Italy’s Largest Quantum Computer Built on Open Architecture Debuts in Naples

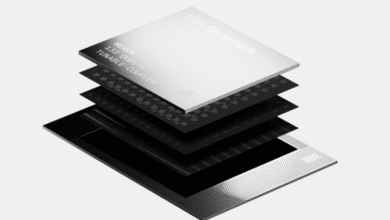

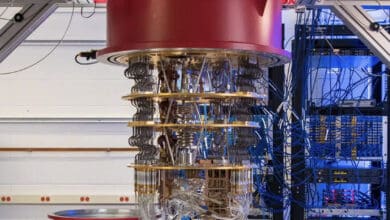

3 Oct, 2025 – The University of Naples Federico II unveiled the country’s most powerful quantum computer – a 64-qubit system assembled using a revolutionary modular design. Powered by a Tenor quantum processing unit (QPU) from Dutch startup QuantWare, this machine now stands as Italy’s largest quantum computer, marking a national milestone in quantum technology. The Tenor chip, containing 64 superconducting qubits, was delivered as a ready-to-integrate component that allowed the Naples team to rapidly build a cutting-edge system without designing their own processor from scratch. Instead of relying on a proprietary “black box” from a big vendor or undertaking a years-long in-house development, the researchers at Naples essentially snapped together a quantum computer from specialized modules – an approach that dramatically shortened the project timeline.

The new quantum system is housed at the Department of Physics “Ettore Pancini” in Naples and led by Professor Francesco Tafuri, head of the Quantum Computing Napoli (QCN) Laboratory. Tafuri explained that choosing a commercially available 64-qubit processor was crucial: “Building Italy’s largest quantum computer required a processor that was not only powerful, but commercially available and ready for integration. QuantWare’s Tenor QPU significantly accelerated our timeline and allowed us to focus on building the system and its applications.” In other words, by purchasing a ready-made quantum chip, his team could devote their effort to integrating the system and developing experiments, rather than reinventing the quantum wheel in chip fabrication. The result is a functional large-scale quantum computer built in a fraction of the time and cost it would have taken via traditional routes. Notably, the Tenor-based machine (reportedly nicknamed “Partenope”) builds upon an earlier 25-qubit prototype that the university had debuted in 2024 with national funding. By swapping in the higher-capacity Tenor processor, the Naples lab leapfrogged its initial goal of 40 qubits and firmly set a new domestic record.

This achievement highlights a broader shift in how quantum computing projects are executed. The Naples system was assembled under a Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) model, meaning the team combined multiple third-party components – the QPU from QuantWare, a cryogenic refrigeration unit, control electronics, and software – into a home-grown setup. Such plug-and-play assembly of a quantum computer was practically unheard of just a few years ago. “Before QOA players like QuantWare entered the market, any organization seeking a quantum computer had to either buy a closed system from a full-stack provider or build one from scratch,” QuantWare noted in its announcement. In contrast, the open architecture approach adopted in Naples shows that even a university lab can stand up a world-class quantum machine by sourcing parts from different specialists rather than depending on a single vendor. As QuantWare’s CEO Mattijs Rijlaarsdam put it, “Through the Quantum Open Architecture, we empower the whole ecosystem to innovate and build upon our processors. This milestone shows the effectiveness of that approach: the University of Naples is now operating a quantum computer that is beyond most of the systems built by closed architecture players.” In short, Italy’s largest quantum computer was not bought off the shelf as a sealed IBM or Google system – it was built in Naples using an ensemble of modules, showcasing Italy’s growing autonomy in this strategic technology.

Building Quantum Computers Like LEGO: The Open Architecture Model

The Naples project exemplifies the emerging paradigm of Quantum Open Architecture (QOA), often likened to building a PC from parts rather than buying a locked-down mainframe. In the traditional model, quantum computers have been vertically integrated endeavors – one company (or research lab) designs everything from the qubits and control chips to the cryogenic setup and software. This all-in-one approach, while initially necessary, kept quantum computing in the hands of only large corporations and government labs. QOA is now flipping that script. Under an open architecture, different providers supply modular components of the quantum stack, which system integrators can mix-and-match into a complete machine. For example, an institution can source a high-quality processor from one vendor, microwave control electronics from another, ultra-cold dilution refrigerators from a third, and dedicated calibration software from yet another – much like assembling a custom classical computer by choosing a CPU, a motherboard, a GPU, etc. from various manufacturers. The interoperability of these components is key: as long as they adhere to certain interface standards (frequencies, protocols, physical connectors), they can be integrated with relative ease in the lab.

This LEGO-block approach to quantum computing significantly lowers barriers to entry. Instead of sinking massive R&D into every layer of the technology, universities and startups can leverage the expertise of specialized companies for each piece of the puzzle. In Naples, for instance, the team paired QuantWare’s 64-qubit chip with control hardware and cryogenics that were locally sourced or already available, allowing them to concentrate on system integration and application development. The open architecture ethos mirrors the evolution of classical computing: in the PC era, a rich ecosystem of suppliers (Intel for CPUs, Seagate for disks, etc.) meant organizations could assemble their own computers by buying components, rather than relying on a single mainframe provider. Quantum computing is now heading down a similar path. By specializing in QPUs and selling them widely, companies like QuantWare aim to turbocharge scaling across the industry – their processors can end up in many projects worldwide, each project sparing the cost and time of developing a quantum chip in-house.

Crucially, the QOA model doesn’t just replicate what full-stack giants offer – it offers flexibility. Researchers can tailor a system to their needs: if a new control system offers better performance, they can swap it in; if a different vendor’s qubit technology improves, they might integrate that down the line. The modular Naples setup, for example, gave the local team deep insight into each component, from fridge to firmware, which is invaluable for debugging and optimizing experiments. This is a stark contrast to cloud-based or closed systems where users are abstracted away from the hardware. Educationally, having a hands-on, open quantum machine is a boon: students and engineers can learn how a quantum computer really works at every level, cultivating expertise that goes beyond running black-box circuits. Professor Tafuri’s students will thus gain experience in everything from qubit calibration to cryogenic maintenance – skills that are in short supply and high demand as the quantum sector grows. The open architecture also fosters collaboration: labs with similar modular setups can share techniques and even components, because they speak the same “hardware language.” We’re already seeing multi-vendor quantum collaborations emerge – for instance, a late-2025 project in Colorado combined QuantWare qubits, Qblox control electronics, Q‑CTRL software, and Maybell refrigerators into a unified testbed, demonstrating a multi-partner Lego approach to quantum computing. All these trends indicate that QOA isn’t a one-off experiment in Naples, but part of a growing movement to democratize access to quantum computing technology.

Quantum Sovereignty and the European Perspective

Beyond the technical triumph, Italy’s new quantum computer carries strategic significance for Europe. Policymakers have increasingly emphasized the need for quantum sovereignty – the idea that nations (and the EU as a whole) should control their own quantum technology destiny, rather than depend entirely on foreign giants. The European Union has explicitly set a goal of achieving “full-stack quantum sovereignty,” meaning the capability to produce everything from the quantum chips up through the software within Europe’s borders. The Naples project is a tangible step in that direction. By sourcing a QPU from a European company (the Netherlands’ QuantWare) and building the system locally, Italy now has a home-grown quantum computer under its roof. It’s a far cry from leaning on IBM in New York or Google in California for quantum access – instead, Italian researchers can physically access and modify their machine on site, gaining independence and expertise. This aligns with a broader movement in Europe: we’ve seen countries like Germany, France, Finland, and Spain invest in domestic quantum hardware initiatives, whether through startups or partnerships, to ensure they aren’t left behind in the quantum race. The EU’s quantum flagship programs and national plans (such as Italy’s PNRR funding that helped launch Naples’ first 25-qubit Partenope system) all underscore this drive for sovereignty in critical tech.

Italy in particular is quickly ramping up its quantum capabilities. In addition to the Naples open-architecture machine, the country’s main supercomputing center CINECA is set to host an IQM “Radiance” quantum computer featuring a 54-qubit processor by the end of 2025. That system – provided by Finland’s IQM – will be integrated with the Leonardo supercomputer, illustrating Italy’s two-pronged approach: acquiring turnkey systems from European vendors like IQM while also building modular systems domestically. The University of Naples 64-qubit machine now slightly outstrips the CINECA system in raw qubit count, seizing the national title for largest quantum computer (and placing Italy among the few countries with a 50+ qubit device operational on their soil). These efforts serve a greater purpose than just bragging rights. They cultivate local high-tech ecosystems: each machine requires skilled technicians, quantum engineers, and algorithm developers, thereby creating jobs and know-how in Italy. Moreover, having indigenous quantum infrastructure means Italian and EU researchers can pursue sensitive research (for example, in quantum cryptography or defense applications) without relying on foreign cloud platforms – a key aspect of technological sovereignty.

The QuantWare QPU delivery itself was part of a wider strategy to build out a European supply chain. QuantWare’s upcoming KiloFab in the Netherlands (scheduled to open in 2026) will be Europe’s first dedicated quantum chip factory, aimed at mass-producing advanced superconducting processors on the continent. Initiatives like that dovetail with Europe’s desire to control fabrication and not be beholden to US or Asian foundries for critical quantum components. Quantum sovereignty, in practice, means Europe can design, build, and operate quantum computers end-to-end: from the qubit devices (e.g. made in a Dutch fab), to cryostats (often made by Finnish or German firms), to control electronics (with players like Zurich Instruments in Switzerland or Quantum Machines in Israel/Europe), all the way up to software (with companies like France’s Pasqal or Finland’s Algorithmiq contributing algorithms and middleware). By assembling these pieces, European consortia can create cutting-edge systems that rival those of the US tech giants – and do so on European terms. The Naples milestone vividly illustrates this potential: a Dutch chip + Italian lab integration + pan-European know-how equals a state-of-the-art quantum computer in Italy. As Mattijs Rijlaarsdam observed, such open architecture projects give smaller countries and new entrants a chance to build quantum machines “for perhaps single-digit millions of dollars, rather than embarking on a decade-long, open-ended research project”. In other words, QOA provides a fast track for nations to achieve quantum capability now, accelerating Europe’s collective progress.

Conclusion

Standing back, the success in Naples feels like more than just one lab’s achievement – it’s a proof-of-concept for a new way of advancing quantum computing. As someone who has followed the field’s twists and turns, I find this development particularly exciting because it lowers the barrier to participation in quantum research. When world-class quantum hardware can be obtained as a product (not unlike buying a high-end server or GPU accelerator), it means universities and companies outside the traditional elite can start experimenting with real quantum processors on-premise. This democratization will likely spark innovation in places we wouldn’t expect. We might soon see quantum computers popping up at smaller European universities or startups in emerging tech hubs, all thanks to the availability of modular components and open standards. History suggests that open ecosystems (think of the PC industry or the internet) tend to drive faster adoption and community-driven improvements than closed, proprietary ones. The coming years could therefore see a dual-track evolution: on one side, the big players like IBM continue pushing their fully integrated, cloud-based machines, while on the other side an open-architecture ecosystem grows in parallel – perhaps akin to the old Mac vs PC dichotomy. Both approaches will contribute, but the open model may well accelerate the spread of quantum technology into more hands.

It’s also worth noting the element of national pride and capacity-building here. There was palpable excitement in Italy around this project (the machine was affectionately named Partenope, after a legendary figure tied to Naples). Such local milestones inspire the next generation of researchers and signal that “we too have a stake in the quantum future.” In my view, that sense of ownership is incredibly important. Quantum computing is poised to be a transformative technology, and it shouldn’t be monopolized by a few big corporations or countries. The Naples quantum computer demonstrates that with collaboration and openness, even modestly sized labs can join the frontlines of this revolution. As quantum technology marches forward, I expect the open architecture approach will prove essential for scaling up from dozens to hundreds and eventually thousands of qubits. No single company has a monopoly on all the good ideas; the more we share components and knowledge, the faster we solve the hard problems (from qubit noise to error correction).

In summary, the University of Naples’ 64-qubit quantum computer is a milestone not just for Italy but for the global quantum community. It validates a new, more inclusive model of innovation. Italy’s largest quantum computer was not imported; it was built – piece by piece – through a collaborative ecosystem. That’s a powerful narrative. The road to quantum advantage will be long, but thanks to breakthroughs like this, many more travelers can now step onto it.

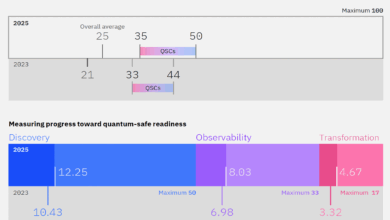

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.