Quantum-as-a-Service (QaaS)

Table of Contents

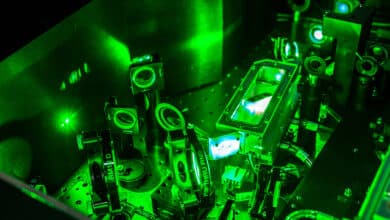

Imagine logging into a cloud platform and running complex quantum algorithms on exotic hardware located miles away, all within minutes and with just a credit card. This scenario is no longer science fiction – it’s the reality of Quantum-as-a-Service (QaaS).

Much like how cloud computing revolutionized access to classical computing power, QaaS is democratizing quantum computing by delivering it via the cloud. Instead of investing millions in a fragile quantum mainframe on-premises, companies can now “rent” time on quantum processors hosted by providers.

What is Quantum-as-a-Service (QaaS)?

Quantum-as-a-Service (QaaS) – also called Quantum Computing as a Service (QCaaS) – is essentially cloud-based access to quantum computing resources. In simple terms, a third-party hosts quantum computers (and related software tools) in the cloud, and users access those quantum capabilities remotely over the internet. This model parallels other “as-a-Service” offerings like Software-as-a-Service or Infrastructure-as-a-Service. The cloud provider handles the complex quantum hardware and software stack, and users can run their quantum algorithms or experiments via a web portal, API, or integrated cloud platform – without needing to own or maintain any quantum hardware themselves.

It’s hard to overstate how significant this is. Quantum computers are remarkably delicate and expensive machines – typically housed in specialized labs with extreme refrigeration (near absolute zero) and isolation from noise. Until recently, only a few large organizations or research labs could afford to build and operate them. QaaS breaks down this barrier by allowing time-sharing of quantum hardware similar to how timesharing on mainframes worked in the 1960s. In fact, many observers draw an analogy: early quantum computers in cloud data centers are “like the mainframes of the 1960s”, requiring large cryogenic systems and special environments, so offering remote access makes practical sense.

The concept took off notably when IBM put a small 5-qubit quantum processor online in 2016, as part of the IBM Quantum Experience. This bold move – offering a quantum computer to the public via the cloud – “sparked a whole ecosystem” of quantum computing research and development. Thousands of researchers, students, and companies started experimenting, leading to “thousands of papers” and proof-of-concept projects that would not have been possible otherwise. IBM’s early cloud quantum service essentially democratized access, proving that even nascent quantum technology could be shared broadly and securely over the internet. Following IBM’s lead, other tech giants and startups rushed to offer their own cloud-based quantum platforms.

Today, QaaS generally works like this: a user logs into a platform (for example, IBM Quantum, Amazon Braket, Microsoft Azure Quantum, etc.), writes a quantum program using a software toolkit or web interface, and submits it to run on a chosen quantum processing unit (QPU) or a simulator. The job gets queued and eventually executes on the remote quantum hardware, and the results are returned to the user’s environment. Virtualization and cloud orchestration hide the complexities – users don’t have to worry about calibrating qubits or maintaining cryogenics. Some QaaS platforms even provide full development environments, pre-built algorithms, and high-level libraries so that users can work at a more abstract level. Pricing can be pay-as-you-go (PAYG) – for instance, paying per quantum job or per “shot” (execution) – or via subscription plans for a certain number of runs or dedicated priority access. In some cases, customers can reserve exclusive time on a quantum machine for a hefty fee, which guarantees priority and avoids long queues. The goal is flexibility: use quantum resources on-demand, just like cloud servers, without the upfront investment.

Why is this important? QaaS lowers the barrier to entry for quantum computing dramatically. Organizations that are curious about quantum’s potential no longer need a team of PhDs and a multi-million-dollar lab to get started. They can experiment by leveraging cloud-hosted quantum computers, much as a startup might use AWS instead of buying its own data center. In the words of IonQ’s CEO Peter Chapman, “making quantum computers easily available to anyone via the cloud demonstrates that quantum is real, because now anyone can run a quantum program with a few minutes and a credit card”. This “democratization of access is core to realizing the promise of quantum,” Chapman emphasizes. In other words, wide access will spur innovation – perhaps “a kid in a garage” will discover a killer app for quantum because they could play with a cloud quantum computer.

Why Use Quantum Computing via the Cloud?

For most enterprises, QaaS is the only practical way to dip into quantum computing today. The reasons mirror the general benefits of cloud computing, but are even more pronounced given quantum’s current state:

Avoiding Astronomical Hardware Costs

A commercial quantum computer is extremely costly to build and maintain in-house – “starting prices for a low-qubit system can easily reach $1 million or more” just to purchase, not to mention ongoing operations.

By contrast, accessing a cloud quantum service requires no capital expenditure. It converts a multi-million-dollar outlay into an operating expense – you pay only for the compute time you use. This lowers the financial risk for early adopters: a research team or innovation group can run trials on a quantum machine for perhaps a few thousand dollars, rather than convincing the CFO to invest seven figures up front. The pay-as-you-go model makes quantum experimentation “affordable” relative to the alternative.

Low Barrier to Experimentation and R&D

Because QaaS offers on-demand access, organizations of all sizes (even startups or university labs) can try out quantum algorithms and workflows. This accelerates research and prototyping. Teams can run small experiments to gauge if quantum might provide any advantage for a problem – be it optimizing a supply chain, simulating a molecule, or training a tiny quantum ML model – without a huge commitment. In essence, QaaS “democratizes” cutting-edge computational power that was once confined to elite labs.

Access to Cutting-Edge Technology

Quantum hardware is evolving rapidly. The machines available in 2023-2025 (say 20-100 qubits for gate-model systems, and 5000+ qubits for special-purpose annealers) will likely be outclassed by new generations in a year or two. If you buy a quantum computer, you’re stuck with that generation. But using QaaS means whenever a provider upgrades to a new processor, you get to tap into it immediately. For example, when IBM or IonQ or Rigetti release a new higher-qubit device or improved fidelity, it gets added to their cloud lineup – customers can run on the latest hardware without any new investment.

In a field where progress is fast, this “instant upgrade” advantage is huge. It also means providers handle all the tricky maintenance: recalibrating qubits, replacing failing components, mitigating noise – so users always experience the best the hardware can offer at that time.

Scalability and Flexibility

QaaS platforms let you scale your usage up or down easily. If you only need a few small runs, you might use a free tier or low-cost on-demand plan. If you suddenly need thousands of circuit executions for a bigger experiment, you can ramp up usage (subject to queue times) across multiple hardware backends. You’re not limited by owning one machine. In fact, many cloud platforms offer a variety of quantum backends – different technologies and qubit counts – under one roof (more on that in the next section). This allows users to choose the best fit or even compare results across devices. And since it’s all accessed via standard cloud endpoints, researchers can collaborate globally, accessing the same quantum resource from anywhere.

In short, QaaS scales to the user’s needs and supports global accessibility, which would be hard to match with a single on-prem quantum box.

Integration with Classical Computing and Tools

Cloud quantum services often come with rich software stacks and APIs that integrate with classical computing resources. For example, you might write a hybrid algorithm in Python that uses a classical optimizer on your laptop or cloud instance, and calls a quantum subroutine via an API. QaaS providers supply SDKs (software development kits) that work in familiar languages like Python, and even plugins for workflows like Jupyter notebooks. Some offer pre-built algorithm libraries (e.g. for optimization or chemistry) so you don’t have to start from scratch. This means you can incorporate quantum computing into your existing data science or HPC workflows more easily.

In cloud environments, it’s also easier to pipe results between classical and quantum services. For instance, AWS’s Braket service allows running a “hybrid job” where a classical instance in the cloud coordinates iterative calls to a QPU, keeping the loop close to the hardware to reduce latency. We’ll discuss integration in detail later, but suffice it to say, QaaS can simplify linking quantum with your IT infrastructure – no need to wire up an on-prem quantum device to your network or write low-level drivers.

Rapid Innovation and Collaboration

By having many users on a shared platform, QaaS fosters a community. Providers often have tutorials, forums, and even experts available to help. For example, some services include access to quantum scientists or solution consultants who guide users in formulating problems or optimizing circuits.

The cloud model also encourages standardization of interfaces – e.g. a common open-source framework like Qiskit or Cirq can be used to target multiple cloud backends – which in turn lets academia and industry more easily share knowledge. It’s no coincidence that many breakthroughs in quantum algorithms or demonstrations (from variational algorithms to error mitigation techniques) were done on cloud-accessible quantum computers – the accessibility invites more minds to contribute. In other words, developers can tinker with quantum using tools they’re familiar with, which spurs creativity.

In summary, QaaS hugely reduces the financial, logistical, and expertise hurdles that would otherwise bar most companies from touching quantum computing. It’s an on-ramp to the quantum era, letting enterprises focus on what they want to try with quantum, rather than how to build a quantum computer. As a result, cloud-based quantum experimentation is enabling real use cases far sooner than if everyone waited to own their quantum machine. Material science companies, banks, automakers, pharma labs – all are testing quantum algorithms via QaaS (as we’ll see with examples) precisely because the cloud made it feasible.

Before diving into those real-world examples, let’s map out the current QaaS landscape – who are the major providers and what exactly they offer today.

The QaaS Landscape: Key Players and Offerings

The QaaS ecosystem in 2025 comprises both dedicated quantum hardware companies offering cloud access to their machines, and large cloud providers integrating quantum services into their platforms. Here are the key players (both present and emerging) in the Quantum-as-a-Service arena:

IBM Quantum

IBM was a pioneer in cloud quantum access. The IBM Quantum Platform (accessible via IBM Cloud and the IBM Quantum Network) provides access to IBM’s fleet of superconducting quantum processors. IBM now has systems ranging from modest 5-qubit devices for free users up to advanced 127-qubit and 433-qubit processors (with names like Eagle and Osprey) for enterprise and research clients. Users program these via IBM’s open-source Qiskit framework.

IBM offers a tiered model: a free tier for smaller machines and simulators, a pay-as-you-go tier for larger systems, and premium plans (or partnerships) for priority access and the very latest machines. IBM even allows reserved time slots for dedicated use (essentially renting the machine by the hour, for a price).

Notably, IBM has also deployed on-premises quantum systems for a few partners (such as national labs and universities), but the vast majority of its 400,000+ quantum users access the hardware via cloud services. IBM’s QaaS includes a full development environment, educational resources, and recently a Qiskit Runtime that lets users run hybrid algorithms with classical co-processing close to the quantum hardware for speed.

Amazon Braket

Amazon Web Services (AWS) launched Amazon Braket, a fully managed quantum computing service, in 2020. Braket is a unique aggregator model: it doesn’t build its own quantum hardware (yet), but instead provides a single cloud interface to several third-party quantum devices. Through AWS Braket, users can access superconducting qubit processors from Rigetti, ion-trap devices from IonQ and Quantinuum, superconducting processors from Oxford Quantum Circuits (OQC) and QuEra’s neutral-atom system, as well as D-Wave’s quantum annealer – all through a unified SDK and on AWS infrastructure. Amazon handles the job queuing and billing, while the hardware resides in partner labs (or in some cases, AWS data centers via partnerships).

Braket also offers high-performance simulators for testing circuits (like state vector and tensor network simulators) and a feature called Braket Hybrid Jobs which runs a classical container alongside the QPU for iterative algorithms. Pricing on Braket is pay-per-shot or per-task, varying by device – e.g., ~$0.30 per quantum task on some machines, or hourly rates from ~$2,500 to $7,000 for reserved QPU time. AWS’s advantage is deep integration with its cloud ecosystem – you can use AWS identity, storage, and workflow tools with Braket.

Essentially, Amazon Braket is a one-stop quantum shop on the world’s biggest cloud platform.

Microsoft Azure Quantum

Microsoft’s Azure Quantum is another cloud hub for quantum services, integrated into the Azure cloud. Azure Quantum provides access to multiple hardware backends: currently, ion-trap QPUs from IonQ and from Quantinuum, as well as superconducting qubit devices from partners (in the past, QCI’s photonic system and others have been announced). Users can choose their hardware and run jobs through the Azure portal or Azure’s APIs.

Microsoft also leverages Azure Quantum to offer its quantum-inspired optimization services and robust simulators. A unique aspect is Microsoft’s own Q# programming language and the Quantum Development Kit, which can be used to write algorithms that run on these backends or simulated ones. Azure Quantum emphasizes a “full-stack” cloud service: from writing code in Q# or Python, to resource estimation for future quantum machines, to executing on present hardware.

For now, Microsoft does not have its own quantum hardware available (its ambitious topological qubit research is still in the lab), but Azure is positioning itself as the go-to cloud for mixing quantum and classical workflows – something Microsoft calls “quantum-centric supercomputing” in the future.

Pricing on Azure Quantum is similarly pay-per-job (with Azure credits etc.), and they offer enterprise subscriptions for consistent use. Azure’s tie-ins with the Microsoft ecosystem (developer tools, Azure credits, etc.) make it appealing for companies already in Azure’s cloud.

Google Quantum / Google Cloud

Google is a major quantum player on the hardware research side (with its superconducting qubit devices that achieved the well-known “quantum supremacy” experiment in 2019). However, Google’s approach to QaaS for external users has so far been through partnerships. In 2021, Google Cloud added access to IonQ’s quantum computers via its Marketplace, making IonQ’s 11-qubit and later 23-qubit ion trap systems available to Google Cloud customers. Google has also partnered with D-Wave, offering D-Wave’s Leap cloud service through Google Cloud for certain customers. These moves signaled that Google Cloud sees value in being a distribution channel for quantum hardware, even as Google’s own cutting-edge 72-qubit (and newer) superconducting chips remain mostly in-house for research collaborations.

There have been indications that in the future Google will offer its own quantum processors “as a service” to select customers (especially as they build towards larger error-corrected devices). For now, though, Google’s public QaaS presence is indirect – through third-party hardware on its cloud marketplace – plus its open-source software framework Cirq and a lot of quantum AI research support for clients. We can expect that as Google’s hardware matures, Google Cloud will become another major QaaS provider in its own right.

D-Wave Leap

D-Wave is unique in this list because it offers a different model of quantum computing – quantum annealing – specialized for optimization problems. D-Wave’s Leap quantum cloud service provides real-time access to the world’s largest quantum annealers (currently 5000+ qubit Advantage systems) and hybrid solvers that mix quantum and classical techniques. D-Wave has been delivering its quantum computers to customers (like Lockheed Martin, Los Alamos, etc.) for years, but with Leap (launched in 2018) they opened up access to anyone via the cloud. Leap boasts 99.9% uptime and an environment where users can submit problems formulated in D-Wave’s problem languages (like the Binary Quadratic Model for annealing).

They also provide a hybrid workflow platform so that larger optimization problems can be partially solved with quantum, partially classical. Notably, D-Wave’s cloud is also accessible through AWS (as a integrated hardware on Braket) and some other clouds, but Leap is D-Wave’s own portal. Year-long cloud subscriptions for D-Wave via AWS Marketplace are around $70,000 per year for enterprise-grade access. D-Wave’s approach is quite practical – many of its users are pursuing things like traffic flow optimization, scheduling, and machine learning with quantum annealing, and D-Wave provides coaching via its LaunchPad program to onboard organizations onto quantum applications. In the future, as D-Wave also develops gate-model quantum computers, it’s likely those will appear on the Leap service as well, expanding the portfolio.

IonQ Cloud

IonQ is a leading startup (now a public company) building trapped-ion quantum computers. IonQ’s devices (named Harmony, Aria, etc.) have high-fidelity qubits and are fully connected, making them attractive for certain algorithms. IonQ makes its hardware available through all the big clouds (AWS, Azure, Google), but it also offers the IonQ Quantum Cloud directly to customers. IonQ’s cloud platform allows users to access their QPUs via a web console or API, and it is compatible with major quantum SDKs – meaning you can use Google’s Cirq, IBM’s Qiskit, or other frameworks to craft circuits for IonQ’s machine. This is part of IonQ’s philosophy of openness: they want developers to feel at home using whichever language and have IonQ as the backend. IonQ’s hardware currently is around 20+ high-quality qubits (with plans to scale to #AQ 64 by 2025, which roughly equates to a much larger number of physical qubits).

IonQ’s presence in QaaS is significant because they have been very aggressive in partnering – as Peter Chapman (CEO) highlighted, cloud partnerships are how IonQ reaches a broad user base, since “the inherent value of using the cloud is freedom of choice” to try different hardware. IonQ’s next-gen systems are expected to be accessible via these cloud channels as soon as they are operational. For a customer, IonQ’s direct cloud or via Azure/AWS doesn’t change the machine you get – it’s more about convenience of platform. Either way, IonQ’s trapped-ion QaaS is a key offering, known for very high two-qubit gate fidelities (~99.9%) and long coherence, which can be advantageous for certain computations.

Rigetti Quantum Cloud Services (QCS)

Rigetti Computing is another prominent player, known for superconducting quantum chips. Rigetti’s QCS is a cloud platform that integrates Rigetti’s quantum processors with classical computing infrastructure for hybrid computing.

In fact, Rigetti’s QCS was one of the first true quantum cloud platforms (launched around 2017-2018), enabling clients to spin up a dedicated quantum virtual machine that included both a quantum chip and a co-located classical processor for running hybrid algorithms. Rigetti’s QCS provides APIs for embedding quantum calls into applications via the cloud. They also open-sourced a lot of their tooling (like PyQuil and the Quil language for quantum circuits).

Today, Rigetti’s latest generation chips (Aspen series, with ~80 qubits in a multi-chip arrangement) are available through QCS and also via AWS Braket. Rigetti emphasizes ease of integration: their cloud service allows an HPC or enterprise user to, for example, connect their high-performance classical compute to Rigetti’s QPU over the network with minimal latency. Think of it as a quantum coprocessor in the cloud that your application can call. Rigetti’s roadmap includes scaling to larger, more error-corrected processors, which presumably will slot into QCS.

They also offer a “Quantum Advantage Program” for partners to work closely with Rigetti on applications via the cloud access. While Rigetti has faced some technical and business challenges recently, it remains one of the few with a vertically integrated QaaS (own hardware + cloud stack).

Quantinuum (Honeywell)

Quantinuum is the company formed by the merger of Honeywell Quantum Solutions (hardware) and Cambridge Quantum (software). Honeywell’s machines (using trapped-ion technology like IonQ, but different architecture) are branded H1 and H2. Quantinuum makes its H-series quantum computers available via Microsoft Azure Quantum (as one of the hardware options), and also offers direct cloud access for certain customers and research partners. Through Azure, users can run on H1-1 or H1-2 devices, which currently offer up to 20 high-fidelity qubits with unique features like mid-circuit measurement.

Quantinuum also provides a suite of quantum software, including an advanced quantum compiler (t|ket>) and tools for specific domains (cybersecurity, chemistry, etc.), which can be used in conjunction with their hardware. While Quantinuum’s cloud footprint is a bit less “self-service” than IBM/AWS (since most use is routed through Azure or their own agreements), they are considered a top-tier hardware provider. For example, they demonstrated high-fidelity quantum volume records, and their devices are used for cutting-edge experiments in error correction. Any enterprise using Azure can simply select Quantinuum’s backend and run jobs, so in effect Quantinuum is a key part of the QaaS fabric via its partnerships.

Xanadu Cloud (Photonic QaaS)

Xanadu is a startup pioneering photonic quantum computing (using light rather than matter for qubits). Xanadu’s X-Series quantum processors (e.g. X8, X12) were among the first photonic QPUs deployed to the cloud. Xanadu’s cloud allows researchers to run quantum programs on their chips via a platform called Strawberry Fields (for photonic circuit programming).

In 2022, Xanadu made a splash by unveiling Borealis, a photonic quantum computer that achieved quantum advantage in sampling, and made it available to the public through their cloud. This marked the first time a photonic machine of that scale was accessible as a service. Photonic QaaS is especially interesting because the hardware can be pulse-powered and potentially scaled via optical networks. Xanadu’s approach is to let users submit jobs for either streaming mode photonic processors or batched circuits. This broadens the technology choices in QaaS beyond the typical superconductors and ions. Photonic devices might, for certain tasks, eventually allow very large numbers of effective qubits, so having them on the cloud now is exciting for experimentation.

The Xanadu cloud is likely the first of many photonics-based QaaS offerings, with others (like PsiQuantum, discussed below) on the horizon.

Emerging Players (Future QaaS)

Beyond the current platforms, many companies plan to offer powerful quantum computers via cloud or hybrid models in coming years.

One notable example is PsiQuantum, a well-funded startup aiming to build a million-qubit fault-tolerant photonic quantum computer. PsiQuantum is designing its machines to be deployed in existing data centers (they have partnerships with data center operators) – implicitly, their model is to deliver quantum power through cloud/data center integration, rather than selling boxes one by one. If PsiQuantum achieves its goal in the late 2020s, we might see their million-qubit photonic quantum computers accessible as a service for enterprises (likely through partnerships with cloud providers or direct service to large clients).

Another up-and-comer is IQM (Finland), which is building on-premises quantum systems for supercomputing centers now, but also launched a cloud service called “Resonance” for remote access to their test devices.

Quantum Inspire (Europe’s cloud quantum platform from TU Delft) is providing access to a small superconducting device and a silicon spin-based device for researchers – a sign that more academic and national programs will stand up QaaS portals. Companies like Oxford Quantum Circuits (OQC) have an 8-qubit device “Lucy” that was available on AWS Braket, and they are working on next-gen processors which will likely appear on cloud platforms. QuEra Computing (neutral-atom QPUs) offers its machines like the 256-qubit analog quantum processor Aquila on Amazon Braket and also has premium cloud access and on-prem options for customers.

As quantum hardware evolves, we expect new QaaS offerings from players like: European national initiatives (e.g., France’s Pasqal’s neutral-atom QPUs likely via cloud), Japanese efforts (Toshiba’s quantum sim and others), and even companies like NVIDIA, which is exploring quantum-classical integrated systems. The trend is clear: any significant quantum computer developed will be accessible remotely, because that’s the only way to economically share these rare machines with those who need them.

It’s also worth noting a growing ecosystem of software-focused startups providing QaaS platforms. Companies like Strangeworks, QC Ware, Zapata, Classiq and others do not necessarily build their own hardware; instead, they offer cloud-based software platforms that aggregate multiple quantum hardware backends and provide user-friendly interfaces or high-level algorithm services. For example, Strangeworks has a platform where users can write code and run on IBM, IonQ, and others through one interface; QC Ware’s Forge platform allows users to solve specific problems (like optimization, chemistry simulations) and under the hood it decides whether to use a quantum backend or classical solver. These aren’t “quantum computers” as a service per se, but rather “quantum software as a service” running atop the hardware QaaS. They are relevant for enterprises because they further abstract quantum computing into something like a problem-solving cloud API.

With all these players, one might ask: is anyone actually using QaaS beyond playing around? The answer as of mid-2020s is yes – albeit for mostly exploratory and pilot projects. Let’s look at some real-world examples of how organizations are integrating QaaS into their work, to give a concrete sense of its applications.

Real-World Use Cases and Early Adopters

Even in this early stage, forward-thinking companies across industries have been experimenting with QaaS to tackle certain problems or to build quantum skills. Most of these are pilot projects or research efforts (since quantum computers are not yet outperforming classical computers at scale in practical tasks), but they are important in proving the concept and preparing for a quantum-enabled future. Here are a few illustrative examples and stories:

Traffic Flow Optimization – Volkswagen (Automotive)

One of the early headline cases was Volkswagen’s experiment to optimize taxi routes in Beijing using a quantum algorithm. Volkswagen used D-Wave’s quantum cloud service to run a traffic flow optimization algorithm that could compute the optimal routing for a fleet of taxis to reduce congestion. By leveraging D-Wave’s annealing QPU (accessible through the cloud), they encoded a traffic optimization problem (a variant of the notorious “travelling salesman problem”) into a form solvable by quantum annealing.

The result was a proof-of-concept that a quantum approach could coordinate traffic lights or vehicle routes more efficiently. While a classical system can also handle such tasks at current scales, the project demonstrated how QaaS allowed Volkswagen to tap into quantum computing without building any hardware.

A classical computing team could experiment with quantum algorithms simply by accessing D-Wave’s Leap service from their existing IT environment. It’s a prime example of an industry (automotive mobility) exploring QaaS for future smart city solutions.

Material Science and Chemistry – Bosch (Manufacturing) & Biogen (Pharma)

Quantum computers are theoretically very good at simulating molecular systems, which is critical in materials science and drug discovery. Companies have started trying these applications via QaaS. Bosch, the engineering and technology company, used IBM’s quantum cloud to simulate new materials for energy storage – essentially looking at novel battery materials and chemical reactions. By running quantum chemistry algorithms on IBM’s superconducting qubits, Bosch aimed to gain insights into molecular interactions that are hard for classical computers to simulate exactly.

Similarly in pharmaceuticals, Biogen tapped Microsoft’s Azure Quantum service to accelerate aspects of drug discovery and development. With Azure’s QaaS, they could run quantum-inspired algorithms or small quantum circuit experiments for things like protein folding or chemical reaction dynamics. While these simulations are still small in scale (due to limited qubit counts), they let companies validate methods on real quantum hardware. One pharma experiment combined classical compute with an IonQ quantum chip (via Azure) to test a quantum machine learning model for drug molecule properties. The key is that cloud access made collaboration easy – in Biogen’s case, they worked with Microsoft and consulting firm Accenture via the Azure cloud, each bringing expertise to the table.

Financial Portfolio Optimization – JPMorgan Chase (Finance)

JPMorgan has been very active in quantum computing research, primarily through IBM’s Q Network (IBM’s quantum cloud partnership program). They have experimented with quantum algorithms for portfolio optimization, option pricing, and risk analysis. In a notable milestone, JPMorgan (with IBM and other partners) demonstrated a quantum speedup in generating high-quality random numbers for cryptography by running protocols on Quantinuum’s trapped-ion machine through the cloud.

The ability to do this via QaaS meant the bank’s researchers didn’t need to own the exotic hardware; they could simply call cloud routines and focus on the financial math. Banks and hedge funds are using QaaS as a sandbox for potentially high-value algorithms (like finding arbitrage opportunities or optimizing trading strategies), so that they are ready to deploy them when quantum hardware becomes powerful enough to give an edge.

Supply Chain and Logistics – DHL and South Korea’s Customs (Logistics)

Optimization problems abound in logistics – from routing delivery trucks to scheduling shipments through a supply network. DHL has partnered with quantum startups to use QaaS for route optimizations, trying both D-Wave’s annealer and gate-model machines via cloud platforms to see if they can improve on classical solutions for complex delivery routing.

Another example: quantum startups worked to optimize container loading and customs inspection schedules, using an annealer accessed through the cloud to crunch this combinatorial problem that involves many constraints.

These projects illustrate that QaaS allows testing quantum approaches on real operational problems – sometimes the results show quantum isn’t yet better, but sometimes they yield new heuristics that improve classical methods. Either outcome is valuable, and it’s only feasible because cloud access made it relatively easy to try quantum on these industry problems.

Research and Academia – Thousands of Users

Outside of corporations, QaaS has opened quantum computing to university students, professors, and individual researchers worldwide. For example, a college student in India or Slovenia can log onto IBM Quantum Experience and run an experiment on a 7-qubit machine to test a new algorithm idea. This was unheard of a decade ago. As a metric, IBM reports over 400,000 users on its quantum cloud, running billions of circuits every day (many of those on simulators, but a significant number on real devices).

Academic groups have used QaaS to perform landmark experiments: e.g., demonstrating new error correction techniques on IBM or Quantinuum hardware, or benchmarking the performance of algorithms like Shor’s or Grover’s on various platforms. In one case, dozens of universities collaborated through the cloud on IBM’s 127-qubit processor to study quantum simulation of a material – coordinating via QaaS since none of them could host such a machine locally.

This broad accessibility means the talent pool training on quantum is growing fast, which benefits industry too. We are essentially crowdsourcing quantum R&D globally via cloud access, accelerating the progress of the field.

These examples underscore a common theme: QaaS is enabling practical exploration and “quantum-readiness” without requiring quantum hardware ownership. Companies like Volkswagen, Bosch, JPMorgan, etc., have clear business-driven goals (optimize traffic, design better batteries, improve financial models), and they see quantum computing as a potential tool. By leveraging QaaS, they can start the journey now – develop algorithms, gather expertise, identify challenges – so that as hardware improves, they will be ready to deploy quantum solutions competitively. In the words of IBM’s quantum lead in Germany, “Bosch… have a clear business objective in mind” for using quantum – even though current work is a proof of concept, they are building capability for the future.

It’s worth noting that nearly all these projects remain exploratory. We are in the era of “quantum advantage” experiments, but not yet broad quantum supremacy in real-world tasks. For most companies, using QaaS today is about learning and preparing. QaaS makes that feasible and relatively low risk.

Now that we’ve seen why and how organizations are using QaaS, an important practical question arises: how do you actually integrate these cloud quantum resources into your existing computing workflows? Specifically, if you have HPC (high-performance computing) infrastructure or on-prem systems, how can QaaS be combined with them effectively? We address that next.

Integrating QaaS into HPC and On-Prem Workflows

Enterprise IT and scientific computing environments are complex, and introducing quantum computing into the mix presents both opportunities and challenges. Most organizations will not use quantum computers in isolation – instead, they’ll use them as accelerators or specialized co-processors alongside classical systems. This leads to the concept of hybrid quantum-classical workflows, where part of a computation runs on classical HPC resources and part on a quantum computer accessed via QaaS.

The good news: QaaS is inherently remote and programmable, so in theory it can be integrated similar to how one might call an external API or spin up a cloud GPU for heavy computation. The reality: current HPC-quantum integration is in early stages, and there are hurdles like latency, software compatibility, and scheduling to overcome. Let’s break down the considerations and current approaches:

Quantum as an Accelerator (Conceptual Analogy)

Think of a quantum processor as a highly specialized accelerator, akin to a GPU or FPGA, that you call when needed. In HPC terms, one can envision quantum nodes available in a computing cluster. With QaaS, those “quantum nodes” are accessible via network calls.

For example, a classical program might reach a part of its algorithm that is extremely slow (NP-hard optimization, large matrix that needs sampling, etc.) Rather than grind through classically, the program could formulate a quantum circuit or annealing problem, send it to a QaaS endpoint, and receive the result to continue the computation. This is analogous to how HPC codes offload linear algebra to GPUs. Hybrid algorithms like VQE (Variational Quantum Eigensolver) or QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization) are designed this way – a classical optimizer iteratively updates parameters, and a quantum accelerator (via QaaS) evaluates a cost function for those parameters.

Many cloud providers now support this pattern by allowing a persistent classical process to run in the cloud close to the QPU – e.g., IBM’s Qiskit Runtime or AWS’s Braket Hybrid Jobs – which minimizes back-and-forth latency. This hybrid model is expected to be the backbone of quantum computing usage for years to come, combining the strengths of classical and quantum.

HPC Integration Projects

Leading supercomputing centers are actively experimenting with integrating QaaS into their workflows. For instance, the Jülich Supercomputing Centre (JSC) in Germany has a project called JUNIQ (Jülich UNified Infrastructure for Quantum computing), which provides users access to various quantum backends (including a local quantum annealer and remote gate QPUs) through the same interface they use for HPC jobs.

In one EU initiative, two quantum simulators (actual quantum devices acting as co-processors) are being co-located with HPC clusters – one at GENCI in France and one at JSC – to form a tightly integrated quantum-classical supercomputer. The project is developing a software “fleet” to manage code compilation, execution, and data flow between the classical and quantum parts.

The early lesson is that “no linux-like software exists for QC” yet – meaning each quantum device has its own stack – so integrating them requires custom middleware. HPC centers are essentially building the tooling to make a quantum job just another job in the queue.

Similarly, in the US, national labs like Oak Ridge and Lawrence Berkeley (NERSC) have programs to interface their supercomputers with cloud quantum services, and the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center has tested D-Wave’s QaaS for discrete optimization tasks. All this R&D is pushing toward standardized interfaces where an HPC scheduler can hand off a subtask to a quantum service seamlessly.

Latency and Co-Location

One big integration challenge is latency – the time it takes for data to travel to the quantum processor and back. If your quantum job is small and requires only a single round-trip (send input, get answer), this latency (maybe tens to hundreds of milliseconds over the cloud) is usually not an issue. But if your algorithm requires many iterative calls (like thousands of quantum circuit evaluations in a loop), network latency can become a bottleneck.

There are a few solutions:

- Co-locate classical and quantum resources as much as possible, e.g. running your classical driver program on a cloud server in the same data center or region as the QPU to cut round-trip time (this is precisely what AWS and IBM are doing with their hybrid job solutions).

- Batching or vectorizing quantum calls so you send one big job that executes multiple sub-tasks on the QPU in sequence without additional communication (some platforms allow sending a “batch” of circuits to be run, reducing overhead).

- In the future, physically co-locating quantum hardware with supercomputers – for example, having a quantum machine installed on the same network or even the same rack as an HPC cluster. In fact, IBM has discussed the vision of quantum and classical processors eventually sitting side by side (or even on the same chip someday) for extreme low-latency integration.

While we’re far from on-chip integration, there are already instances of on-prem quantum nodes: JSC has a small superconducting QPU on-site and Finland’s VTT has an Helmi quantum computer integrated with a local supercomputer.

The rule of thumb is: if an application requires millisecond-level feedback between quantum and classical (for example, quantum error correction with real-time feedback, or certain variational algorithms that need immediate processing of results), co-location or specialized networking is needed. If latency isn’t critical (e.g. each quantum job is heavy compute but you don’t need the answer instantaneously), then cloud QaaS integration over standard internet is fine. Many HPC tasks like large batch jobs can tolerate seconds or more of latency, so they can call cloud quantum without issue.

Workflow Orchestration and Scheduling

Integrating QaaS also means fitting it into existing job scheduling and workflow management systems. In HPC environments, batch schedulers like Slurm, PBS, or IBM LSF manage jobs. These systems are now being extended to handle quantum requests. The idea is that a scheduler could query the QaaS for available QPUs (matching the required number of qubits), automatically select the least-backlogged device, run the circuit, and then pass the results back to the next stage. The future of HPC is in convergence of classical and quantum with workflows spanning both to solve complex problems.

Data Transfer and Security

When integrating on-prem or HPC systems with QaaS, data management and security considerations come in. Often the data quantum algorithms deal with isn’t massive (a set of parameters, or small input sets encoded in qubit states), so bandwidth isn’t a big problem. But if your use case did involve large data – say using a quantum algorithm for big data analysis – you’d have to send chunks to the quantum service, which could be slow.

In terms of security, sensitive data might need to be encrypted in transit to the QaaS (standard TLS encryption covers this in most cloud APIs). There’s also the concern of sending proprietary algorithms to an external service – companies might worry about code secrecy.

Generally, QaaS providers contractually protect user IP and don’t retain circuits or data beyond execution, but enterprises should perform risk assessments. In high-security environments (like defense or certain finance), the integration might require private dedicated connections (e.g. AWS Direct Connect or Azure ExpressRoute) to the quantum data center to avoid sending data over the public internet. Indeed, this ties into the earlier mention that sectors with extreme security needs might prefer on-prem quantum – but short of that, private network links to cloud quantum could be a compromise.

Standards and Interoperability

Today each QaaS has its own APIs, job definition formats, and software kits (though many support common frameworks like Qiskit or Cirq). For HPC integration, there’s a push for standardization – perhaps via projects like OpenQASM or Quantum IR (Intermediate Representation) to express quantum programs in a hardware-agnostic way.

The hope is that an HPC workflow manager could use a standard descriptor for a quantum job, which gets routed to an available QaaS provider that supports that standard. Some initiatives like the Quantum Intermediate Representation Alliance (led by Microsoft’s QIR) are looking to define such standards so that quantum programs can be portable across backends.

Until then, integrating multiple QaaS into one workflow can be clunky – e.g., you might need different code paths for IBM vs AWS vs Azure. Over time, we expect common integration layers to emerge (perhaps driven by the Linux Foundation or cloud standards bodies) to allow more plug-and-play quantum services in enterprise software.

In summary, connecting QaaS to your HPC or on-prem environment is very doable, but not yet turnkey. It often involves custom code or scripts, careful consideration of latency, and perhaps working within the provider’s cloud environment to get the best performance. But progress is steady: the Jülich and IBM examples show that within the next few years, launching a hybrid job that uses both HPC nodes and a quantum coprocessor might be as straightforward as any other distributed computing job. Organizations can prepare by containerizing quantum code and using APIs, so that switching between a local simulator and a remote QPU is just a configuration change.

One concrete way to start integrating is to use the provider’s cloud as the meeting point – for instance, run your classical workload on an AWS EC2 instance and have it call AWS Braket for quantum parts, rather than trying to call AWS Braket directly from an on-prem server (though that’s possible too). This way, you leverage the cloud’s low-latency internal network. Azure Quantum similarly provides Jupyter notebooks and cloud VMs that sit next to the quantum hardware for you. IBM’s Qiskit Runtime essentially gives you a container in IBM’s cloud where you can put your classical logic, so that it operates adjacent to the IBM QPUs. By designing your workflows with these hybrid capabilities in mind, you can start realizing the convergence of classical HPC and quantum that many see as the future of high-performance computing.

With integration strategies covered, let’s step back and consider bigger-picture comparisons: How does QaaS stack up against the alternative of buying or building your own quantum computer? And what about the emerging idea of Quantum Open Architecture where you mix and match components? The next section will compare QaaS vs. on-premises quantum vs. quantum open architectures (QOA), examining the trade-offs of each approach.

QaaS vs On-Premises vs Quantum Open Architecture (QOA)

As enterprises plan their quantum computing strategy, they essentially have a spectrum of choices:

- Use Quantum-as-a-Service (Cloud Quantum) – the model we’ve been discussing, where you access quantum hardware owned by a provider, over the internet. No onsite hardware, you pay for usage or subscription.

- Purchase/Install an On-Premises Quantum Computer (Monolithic) – buying a complete quantum system from a vendor and running it in your own facility (or a colocated datacenter). “Monolithic” here implies a single-vendor, integrated system – the typical case if you buy from, say, IBM or D-Wave.

- Build/Assemble a Quantum System via Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) – a more modular approach where you procure various components (quantum processor chips, control electronics, cryogenics, etc.) potentially from different providers and integrate them, possibly with the help of a system integrator. QOA isn’t about a specific machine, but rather a philosophy of constructing quantum computers using best-of-breed components, akin to how classical computing moved from proprietary mainframes to open architectures.

Each approach has advantages and disadvantages. Let’s compare them across key dimensions:

Deployment and Access

- QaaS (Cloud): Very quick to get started – you can sign up and get access to a quantum computer in minutes, as long as you have internet. It’s available to multiple users globally. However, access is mediated by the provider’s scheduling – you typically queue for a slice of time on shared hardware. If many users are on the service, you might wait in line (although providers offer priority tiers or dedicated reservations for a fee). There’s also the dependence on internet connectivity. For most non-time-critical tasks, that’s fine; but if your environment has to be air-gapped or cannot rely on external connectivity, QaaS might not fit by policy.

- On-Premises (Monolithic): Deployment is a major project – ordering a system (which could take months or more to fabricate), preparing a specialized room (quantum computers often need vibration isolation, extensive cooling infrastructure, etc.), and getting it installed by the vendor. Only a handful of organizations have done this. IBM, for example, delivered an IBM Quantum System One machine to the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany (in 2021) and one to Cleveland Clinic in the USA (2022), and these were huge efforts involving custom enclosures and continuous vendor support. Once on-prem, however, you have full control – the machine is dedicated to you. Access is immediate for your team; there’s no queue except your internal scheduling. For organizations that need guaranteed compute at specific times (e.g., daily batch job windows), having on-prem could ensure availability. On the flip side, very few companies have the facilities or expertise to house a quantum computer. It’s not just a server you rack; it’s more like having a sensitive lab instrument on-site.

- Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) / Custom-Built: This is really feasible only for advanced labs or consortiums right now. It means you might buy a quantum processor from one vendor (say a 50-qubit chip from QuantWare), a cryostat from another (e.g., Bluefors), control electronics from a third (Quantum Machines’ OPX), and integrate them. The benefit is flexibility and avoiding vendor lock-in – you can upgrade parts independently and choose the best components available. National labs are experimenting with this: for instance, in Germany, the Jülich center built a 10+ qubit quantum system using the QOA approach – they used QuantWare’s superconducting qubit chip and integrated it with other companies’ components. The Israeli Quantum Computing Center similarly integrated a QuantWare QPU with locally sourced control systems. If you go QOA, you essentially become your own integrator (or hire one). It’s a bespoke on-prem system. Access is like any on-prem – under your control. But expect heavy lifting in systems engineering and software development, because as noted, there isn’t yet a plug-and-play OS for quantum computers. Each QOA system might need custom drivers and calibration routines to get all components working in harmony. This approach currently is viable mainly for those who want to be on the cutting edge of building quantum hardware, not just using it. In the long run, though, QOA could lead to standardized, commoditized quantum components that many can integrate, analogous to assembling classical computers from CPUs, GPUs, etc.

Cost

- QaaS: It converts cost to operating expense. There’s no upfront capital cost for hardware, which is a huge advantage. But operating costs can accumulate. Cloud quantum is not cheap per unit of compute – for example, as cited, an hour on a quantum processor can cost thousands, and solving a large problem might require many such hours. There’s also often a cost for shots (individual circuit execution) – e.g., $0.00035 per shot on IBM for certain systems, which sounds tiny until you realize meaningful experiments may need tens of thousands of shots. If you ramp up usage significantly, you might find the cloud bills becoming substantial. However, until quantum computing delivers clear business value, few companies will saturate the QaaS to that extent. In practice, most treat it as experimental budget, tens of thousands per year at most, which is minor for an R&D division. Cloud also spares you maintenance and personnel costs – the provider handles those. So QaaS cost scales with your needs, which is ideal in this early phase. One caution: if a company anticipates very heavy, routine quantum workloads (say, running optimization jobs daily for production use), at some point renting might outstrip the cost of owning. But given hardware is evolving, many will stick with renting through a few hardware generations until the tech stabilizes.

- On-Premises: This is capital expense heavy. Buying an on-prem quantum computer (if a vendor will even sell you one – often they prefer cloud models themselves) can easily be in the millions of dollars for a modest system. For example, estimates have put a 20-qubit superconducting system with all its infrastructure at >$5-10 million including support. The maintenance and operation require specialist technicians (often PhD-level scientists) and significant power and cooling costs. So your operational expense is also high, effectively needing a mini quantum lab in your org. The upside is if you fully utilize the system over several years, the cost per use might be lower than paying per-shot on cloud. Additionally, some governments or agencies are willing to invest heavily in on-prem for strategic reasons (e.g. national capability building or data sovereignty). On-prem also gives cost certainty – once you buy, you’re not subject to cloud pricing changes or usage fees. But you’ll likely need periodic upgrades (which could mean buying a whole new machine in a few years as tech leaps forward). In short, on-prem is viable for those with big budgets and the need for dedicated use; otherwise, the TCO (total cost of ownership) is prohibitive for most in 2025.

- QOA / Custom-Build: Costs here vary widely. In theory, a QOA approach could be cheaper, especially in the future when multiple vendors compete on components. Today, though, it might be more of a “cost no object” research endeavor. You might save by sourcing a cheaper component or using an existing infrastructure (some unis have cryostats, etc.), but then you bear integration costs. QOA’s promise is economies of scale and specialization: companies focusing on one piece will drive that piece’s cost down, and you can assemble a solution cheaper than a vertically integrated vendor who does everything. We see parallels in classical computing: assembling a PC from parts is cheaper than buying a proprietary workstation. QuantWare, for instance, aims to sell superconducting chips “off the shelf” – a quantum CPU – and you could combine that with other components to make a full system at lower cost than an IBM might charge for a turnkey system. But we’re early on this curve. Right now, QOA is pursued mainly by government-funded projects where multiple companies collaborate to share costs and knowledge (essentially subsidizing the development of an open ecosystem). If QOA succeeds, it could significantly lower the cost of on-prem quantum in the future – maybe a mid-size enterprise could afford to assemble a quantum computer like they’d assemble a high-end HPC cluster. At present, that’s aspirational.

Performance and Innovation

- QaaS: Cloud providers currently offer the most advanced machines available (aside from secret lab prototypes). For example, IBM’s 127-qubit Eagle processor is accessible via IBM Q Network cloud, and their 433-qubit Osprey will be as well. These are beyond what any buyer can get on-prem at the moment. Cloud also allows quick adoption of improvements – if Rigetti refines its qubits or IonQ ups its qubit count, cloud users benefit immediately. On the other hand, QaaS users have limited influence over hardware configurations. If you want a custom configuration (say a specific qubit topology or a certain connectivity to test a theory), you can’t really get that from a standard cloud service. You get what the provider offers to all. For most, that’s fine. But for hardware R&D, cloud can be limiting. Also, performance consistency can vary; e.g., on a shared cloud QPU, calibration might drift or usage spikes could mean you get the machine at a slightly different calibration later (though providers work hard to maintain stability).

- On-Premises (Monolithic): You have the machine entirely for your use, which means you can potentially optimize how you use it more freely (run calibrations whenever, try custom pulse sequences if the vendor allows, etc.). But you’re limited to that machine’s capabilities until you upgrade hardware. If the rest of the world moves to, say, error-corrected qubits in 5 years and you have an older noisy quantum computer, you might fall behind unless you continuously invest. That said, on-prem might allow deeper experimentation at the hardware level if the vendor gives you low-level access. Some research institutions want on-prem specifically to tweak the hardware or integrate it with experimental equipment (like a specific sensor or novel cooling technique). Performance-wise, an on-prem IBM System One is identical to an IBM cloud system of the same model – but the on-prem user can run jobs back-to-back without waiting, which for large experiments can be a plus. Yet, if the hardware fails, on-prem means you wait for the vendor to fix it (possibly on-site), whereas cloud providers usually have many machines, so they can reroute jobs to a working one.

- QOA / Custom: Here is where innovation can flourish. If you build via QOA, you can incorporate the latest and greatest from multiple sources. For instance, you might use a cutting-edge control chip from Quantum Machines, a novel cryo infrastructure from Bluefors, and a qubit chip designed to your spec by QuantWare. This modular approach could accelerate innovation because specialists focus on each part. Also, if you are experimenting with different modalities (superconducting plus photonic links, etc.), QOA allows that mix-and-match. The performance of a QOA system could equal that of monolithic ones if done right – in fact it might surpass if you combine superior components. For example, a lab could replace an older qubit chip with a new higher-coherence one without replacing everything else, leapfrogging in performance. The obvious risk is integration issues might hinder reaching peak performance at all. But the general consensus in the industry, as even IBM’s Jay Gambetta noted, is that “the future is [not] a full-stack solution from one provider” – even companies doing everything now will likely embrace open architectures as complexity grows. The QOA approach is expected to drive standards and interoperability that eventually improve performance across the board. In effect, monolithic on-prem may be a transitional phase, and the ultimate on-prem model could become open-architecture.

Security and Compliance

- QaaS (Cloud): By using external cloud services, you inherently send data and computations off-site. For many, this is fine – cloud providers secure their systems well, and one can use encryption for data in transit. However, for highly sensitive data or regulated environments, cloud can be a concern. Industries like defense, government, critical infrastructure, or any handling classified data may not be allowed to use external quantum services for certain tasks. For example, a defense agency might explore quantum algorithms on public QaaS with dummy data, but they wouldn’t send actual classified data to a cloud QPU for security reasons. There’s also the angle of quantum computing in cryptography – ironically, a quantum computer powerful enough could break certain encryptions, but today’s QaaS are far from that, and anyway providers would not misuse them. Still, a CISO might worry about dependency: what if, say, all your critical quantum optimization runs happen on a third-party cloud and that cloud is unavailable due to an outage or geopolitical issue? In sensitive use-cases, these risks matter.

On the flip side, cloud providers often undergo certifications (ISO, SOC2, etc.) and can likely meet compliance for non-classified workloads (financial data, etc.) by ensuring data never persists and is isolated per tenant. We might also see “private QaaS” offerings – e.g., a cloud provider setting up a dedicated quantum machine for a customer accessible only via a private link. This is a hybrid of cloud and on-prem: the hardware is not on the customer’s site but also not shared with others. This model could address some security concerns while retaining provider management.

- On-Premises: Full control means potentially better security – data stays within your own infrastructure, and you can implement whatever access controls you want. For industries like banking or pharma worried about IP leaking, an on-prem quantum computer ensures that the only people running jobs on it are your people. Data sovereignty can also be a factor: some governments require that data processing happens within certain jurisdictions – owning the hardware can ensure compliance if, for example, using a foreign cloud is not permitted for some data. Additionally, having on-prem allows usage even if internet is down or if cloud services are cut off. This aligns with what a recent QuEra analysis noted: sectors with stringent data security needs (defense, government, sensitive IP) will likely prioritize on-premises quantum deployments to retain control and avoid data transfer risks. However, keep in mind, securing a quantum computer isn’t trivial either – you need to protect the control systems from intrusion, etc. A curious scenario: if quantum computers eventually can crack encryption, having one on-prem could itself be a security risk if an attacker got to it. But that’s a far-future hypothetical when QCs are much more powerful.

- QOA / Custom: This shares many of the on-prem traits since it results in an on-prem capability. One nuance: if you integrate components from various vendors, you have to trust all those pieces. For example, is the control electronics firmware secure? Is there any remote access needed for support? Those are concerns that a fully in-house system raises – but they are manageable with diligence. QOA could also allow incorporating post-quantum cryptography or custom security layers into the system design itself, since you control the stack. For instance, one could ensure that any network connection out of the quantum rack is encrypted with PQC algorithms so that even if someone tapped the lines, they get nothing useful. This level of customization is possible if you own the build.

Vendor Lock-in and Ecosystem

- QaaS: When using a cloud service, you can end up dependent on that provider’s ecosystem. If you develop a lot of software using IBM’s Qiskit and running on IBM Q, switching to another provider might require some porting effort (though many frameworks are similar). Interoperability is getting better: libraries like PennyLane or Qiskit can target multiple backends with minimal changes. But there is some stickiness – e.g., if you rely on specific features of one QaaS (like D-Wave’s hybrid solvers or IBM’s dynamic circuits), you can’t find those everywhere. Also pricing and terms could change – maybe a provider ups costs or discontinues a certain machine. In general, multi-cloud strategies can mitigate lock-in: some enterprises deliberately try a bit of IBM, a bit of AWS, etc., to stay flexible. We see this in classical cloud computing too. One lock-in breaker in quantum is the emergence of common intermediate representations: for example, Microsoft’s QIR and OpenQASM 3 aim to be standard program formats so you can deploy to any hardware supporting them. But until that’s universal, moving between QaaS platforms might require relearning new toolchains, which is a form of soft lock-in. The TechTarget piece explicitly notes “there’s a lack of standardization across QaaS offerings… toolkits from one provider look and work differently than another… seamless integration can’t be guaranteed; switching might require reintegrating and relearning a new platform.”. So this is a con of the nascent field.

- On-Premises (Monolithic): Here, you’re typically locked into the vendor you bought from, at least for that generation of hardware. If you bought an IBM system, you’ll be using IBM’s stack; if D-Wave, then D-Wave’s, etc. You might run third-party software on top, but the core hardware and control is proprietary. If you later want a different vendor’s machine, that’s a whole separate purchase. Some organizations hedge by having multiple on-prem quantum systems (like a national lab might have one of each type), but that’s extremely costly. One advantage though: if you own the machine, you might negotiate deeper custom collaboration with the vendor – effectively you become a close partner (like national labs do) which can guide the roadmap or get early insights. Still, monolithic on-prem is the definition of vendor lock-in, since only that manufacturer can support or upgrade it. This is one reason IBM and others advocate open architectures long term – even they acknowledge few will want to be chained to one vendor forever for something as strategic as quantum.

- QOA / Custom: The express purpose of Quantum Open Architecture is to break vendor lock-in and enable a multi-vendor ecosystem. Under QOA, standards and interfaces are established so that any compatible component can plug in. For example, if there’s a standard control interface, you could swap control hardware from one brand to another if it offers better performance. Or choose a different qubit technology down the line and still use your existing cryostat and control systems. QOA envisions best-of-breed components from multiple vendors integrating seamlessly. This fosters competition and innovation – similar to how in classical computing we have many companies specializing (Intel makes CPUs, Nvidia GPUs, others make motherboards, etc., all interoperable). We’re not there yet in quantum, but initial steps (like hardware-agnostic software frameworks, modular quantum computer designs, and consortiums setting interface standards) are underway. If successful, a QOA approach means an organization could upgrade or change parts without rebuilding from scratch, and not be beholden to one vendor’s full-stack roadmap. For enterprises, this flexibility could mean more bargaining power and a more diverse supply chain for quantum tech in the future.

Strategic Considerations – When to Choose What

The decision between these approaches will depend on an organization’s goals and constraints:

- If you’re just starting or only need occasional quantum runs – QaaS is the obvious choice. It offers lower barriers and pay-per-use. Early adopters almost universally go this route because it’s impractical to invest heavily until a clear quantum advantage is at hand.

- If you’re handling extremely sensitive data or must have full control – on-premises might be justified, if you can afford it. As a QuEra prediction noted, “industries like defense, government, and sectors handling sensitive IP… are likely to prioritize on-premises quantum deployments to retain control over data and avoid transfer vulnerabilities.”. Also, if you foresee constant high-volume quantum needs (say in 5-10 years, you run quantum jobs daily as part of operations), an on-prem system could be more cost-effective in the long run. However, given today’s hardware constraints, few have reached that point.

- If you are a research institution or tech company aiming to innovate in quantum hardware/software – you might pursue QOA or at least a partial on-prem combined with cloud. National labs are doing this to build expertise and shape the tech’s evolution. For a private enterprise, doing QOA might be too heavy a lift unless quantum computing is core to your business (currently, that’s rare outside of quantum startups themselves). But large companies (say in aerospace or telecom) could partner in QOA consortia to co-develop tech, gaining influence and early access.

It’s likely that, for the foreseeable future, a hybrid model will exist: Some organizations will indeed deploy on-prem quantum systems for mission-critical or high-security use cases, while the majority will rely on cloud QaaS for accessibility and scalability. We already see this pattern: for example, the U.S. government has an on-prem IBM quantum system (for dedicated research at Los Alamos), but many government researchers also use IBM’s cloud service for other work. A QuEra analysis predicts “by 2025, this dual deployment model will be a hallmark of the industry, with on-prem seen as essential for security-sensitive and high-frequency use cases, while cloud-based services continue expanding access and collaboration.”. Early evidence supports that: sectors like banking and pharma (less sensitive data) lean cloud, whereas something like a defense project or a national lab might lean on-prem when scaling up, for sovereignty reasons.

In comparing with QOA, it’s not so much QaaS versus QOA – they can complement. For example, a national lab could build a small QOA-based machine on-prem and also use external QaaS to access bigger machines or different tech. QOA is more about how you procure a quantum system (open vs closed) and could apply to both on-prem or to the cloud providers themselves (a cloud provider might internally use QOA to build their next quantum data center).

In summary, QaaS offers ease and quick access but with less control; on-prem offers control but at high cost and effort; QOA promises flexibility and innovation but is in nascent stages. Many organizations may start with QaaS, and only once quantum computing proves value, consider whether graduating to an on-prem solution (possibly built in an open architecture way) makes sense for them. It’s analogous to how many companies started in public cloud, and only some eventually bring workloads back on-prem when scale and stability justify it.

Now that we’ve covered almost every aspect – what remains is to gaze forward: How will QaaS evolve? What can we expect in the next few years from quantum cloud services and their role in enterprise IT?

The Road Ahead: The Future of Quantum-as-a-Service

Quantum-as-a-Service is still in its early days, but it’s poised to be the main delivery mechanism for quantum capabilities moving forward. For tech executives keeping an eye on quantum, several future trends and developments are worth anticipating:

More Powerful Hardware on QaaS

The obvious one – as quantum hardware improves, those improvements will manifest in QaaS offerings. We will see steady increases in qubit counts, better qubit quality (lower error rates), and new features like error mitigation and error correction layers on cloud-accessible devices.

IBM’s roadmap, for instance, aims for thousands of qubits with some level of error correction by 2026-2027; when that arrives, IBM will likely deploy those in their cloud first, before anywhere else. IonQ and Quantinuum plan higher numbers of logical qubits (via error correction) later this decade, delivered through cloud access. So enterprises using QaaS will seamlessly transition from today’s NISQ (noisy intermediate-scale quantum) devices to tomorrow’s error-corrected, larger systems. The end goal is a quantum cloud that feels almost like today’s cloud: you submit a job and get results with the quantum part being abstracted away. Achieving that means robust, stable hardware and software such that using a quantum service is as routine as calling an AI API today. We’re not there yet, but that’s the direction.

Serverless and Real-Time Quantum Cloud

Providers are talking about “serverless” quantum services. In cloud terms, this means you don’t even provision a specific QPU; you just submit a function or query and the cloud handles execution optimally across resources. For quantum, serverless could involve automatically choosing a suitable quantum backend, splitting tasks, or even using multiple QPUs in parallel if needed (quantum parallelization).

Real-time access improvements are also coming – already, some QaaS allow quasi-real-time tasks (e.g., feedback within a circuit up to certain latency). In the future, we might see quantum cloud services with 100% uptime SLAs, instantaneous routing to available QPUs, and maybe even multi-tenant quantum processing (where a big quantum computer is powerful enough to run more than one job at the exact same time through virtualization, though that likely awaits error-corrected machines). Companies like Amazon are already installing some QPUs in their data centers (e.g., OQC’s machine was physically hosted in AWS’s region). As quantum hardware stabilizes, expect cloud providers to integrate them more tightly into their infrastructure, improving reliability and reducing latency.

Convergence with Classical HPC and AI

We touched on integration – looking ahead, it’s likely that quantum computing will become another tier in the heterogeneous computing stack. Cloud platforms may offer composite services – for instance, an optimization service that under the hood uses classical solvers, GPUs, and quantum calls as appropriate. A user might not even explicitly call a QPU; they just call “solve this optimization problem” and the cloud service decides to dispatch some parts to a quantum computer if it’s beneficial. This is similar to how some cloud AI services use specialized hardware without the user dealing with it.

Quantum could become part of workflow templates for certain industries. For example, an end-to-end pharmaceutical cloud platform might incorporate quantum chemistry calculations via QaaS transparently when modeling a molecule.

As QaaS matures, domain-specific quantum-cloud solutions will emerge, and quantum computing will often work in tandem with AI and classical simulation. So, CIOs might find quantum computing creeping into their cloud workloads not as a standalone thing but as embedded capabilities within broader cloud offerings (possibly offered by third-party quantum startups via cloud marketplaces).

Industry-Specific QaaS Solutions

Building on the above, we may see Quantum-as-a-Service vertical offerings. For instance, a “quantum for finance” cloud solution could provide common algorithm templates for portfolio optimization, Monte Carlo risk analysis, etc., running on quantum backends. Or “quantum for logistics” offering solvers for routing problems that automatically use D-Wave or gate-model QPUs underneath.

Startups like QC Ware and others are already moving in this direction, essentially trying to package quantum algorithms into services that plug into existing enterprise software. As quantum hardware becomes more capable, the incentive to productize its unique capabilities grows. One could imagine AWS or Azure having a section in their cloud marketplace for quantum-accelerated applications – e.g., a quantum-enhanced machine learning model for supply chain forecasting, which the user can deploy without worrying about the quantum details (the service provider handles the QaaS behind the scenes).

This evolution would truly fulfill the promise of QaaS by making the quantum aspect invisible and focusing on the business problem.

Higher Level Abstractions and Software Progress

Another future aspect is the software and developer experience of QaaS. Today, using QaaS might involve writing quantum circuits at the level of gates or using domain-specific languages. In the future, expect more user-friendly abstractions. Think along the lines of drag-and-drop workflows, or quantum computing libraries integrated into common programming languages where quantum is just a function call. For example, there could be Python libraries where you call quantum_optimize(problem) and it automatically formulates and sends it to a QaaS provider.

These abstractions will be built on improved compilers and transpilers that can take high-level descriptions and target various quantum architectures optimally. The goal is to make quantum cloud usage as easy as calling any cloud API, so that even non-specialist developers can incorporate it when needed. This goes hand-in-hand with standardization.

Efforts like OpenQASM 3.0, QIR, and cloud API standards might converge such that code written for one QaaS can run on another with minimal changes, fostering a more open quantum cloud ecosystem.

Addressing QaaS Challenges

We discussed current challenges – limited qubits, errors, queue times, cost, etc. In the coming years, providers will work to mitigate these:

Resource availability and scaling

With more devices coming online (and existing devices scaling up), cloud queues should improve. Providers might add more parallel quantum processors (for example, IBM keeps adding machines in their fleet; AWS brings new partners).

Also, technologies like dynamic multiplexing could allow a single quantum processor to handle multiple small jobs in one execution cycle, improving throughput. We might see QaaS SLAs where providers guarantee a job will start within X minutes of submission by allocating enough capacity.

Error Mitigation and Reliability

Even before full error correction arrives, QaaS providers are layering error mitigation software so that results are more reliable. IBM, for instance, is introducing error suppression and mitigation techniques in their cloud software stack. Over the next years, cloud users might see options to toggle error mitigation on (trading a bit more shots or compute time for cleaner results).

Eventually, when true error-corrected logical qubits come (which might use thousands of physical qubits per logical qubit), QaaS will deliver a leap in reliability – at that point, one could trust the quantum cloud for mission-critical calculations because the error rates are drastically reduced. That’s the direction QaaS has to take: not just a novel toy, but the economically preferred solution for certain problems.

Achieving that requires both hardware advances (for accuracy and speed) and integration into workflows (for ease and cost-efficiency).

Pricing models

As QaaS usage grows, we might see more diversified pricing. Currently, it’s often pay-per-shot or per second. In the future, maybe subscription models for enterprises (unlimited use of a certain QPU type for a flat fee), or spot pricing (cheaper rates at off-peak times), or bundling with classical cloud services.

If quantum computers prove their worth on, say, optimization, a company might be willing to pay a premium for faster solutions – but they’ll expect reliability and support. Cloud providers will likely offer packages that include expert consulting, much like today some cloud vendors offer architectural support.