive sensors, cryogenic or laser-based hardware, control electronics, specialized software, and a rare breed of scientific talent. These critical pieces are scattered across the globe, residing in pockets of expertise in different nations. Unlike classical computing (where decades of standardization have made components like chips, memory, and software relatively modular), quantum’s nascent supply chain is bespoke and fragmented. As one World Economic Forum report noted, developing commercial quantum systems is “necessarily a global undertaking, with state-of-the-art knowledge and necessary components scattered across the world”. In other words, no single country holds all the keys.

Even the wealthiest and most technologically advanced nations struggle with this reality. The United States, China and the European Union, for example, have each invested many billions to lead in quantum – yet each still relies on international collaboration for certain parts. China’s well-known quantum achievements (like the Micius satellite enabling global quantum-encrypted communications) showcase its prowess, but China has also faced restrictions on importing crucial tools (e.g. high-end cryostats and control electronics) due to export controls. Paradoxically, those very restrictions have spurred China to accelerate domestic alternatives – from microwave interconnects to dilution refrigerators – in a bid for self-reliance. The U.S., for its part, benefits from a vibrant private sector (IBM, Google, countless startups) and strong alliances (even the AUKUS security pact includes quantum cooperation ), but even America doesn’t produce everything in-house – for instance, many state-of-the-art cryogenic refrigeration systems historically come from European firms.

Japan is perhaps the closest example of achieving quantum sovereignty. In 2025, Japanese researchers unveiled a fully homegrown superconducting quantum computer built at Osaka University – complete with domestically manufactured qubits, control electronics, and cryogenic refrigeration – all running on a locally developed open-source software stack. This achievement, powered entirely by Japanese components and code (the software stack is tellingly nicknamed “OQTOPUS”), marked “full national self-reliance in quantum hardware and software” for Japan.

Yet, as impressive as Japan’s feat is, it underscores how exceptional such capabilities are. Japan managed it only by leveraging a broad industrial base (precision electronics, semiconductor tooling, materials science) built over decades. Few countries have such an ecosystem to draw on. And even Japan still depends on foreign partners for certain upstream inputs – for example, sourcing some specialized materials and benefiting from scientific exchanges – not to mention that Japanese companies remain active players in international projects.

Europe likewise views quantum tech as vital to technological sovereignty, but Europe’s situation illustrates the difficulty of covering all bases. The EU has world-class quantum researchers and some leading companies (for instance, French and German startups building quantum processors, a Finnish firm dominating quantum cryostats, etc.), yet it lacks other pieces – like large-scale classical chip fabrication for quantum control, which currently exists mainly in the US and East Asia. The EU’s own strategy candidly admits that Europe must secure supply chains and build up an “autonomous, sovereign, and competitive” quantum industry – a tall order given today’s gaps. In practice, Europe is not isolating itself: the European Commission explicitly calls for “diversify[ing] partnerships and reduc[ing] dependencies” via bilateral and multilateral cooperation with like-minded countries. In fact, the EU is partnering with the US, Japan, Canada, and others on joint research programs, aligned standards, reciprocal access to infrastructure, and even shared quantum testbeds. This is a recognition that going it alone isn’t feasible – even for a 27-nation bloc with a combined $16 trillion GDP. Europe wants more quantum autonomy, yes, but it’s hedging that bet through alliances and common standards.

The bottom line is that a full-stack quantum buildout is prohibitively expensive and complex for all but perhaps two or three global powers – and even they face significant hurdles. For most others (and arguably even for the big players in the long run), insisting on 100% home-grown quantum tech could be a strategic misstep. It risks slower progress (by duplicating others’ work), higher costs, and isolation from the booming global innovation ecosystem. We’ve learned from fields like AI and semiconductors that innovation thrives in connected networks, not silos. Quantum is shaping up similarly: breakthroughs often come from international collaboration, and supply chains are intertwined. Does this mean smaller countries should simply give up and accept permanent dependence? Not at all. But it means we need a different framing – beyond the all-or-nothing notion of sovereignty.

From Sovereignty to Sovereign Optionality

Instead of pursuing absolute quantum sovereignty, nations should pursue “sovereign optionality.” This concept shifts the focus from total self-sufficiency to an approach centered on resilience, flexibility, and strategic choice in quantum technology. Sovereign optionality or sovereignty agility is about ensuring you have options and can pivot quickly – rather than trying (and likely failing) to do everything domestically.

In practice, what would sovereign optionality entail? Here are five key pillars of this approach:

Standardize Interfaces and Embrace Open Platforms

Think of sovereign optionality as the implementation strategy that makes quantum sovereignty realistic: not by eliminating dependencies, but by designing systems – and policies – for fast pivots when dependencies become liabilities.

The single biggest enabler of agility is interoperability. If your quantum systems adhere to common standards and modular interfaces, you can mix-and-match components or swap out a foreign supplier for a domestic one (or vice versa) with far less friction.

A great analogy comes from the digital world: Portugal’s government famously adopted a “sovereignty through standards” strategy for its digital services. Rather than building every component in-house, they defined rigorous open interface specifications (APIs, data formats, etc.) and let a competitive marketplace provide the implementations. The result? Portugal modernized its digital infrastructure rapidly while retaining full control over how systems work – if not over who exactly provides them. When one major vendor attempted to impose unfavorable terms, Portugal simply swapped them out – an easy move because interoperability was baked in from the start.

In quantum tech, the same lesson applies. By pushing for standardized protocols (common qubit control languages, network interfaces, error-correction formats, etc.), countries can ensure they aren’t locked into a single vendor or supply chain. If Partner A falters or becomes untrustworthy, you can plug in Partner B’s component with minimal redesign. Thankfully, there is movement in this direction: international bodies (IEEE, ISO and others) and industry consortia are already working on global quantum standards for computing, communication, and sensing. Governments should throw their weight behind these efforts. Standards will make quantum systems more reliable, interoperable and cheaper at scale, which benefits everyone – and they particularly empower those worried about sovereignty, since open standards prevent proprietary lock-in. (Likewise, embracing open-source software in quantum research – as much of the community does – contributes to interoperability and agility by ensuring transparency and compatibility.)

Cultivate Multiple Partnerships (Don’t Put All Eggs in One Basket)

Traditional sovereignty thinking often led countries to pick one champion vendor (ideally domestic) and go all-in. Sovereign optionality, in contrast, means maintaining a diverse ecosystem of partners – both domestic and foreign – so that you always have alternatives.

It’s essentially a multi-vendor, multi-ally strategy. For example, the United Kingdom’s recent quantum strategy explicitly recommends ensuring access to critical quantum capabilities by “combining domestic investment with strategic international partnerships.” It even maps out specific pairings: the UK should partner with Germany for photonics and lasers, the Netherlands for semiconductors, Japan for materials and electronics, Canada for quantum cryptography and software. The logic is clear: each partner brings something unique, and by engaging with many, Britain can fill gaps without having to master everything alone. Crucially, if any one relationship sours (for political or commercial reasons), there are other options in the network.

We see this principle in the EU’s approach as well – the European Commission is expanding cooperation with a host of countries to “diversify partnerships and reduce dependencies,” based on complementary strengths and mutual trust. In quantum terms, a country might simultaneously collaborate with one ally on building a quantum communication network, with another on developing quantum processor chips, and with a third on software algorithms. By running these partnerships in parallel, you reduce the risk that a single point of failure will derail your whole program. This is essentially the supply-chain resilience concept applied to R&D and innovation: always have multiple sources or collaborators for each crucial input.

Focus on Niche Strengths – Don’t Spread Yourself Too Thin

Sovereign optionality also means knowing your strengths (and weaknesses) and leveraging them. Instead of trying to cover the entire quantum waterfront, countries – especially those with limited resources – should specialize in areas where they have a comparative advantage, and team up for the rest.

A recent analysis of quantum strategies in the Global South put it bluntly: rather than spreading scarce resources across the full quantum stack, countries can focus on segments where they hold comparative advantages , whether that’s software, communications, materials science, or certain applications tied to national needs. For instance, a nation with a strong telecom industry might concentrate on quantum encryption and networking, while another with semiconductor expertise goes for hardware fabrication. Indeed, India, Brazil, South Africa and others are already taking this to heart – they aren’t trying to clone Google’s or IBM’s entire quantum computer, but are zeroing in on software and on specific use-cases where they can excel.

By becoming world-class in one link of the value chain, a country gains leverage: its partners will rely on it for that piece, just as it relies on them for others. This kind of “niche specialization” ensures you remain a contributor, not just a consumer, in the global quantum ecosystem. It’s a smarter form of sovereignty – one built on interdependence, where each party is indispensable in some way. Over time, a network of such specializations can collectively provide a fuller stack, without each member duplicating efforts. (It’s akin to how the European Union functions internally: one nation builds the airplanes, another builds the rockets, another the high-speed trains, and through trade and cooperation, everyone benefits.)

Build Agile Domestic Capabilities for Verification and Integration

Embracing foreign partnerships and components doesn’t mean blindly trusting everything you import. To maintain true sovereignty, countries should invest in local expertise to verify, validate, and securely integrate quantum technologies developed elsewhere. This means establishing independent testing labs, certification bodies, and “red team” groups that rigorously evaluate any externally sourced quantum hardware or algorithms.

For example, if you buy a quantum random number generator or a QKD encryption box from abroad, having domestic cryptography experts who can test its security (or even open up the device to inspect for backdoors) is vital.

Likewise, training a cadre of quantum engineers who can integrate multiple vendors’ components into a seamless system gives you the freedom to mix-and-match without reliance on any single supplier’s consultants. Think of it as developing an in-house “systems integrator” capability. The more your people understand the technology, the less you’re at another’s mercy.

This also feeds back into the standards point: knowledgeable local teams can help set the interface standards and protocols mentioned above, ensuring they meet your national requirements. Policymakers can support this pillar by funding quantum science education, specialized technical training, and exchange programs to cultivate homegrown talent. They can also require technology transfer as part of contracts with foreign providers – e.g. mandate that your local scientists get access to the design IP or get hands-on training during the deployment of a foreign-sourced quantum system.

The goal is that even if the hardware is made abroad, the brains overseeing it are domestic, preserving sovereign control over how it’s used and ensuring confidence that it’s not a black box. (Many countries already do this in other fields – for instance, nations that import defense equipment often have local military engineers inspect and integrate those systems into their forces. We should take a similar approach for quantum tech procurement.)

Streamline Policy for Quick Swaps and Adaptation

Governments should align their policies, procurement rules, and diplomacy with the agility philosophy. That means, for example, avoiding overly rigid long-term contracts that lock you into one vendor without exit ramps. Instead, include clauses that require knowledge transfer or escrow of critical design information, so that if you need to switch suppliers, you can do so without starting from scratch.

Set up contingency plans for supply disruptions: if Country X can no longer export a component you rely on, have a Plan B ready with Country Y or a modest local substitute. This might entail maintaining some domestic production capability as backup, even if it’s not cutting-edge – similar to how some nations keep older semiconductor fabs running for security reasons, in case chip imports are cut off.

On the diplomatic front, sovereign optionality entails actively participating in international forums (so you’re aware of the latest developments and can influence global norms) and engaging in “technology diplomacy.” By staying friendly or at least cordial with multiple tech powers, a country increases its options.

We’ve seen encouraging moves like India partnering with Finland on quantum computing research and simultaneously launching a joint quantum coordination mechanism with the US – India is wisely ensuring it’s plugged into quantum innovation from different sources. Ultimately, agility-friendly policy is about being prepared: assume that some partnerships may collapse or some tech pathways will fail, and create an environment where Plan B or C can kick in with minimal disruption.

Flexibility should be built into everything from procurement tenders (e.g. requiring interoperable designs) to export control regimes (so you can import from various sources) to visa policies (to attract foreign quantum talent if needed). In short, remove the bureaucratic friction that would slow down a fast pivot if circumstances change.

This is what I mean when I say geopolitics becomes architecture: procurement rules and interface choices determine whether you can actually pivot when trust breaks or exports tighten.

Why the EU Could Lead on Sovereign Optionality

While any nation can adopt the agility mindset, the European Union is uniquely positioned to champion this approach – perhaps even more so than trying to be completely sovereign in quantum technology. The EU’s circumstances make this kind of agility both necessary and advantageous:

First, Europe has learned the hard way in recent years that over-reliance on a single supplier or nation can be dangerous. From energy supply shocks to semiconductor shortages, Europe understands the perils of dependency. This has driven the EU’s broader push for “strategic autonomy.” In quantum, as discussed, Europe doesn’t have it all – but it does have a bit of everything, spread across different member states and allied nations. By knitting these pieces together through standards and smart policy, the EU can effectively create a sovereign-like outcome (access to full-stack capabilities) without every piece being on EU soil. Brussels already encourages this. The EU’s Quantum Europe 2030 Strategy explicitly calls for partnering with like-minded countries and expanding international cooperation to secure supply chains. Notably, Europe is working with allies like Japan, South Korea, and Canada on quantum R&D projects, and has even signaled openness to emerging quantum players around the world. This openness is a strategic asset – the EU can be the hub of a global quantum network, trusted by many because of its stable regulatory environment and emphasis on ethics. In a sense, the EU can turn “being everyone’s friend” into a strength: it can acquire tech from anywhere, set rules that promote interoperability, and not be seen as threatening in the way the US or China might be.

Second, the EU’s massive single market gives it leverage to push standards that foster agility. We’ve seen this before: when Europe mandated a common charging port for mobile phones, global manufacturers complied because they couldn’t ignore the EU market. Similarly, if the EU insists that quantum vendors adhere to certain interface standards or security certifications to sell in Europe, those standards could become de facto global norms. This would reduce vendor lock-in not just in Europe but worldwide. The EU could, for example, promote a standard quantum computing API or require a certification for QKD devices such that multiple products become interchangeable. This standard-setting power is a form of “soft sovereignty” that doesn’t require owning the tech, but rather guiding its development. By leading on norms and protocols, Europe can ensure it can always swap out any component that fails to meet its criteria (because a compliant alternative will plug in seamlessly). The World Economic Forum has pointed out that standards make quantum tech simpler for users and facilitate adoption across governments and companies – a win-win that Europe can rally others around. Given that European values favor openness, competition, and privacy, the EU’s push for open standards would likely be welcomed by many smaller countries too. It’s an approach that wields Europe’s regulatory clout to benefit both itself and the broader global ecosystem.

Third, within the EU, a “sovereign optionality” model aligns with the Union’s collaborative nature. No single European country – not even Germany or France – can dominate all aspects of quantum. But each has its specialties: Finland excels in cryogenics, France in neutral-atom qubit systems, Germany in superconducting processors, the Netherlands in quantum networking, Austria in quantum cryptography, and so on. If the EU encourages each member to focus on areas of strength and then share the fruits through an integrated market, Europe collectively reduces its need to rely on external sources at all. The EU’s Horizon Europe and Digital Europe programs are already funding cross-border quantum projects in this spirit. By doubling down on this approach (e.g. creating EU-wide “quantum innovation hubs” that combine multiple nations’ expertise), Europe can achieve something close to full-stack capability as a bloc, without each country needing full-stack as an individual. Importantly, Europe isn’t closing off external sources either; it’s pursuing both internal capacity and external partnerships. That balanced agility approach is evident in moves like the EU–US Trade and Technology Council, which has a quantum cooperation component, and EU–Japan joint research calls. The likely result is that by 2030, Europe will have a robust homegrown quantum sector and deep links to every other major quantum power. That is far more resilient than trying to erect a hard tech border. It ensures Europe won’t be left behind if, say, a breakthrough happens elsewhere – because Europe will either be part of it or can quickly adopt it.

Finally, the EU’s emphasis on values and trust could make it a leader in establishing trusted supply chains. For instance, the EU could certify certain suppliers (domestic or foreign) as meeting European security standards, and then require that critical quantum infrastructure use only these trusted, certified components. This wouldn’t mean everything has to be made in Europe, but it would mean everything is vetted to Europe’s satisfaction. By doing the hard work of evaluation and standardization, the EU would gain the agility to replace any component that doesn’t pass muster with one that does. In contrast, a country that insists on doing everything in-house might ironically become more brittle – if a flaw or vulnerability is discovered in its sole domestic technology, it has nowhere else to turn. Europe, with multiple partners and certified options, could simply switch to another supplier. In this way, sovereign optionality is actually safer than pure sovereignty because it avoids single points of failure. The EU, which is institutionally geared toward redundancy, consensus-building and risk mitigation, is well-suited to think this way. This is why the EU can and should pioneer the sovereignty agility model in quantum. If Europe embraces this approach and succeeds, it will not only secure its own interests but provide a template that other regions can follow.

A Playbook for Emerging Quantum Players: Agility Over Autarky

What about countries outside the top-tier quantum powers? Regions like the Gulf, Southeast Asia, or smaller economies often feel they are starting far behind and risk being left out of the quantum revolution. For them, the temptation might be to try to “catch up” by pouring money into their own quantum labs and companies – essentially attempting to buy sovereignty. I would caution that a strategy of pure autarky is likely to lead to frustration and wasted resources if they aim to replicate what the US, China or EU have done. Instead, sovereign optionality is even more pertinent for these players.

Take Saudi Arabia as an example. The Kingdom has signaled grand ambitions to be a “global hub for the quantum economy,” aligned with its Vision 2030 plan to diversify beyond oil. But Saudi Arabia is realistic about its current capabilities – which is why its early moves have been partnership-centric. In May 2024, Saudi Aramco partnered with France’s Pasqal to deploy the first quantum computer in Saudi Arabia (a 200-qubit neutral-atom machine). Rather than attempting to build a quantum computer from scratch domestically (which would have taken many years with uncertain success), Saudi effectively imported one – but crucially, did so in a collaborative way that transfers knowledge. At the same time, Saudi institutions are teaming up with established players on multiple fronts: Aramco with IBM on a local innovation hub, the new futuristic city NEOM with UK-based Arqit on quantum cybersecurity, and so on. These partnerships often include training local talent and jointly developing applications in energy, materials, and security. The approach accelerates Saudi’s learning curve dramatically. It is a textbook case of sovereign optionality: leveraging global tech while cultivating local expertise so that Saudis can eventually run and adapt the technology independently. Indeed, a recent World Economic Forum report on Saudi’s quantum landscape calls for establishing a “quantum foundry” – a domestic facility to prototype and manufacture quantum devices – but explicitly as part of bolstering collaboration and commercialization efforts, not isolation. In other words, even as Saudi builds some local infrastructure, it will remain connected to international networks of knowledge and supply.

For Saudi and others in similar positions (think the United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Brazil, South Africa, etc.), a few guiding points emerge:

- Invest in People and Pick a Focus. You can’t instantly buy a full quantum ecosystem, so start by developing a quantum-ready workforce through education, training abroad, and attracting global talent. At the same time, identify one or two niche domains to concentrate on – perhaps quantum encryption if cybersecurity is a national priority, or quantum sensors for oil exploration in the Gulf’s case. By being really good in a particular application, you gain a foothold in the global value chain. For example, Brazil has focused its efforts on quantum communications and software, aligning with its existing strengths in telecommunications and academia. It’s unrealistic to boil the ocean, but you can boil your cup of tea. Specialize in what matters most to your economy and where you have some comparative advantage; leverage others for the rest.

- Leverage Alliances – Both Big and Small. Form both “North–South” partnerships (with the big quantum countries) and “South–South” collaborations (with peers). The latter can amplify bargaining power and create shared platforms that none of you could build alone. We’re seeing early signs of this: India and Brazil, for instance, have discussed jointly setting up quantum research hubs, and a consortium of ASEAN countries is exploring pooling resources for a regional quantum network. Alliances can also give smaller countries a voice in standards-setting forums that they wouldn’t have alone. If a group of developing nations jointly proposes an interoperability standard, it’s harder for the big powers to ignore. Collective agility can complement national agility. As one think-tank report noted, forging alliances – whether through South–South coalitions or triangular cooperation with established powers – can unlock access to infrastructure and standards-setting bodies that would otherwise be out of reach. In other words, banding together can get you a seat at the table where the rules of the quantum future are being shaped.

- Use Procurement and Policy Creatively. Even if you aren’t a tech leader, as a government you are often a major customer. Use that clout to demand technology transfer and openness in any contracts. When buying a quantum solution, require that your local universities or companies are involved in the deployment, so they learn by doing. Set up regulatory sandboxes to pilot quantum tech from various vendors – this way your country becomes an attractive testbed for multiple providers, again diversifying your exposure. Some smaller nations have done well by being neutral grounds where international teams come to experiment (Singapore often plays this role in tech, for example). By being open and agile in your regulations, you can attract cutting-edge projects to your soil, which builds local know-how. Don’t underestimate the value of soft power: host international quantum conferences, sponsor training workshops, participate actively in global initiatives like the Quantum Computing User Forum or the Open Quantum Institute. These actions signal that your country is a welcoming node in the global quantum network. They increase the chances you’ll be included when big multinationals or research consortia roll out new technologies or pilot projects.

In short, emerging players should not aim to be self-sufficient; they should aim to be self-assertive. That means being proactive in shaping their quantum destiny through smart partnerships and strategic investments, rather than passive recipients of whatever technology trickles down to them.

The image we opened this article with – a deep-sea octopus surviving through stealth and adaptability rather than brute force – is apt here. Countries with fewer resources won’t win a quantum race by brute force; they’ll win by being agile, adaptable, and yes, a bit cunning in how they leverage bigger players’ strengths.

Conclusion

As quantum technology matures from lab curiosity to real-world infrastructure, every nation faces a crossroads in strategy. The instinct to chase absolute technical sovereignty – to build your own quantum computing stacks and encryption networks, independent of all others – is a natural response to geopolitical uncertainty. But as I’ve argued, for most countries this is a Sisyphean task and quite possibly a self-defeating one. Insisting on doing it all alone could leave you perpetually behind the curve, or isolated from the global innovation community which thrives on exchange. In a field evolving as rapidly as quantum (where today’s leader in one sub-field can become tomorrow’s follower in another), agility and resilience are more valuable than sheer ownership of technology.

Sovereign optionality is about maintaining sovereign control over your outcomes without necessarily controlling every input. It’s the idea that you don’t need to own the cow, as long as you have a reliable (and flexible) way to get the milk – and a backup plan if the milkman fails to show up. This approach enables nations to protect their core interests (security, economic growth, values) without retreating into silos. It’s a recognition that interdependence, if managed wisely, can be a strength. True sovereignty means choosing your dependencies wisely, not eliminating them entirely.

The vision I’m painting is not some naive kumbaya scenario of global harmony – rivalries and tech disputes will still exist. Rather, it’s a pragmatic roadmap for nations to ensure they aren’t left holding the short end of the qubit. By standardizing interfaces, partnering broadly, focusing on strengths, verifying imports, and staying nimble, a country can reap the benefits of worldwide quantum innovation and safeguard its national interests. Reliable allies may falter; cutting-edge suppliers may emerge or vanish – but with agile sovereign optionality, you can always adapt and pivot.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.