The Easiest Job in Quantum Computing – Being a Cynic

Table of Contents

As an advocate for quantum technologies, I’ve always enjoyed rigorous debates with skeptics. Recently, though, I’m seeing more drive‑by quantum cynicism – confident proclamations with no analysis behind them. Those exchanges yield no learning and drain time and energy. If you’re fully inside quantum research, you may not encounter much of this (and I envy you); but with only one foot in quantum tech and the other in business, cyber and geopolitics, these unproductive debates recently have become a daily occurrence.

Quantum computing is having a moment. Decades of deep theoretical work are rapidly translating into tangible hardware, sophisticated algorithms, and a burgeoning global ecosystem. It’s a field characterized by profound complexity, immense potential, and, inevitably, plenty of buzz.

Where there is potential, people flock. We have the dedicated scientists and engineers methodically tackling some of the hardest problems in physics and computation. But we also have the hangers-on. So let’s talk about the cast of adjacent characters in this quantum theater.

Grifters: Fearmongers and Snake Oil Peddlers

First, there are the outright grifters – the fearmongers. We know them well. These folks slither into the quantum space claiming insider scoops from shadowy agencies like the NSA. “Quantum computers are already here, breaking your encryption as we speak!” they cry, all while hawking overpriced “quantum-proof” solutions. It’s unethical snake oil, leveraging fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) to line their pockets. I’ve covered these charlatans before, so I won’t dwell on them. They’re a symptom of the field’s rapid growth: where there’s buzz, someone will try to monetize the panic.

Skeptics and Contrarians: The Valuable Critics

Then there are the thoughtful skeptics and honest contrarians. Contrarianism for its own sake isn’t productive. Yet the best of them operate in good faith as useful skeptics. They ask tough questions, challenge assumptions, and force us to re-examine our premises. They often bring a healthy dose of skepticism that can sharpen the discourse. Even when we disagree, the engagement can be valuable. It’s a dialectic process that ideally leads to a sharper, more robust understanding of the truth. We both tend to learn from the exchange.

In quantum computing, contrarians like Yann LeCun and Gil Kalai argue that scalability might be a pipe dream due to issues like decoherence (quantum states collapsing too quickly) and the enormous overhead of error correction (potentially needing thousands of physical qubits for one reliable logical qubit). They point out that current NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) devices are error-prone and limited in real-world applications. But here’s the key: these voices aren’t just nay-saying. They demand evidence, push for better benchmarks, and force the field to address weaknesses. This is valuable for tempering hype. At its best, contrarian skepticism is productive: contrarians engage, debate, and even pivot when new data emerges. When they provide well-thought-out arguments, that discourse is invaluable.

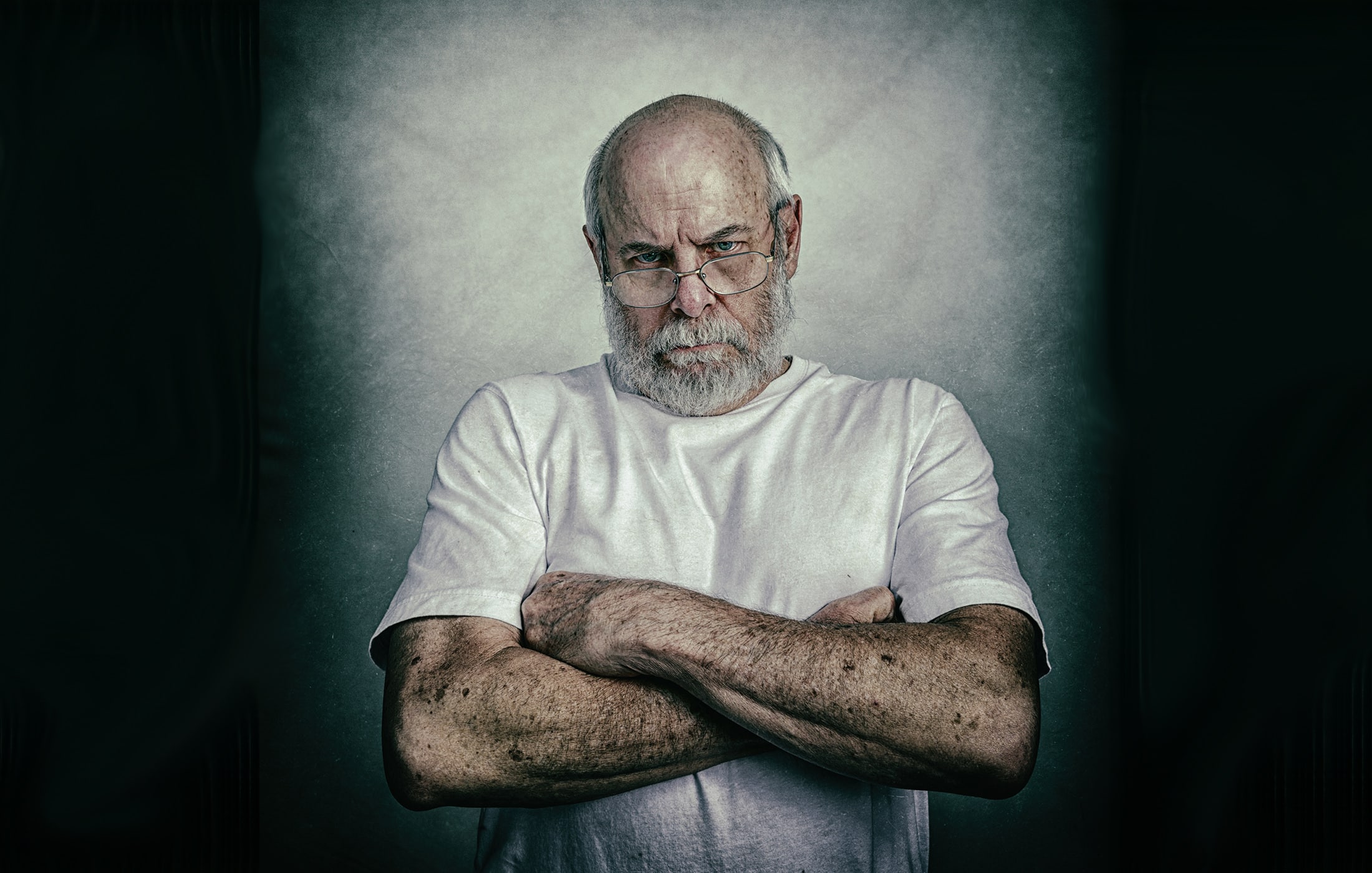

Cynics: Posturing Instead of Understanding

But there is a third group, perhaps the most corrosive to genuine discourse: the cynics. They perfectly illustrate a biting observation by Russell Lynes:

“Cynicism is the intellectual cripple’s substitute for intelligence.” – Russell Lynes (Lynes’s mid-century phrasing is pointed – he’s criticizing an attitude, not a physical condition.)

Lynes understood something profound: cynicism is often a defense mechanism for those who fear being wrong more than they desire to be right. It’s safer to dismiss everything than to engage with complexity and risk being caught believing in something that might fail. It shields the cynics from being wrong by never committing to a claim. But science is precisely the art of making claims strong enough to be broken – and then updating beliefs.

In the complex landscape of quantum technology, his quote highlights a fundamental truth: Understanding a difficult subject requires intellectual effort; dismissing it requires none. It takes years of specialized study to truly grasp the nuances of quantum mechanics, error correction, qubit modalities, and algorithm development. It takes seconds to type, “Quantum computers will never work.” Often because at some point someone of perceived authority made a similar claim (probably a more nuanced one, though), and not because the writer came to that conclusion after their own careful analysis.

Cynics haven’t done the hard work of grappling with quantum computing’s substance. Their engagement typically follows a predictable pattern, a kind of lazy playbook:

- The Unsubstantiated Pronouncement: “Quantum computers will never work.” Or its slightly more restrained cousin: “It’s always 20 years away. We won’t see anything useful for 50 years.” These are stated as gospel with zero evidence.

- The Deflection (Not Reflection): When pressed for reasoning, the cynic offers no data, no models, no analysis of qubit coherence times or error correction thresholds. Instead, they scoff and deflect. Their entire argument reduces to a rhetorical jab: “Oh, come on – you really think we’ll have a cryptographically-relevant quantum computer in seven years?!“

- The Motive Assassination: If you persist with questions, they abandon the scientific debate entirely and attack your character. “You’re just saying this because you have something to sell.” Or, “You’re a hype-man protecting your grant money.” In other words, impugn motives to invalidate the discussion.

These tactics aren’t designed to foster understanding; they’re designed to shut down the conversation. The cynic isn’t interested in the trajectory of the technology – they’re interested in adopting a posture of superiority. So, they substitute a cheap, easily deployed facade: a sneering, world-weary dismissal. It’s a costume they wear to project an aura of seeing through the “hype” that all us foolish optimists are apparently drowning in. It’s the intellectual equivalent of sitting in the stands and jeering at the athletes on the field – mistaking snide commentary for capability.

In the current climate of anti-intellectualism, anti-science sentiment, and social media echo chambers, this posture often works. In an anti-intellectual moment, saying “it’s all hype” can look braver than admitting “it’s complicated.” A convincing sounding cynic who questions the “establishment” and the science, can get likes and followers, even without ever providing a shred of evidence or even a rational thought. On social media, a crisp sneer will get far more engagement than a careful paragraph on, say, qubit noise bias or lattice surgery techniques.

To an uninitiated audience, dismissal can sound like discernment. The cynic often comes off as the only adult in the room, skeptically tempering the naive excitement of experts. But that supposed wisdom is a facade. By dismissing the entire field and impugning the motives of those within it, cynics relieve themselves of the burden of actually understanding it. And they do so while basking in unearned smugness.

Academic Cynicism in Disguise

Even more insidious is when cynicism dresses itself in the guise of rational, academic critique. We’ve seen professors – actual academics who should know better – gaining social-media clout by pointing out that quantum computers “haven’t factored any number larger than 21” or “haven’t achieved anything practical after decades of development.” This is cynicism with a bibliography: it has the appearance of a sober, fact-based argument, and it’s delivered from a position of at least some perceived authority, but it’s just as shallow. Claiming that the progress of the last decade predicts the progress of the next is intellectual laziness.

Yes, in 2025 quantum computers are still modest in their achievements. But the “nothing useful yet” argument betrays a profound misunderstanding of how science and technology progress. It’s the same short-sightedness that once led critics to dismiss emerging breakthroughs in other fields. The laser, for example, was famously dismissed in 1960 as “a solution looking for a problem.” Today lasers are essential to everything from surgery to telecommunications – indeed, to the very computers these cynics use to post their snark. Technology doesn’t develop in a linear, predictable way. Progress is often incremental for years, then explosive in a breakthrough; decades of “nothing” can precede a moment of everything.

This argument is the equivalent of someone in 1995 dismissing the internet because “after decades of development, it’s still mostly text.” Or someone in 2010 mocking deep learning because “neural networks have been around since the 1950s and still can’t drive a car.” We saw this viscerally with AI – decades of “winters,” then suddenly, systems that revolutionized entire industries.

Did the first transistor prove we’d never have a smartphone? Did the first block of the Bitcoin blockchain prove a decentralized digital currency was impossible? Of course not. Every transformative technology looked limited or impractical in its infancy – right up until it changed the world. Human flight pioneers were mocked. In 1903, the New York Times predicted that it would take humans 1 to 10 million years to develop an operating flying machine. The Wright Brothers did it 69 days later.

These kinds of cherry-picked snapshots (factoring 21, in this case) are like declaring a marathon over after the first mile, simply because the finish line isn’t yet in sight.

True intelligence in this space requires nuance. It requires the ability to hold two competing ideas in your head at once: that formidable, real engineering challenges remain, AND that the pace of progress is staggering and has consistently defied old predictions. The goalposts for “usefulness” in quantum computing are already moving. Noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, despite their imperfections, are today being used to simulate quantum chemistry and materials in ways that push beyond classical methods. An intelligent perspective can acknowledge the remaining hurdles and the hype, while still recognizing the profound potential and the steady, measurable advances being made.

The Real Cost of Cheap Cynicism

This cynical posturing wouldn’t matter if it were just irritating theater. But cynicism has real costs. It shapes public perception, skews funding decisions, and can discourage the next generation of researchers. I’ve seen brilliant students hesitate to pursue quantum computing because the online discourse is so dominated by voices loudly declaring it a dead end. I’ve watched policy makers, unable to distinguish informed skepticism from empty cynicism, grow hesitant to support quantum research after hearing one too many confidently dismissive takes.

Cynics will tell you they’re providing a valuable service, acting as a counterweight to hype. But there’s a crucial difference between the skeptic who says, “These specific technical challenges need to be solved,” and the cynic who smugly pronounces, “This will never work,” without providing a shred of technical rationale. One advances the field by identifying obstacles to overcome; the other simply performs an unearned air of profundity for an audience. When cynics dominate the discourse, genuine inquiry gets replaced by performative doubt. It creates a climate where saying “it’s all hype” drowns out any discussion of why it’s hard or how it might still succeed. Cheap cynicism, in other words, can stifle the very progress it claims to critique.

Skepticism vs. Cynicism: Know the Difference

It is crucial not to confuse the cynic with the skeptic. We need skepticism. A skeptic is vital to the scientific process. A skeptic engages with the facts, demands rigor, and adjusts their viewpoint based on evidence. They might say, “Your claims about this new qubit’s performance are interesting. Is the manufacturing process scalable? What about the error-correction overheads?” A skeptic poses falsifiable claims and earnest questions. They want to get at the truth.

A cynic, by contrast, has already reached a conclusion – often based on a mix of knee-jerk pessimism and presumptions of bad faith. A cynic might say, “I don’t care what your data shows; the whole field is a scam. It will never scale.” Cynicism is impervious to evidence. Skepticism is a function of intelligence; cynicism, as Lynes noted, is its substitute.

Use this quick field guide when a spicy hot take crosses your feed:

- A skeptic…

- States a falsifiable claim or specific prediction (e.g. “Given X noise model, achieving Y error rate would require Z physical qubits“).

- Cites numbers, peer-reviewed papers, or roadmaps – and is willing to update or correct these references when new data comes in.

- Acknowledges uncertainty and distinguishes near-term NISQ limitations from long-term fault-tolerant goals.

- Can steelman the other side’s best argument (i.e. can articulate the strongest case for the technology even if they doubt it).

- A cynic…

- Makes absolute pronouncements with no clear mechanism or supporting data (“Quantum X will never work, period“).

- Substitutes attacks on motives for actual analysis (“Everyone in the field is a grifter or deluded“).

- Shifts the goalposts as evidence accumulates (when one milestone is met, dismisses it and demands another, always redefining “useful” to exclude any current achievement).

- Equates pessimism with profundity, as if expecting failure is inherently more savvy than hoping for success.

Moving Forward: Embrace Skepticism, Reject Cynicism

Building a quantum computer is arguably one of the hardest things humanity has ever attempted. The timelines are uncertain and the engineering challenges are immense. It will require serious people doing serious, painstaking work, often over many years before results pay off. If you encounter someone casually dismissing the entire field out of hand, challenge them to engage on substance. Ask why they think progress will stall. Ask for their technical rationale or which research results inform their certainty. What you’ll usually find is that their cynicism is a shield – a way to avoid confronting complexity. It’s far easier to mock the effort than to contribute to it, or even to understand it.

Don’t mistake the noise of cynicism for the signal of intelligence. If someone validates themselves as a useless cynic – unwilling to provide anything beyond scoffs and derision – don’t waste your energy getting dragged into their performative pessimism. Instead, direct your attention to the genuine skeptics and curious contrarians who challenge ideas in good faith. Engage with those asking hard questions and with the enthusiasts pursuing big dreams (but grounding them in data). Those are the debates worth having.

That said, it can sometimes be worthwhile to engage with cynics – not for their sake, but for the undecided readers observing the exchange, in the hope they will see through the performance when it’s pointed out.

The field of quantum computing is built on the terrifyingly difficult work of bending reality to our will, one qubit at a time. That work deserves better than a cynical sneer. It deserves genuine, rigorous, and yes – critical – intelligence.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.