Why Companies May Need a Chief Quantum Officer (CQO)

Table of Contents

Introduction

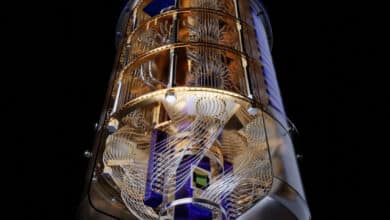

In 1882, Thomas Edison flipped a switch at New York’s Pearl Street Station, illuminating the first electric lights and astonishing the world. In the early days of electrification, businesses were so perplexed by this new technology that many appointed “Chief Electricity Officers” to manage and integrate electrical power into their operations. Of course, as electricity became ubiquitous, those roles vanished into history’s footnotes. Today, we stand at a similar crossroads with quantum technology. Quantum computing and related quantum innovations promise to reshape industries as profoundly as electricity once did – and it begs the question: who should be in charge of “flipping the quantum switch” for a company?

In my opinion, forward-thinking organizations should consider creating a Chief Quantum Officer (CQO) role. Much like those historical electricity executives, a CQO would spearhead the adoption of a disruptive technology that is revolutionary, promising – but widely misunderstood. It’s a provocative idea (even “a job title from Star Trek,” as one commentator quipped ), but it’s quickly moving from speculation to reality. A few bold companies have already appointed CQOs, signaling that quantum tech is becoming a strategic priority, not just a research experiment. I’m personally bullish on quantum’s potential, and while I expect quantum computing to become commoditized in the coming decades (eventually making a CQO as obsolete as the Chief Electricity Officer), I believe that for the next several years a dedicated quantum leader could be invaluable. Here’s why.

Chief Electricity Officers and Quantum Parallels

At the turn of the 20th century, electricity was the cutting-edge technology that promised huge competitive advantages – if you could figure out how to harness it. It was complex and unfamiliar. Companies like factories and railroads literally hired “chief electricity officers” to oversee the transition from steam power to electric motors and to manage in-house power plants. This wasn’t a vanity position; it was essential at the time. Eventually, as electric grids became standard and every engineer understood electricity basics, the specialized role faded away. No modern company has a Chief Electricity Officer – electrical know-how became a common utility, woven into every facet of business.

Quantum computing today bears resemblance to electricity in those early days. It’s radically powerful and full of promise, yet also arcane and nascent. The theory of quantum mechanics defies our everyday intuition, and building useful quantum computers remains a formidable scientific challenge. In other words, quantum tech in 2025 is where electricity was around 1900 – on the cusp of changing everything, but not yet an everyday tool. Just as electricity eventually went from experimental to ubiquitous, many of us expect quantum technology to follow a similar trajectory. And that suggests a pattern: early on, we may need specialized leadership to integrate quantum into business strategy; later, once quantum capabilities are as common as electricity or internet access, the dedicated CQO role might no longer be necessary. That eventual obsolescence of the role would actually signal success – quantum tech would have become “business as usual.”

The Emergence of the Chief Quantum Officer

The idea of a Chief Quantum Officer is no longer hypothetical. A small but growing number of organizations have created dedicated quantum leadership positions in recent years, effectively saying “quantum is strategic to us.” For example, QuantumBasel – a Switzerland-based quantum innovation hub – appointed Dr. Frederik Flöther as its CQO, explicitly charging him with driving quantum solutions and partnerships for the enterprise. Another example is BTQ Technologies, a quantum security firm, which promoted a leading quantum researcher to Chief Quantum Officer to steer the company’s technological roadmap.

Even outside the private sector, we see the CQO concept taking hold. The U.S. state of Illinois recently appointed Dr. Preeti Chalsani as a Chief Quantum Officer to coordinate quantum technology initiatives and attract quantum tech companies to the state. “Chief quantum officer might sound like a job title from Star Trek, but Dr. Chalsani works right here in Chicagoland – not on the deck of the Enterprise,” noted one news article, highlighting how quickly a sci-fi-sounding role has become a real-world need. Her mandate as a public-sector CQO is to focus full-time on quantum industry development – essentially acting as a “quantum czar” for the region.

These early appointments send a clear message: quantum technology is moving from the lab to the boardroom. Organizations appointing a CQO are telling their stakeholders (investors, customers, partners) that we take quantum seriously. It’s no longer purely academic or theoretical; it’s part of our strategic planning now, not at some distant future date. Importantly, a CQO role also signals internally that quantum isn’t just an R&D experiment siloed in the IT department – it’s something the company will integrate across functions, with leadership attention at the highest level.

Why Create a CQO Now? Opportunity and Threat

Skeptics might argue that it’s premature to add a Quantum Officer to the executive team when practical quantum computing is still developing. It’s true that today’s quantum computers are modest in scale, measured in qubits that often number in the hundreds at most, and many experts estimate we are years away from large, error-corrected quantum machines capable of solving broad commercial problems. So why not wait? The short answer: the stakes are simply too high, both in opportunity and in risk, to ignore quantum developments until later.

On the opportunity side, quantum computing has the potential to be as transformational as the advent of the internet or the smartphone. These machines exploit strange physics to process information in ways that classical computers fundamentally cannot. The result is the chance to solve certain classes of problems exponentially faster or more efficiently. This isn’t just academic speculation – it’s already being demonstrated in laboratories. Companies like IBM, IonQ, and Google have aggressive roadmaps aiming to scale quantum processors into the thousands of qubits within this decade. For example, IonQ anticipates that by around 2028 their systems will outperform classical supercomputers on useful problems. If even some of these predictions materialize, organizations that have prepared for quantum could leap ahead of competitors in areas like optimization, AI, materials discovery, and beyond. As one survey of business leaders found, 63% believe commercialized quantum computing will hit the market within five years, and 90% believe their company’s operations will be transformed by quantum by 2030. In other words, many CEOs and CTOs suspect the quantum future might arrive faster than it appears.

Equally important is the threat side of the equation – particularly in cybersecurity. Quantum computers pose an existential challenge to today’s encryption and security infrastructure. A powerful enough quantum computer could potentially crack the RSA and ECC encryption algorithms that secure virtually all digital communications, financial transactions, and confidential data. This isn’t a far-off theory; it’s a looming reality that security experts have dubbed “Q-Day” – the day when quantum code-breaking becomes possible. Some analysts predict that state adversaries might have quantum decryption capabilities by as early as 2028. Moreover, attackers aren’t waiting for Q-Day; they are stealing encrypted data now and storing it, anticipating that they’ll decrypt it later when they have quantum tools – a strategy ominously known as “harvest now, decrypt later”. This puts a ticking clock on organizations to start upgrading their cryptography (often referred to as post-quantum cryptography, or PQC). The effort required to transition all of an enterprise’s systems to quantum-safe encryption is massive and could take many years, so waiting until the last minute is a recipe for disaster. A Chief Quantum Officer can champion and coordinate this urgent transition to quantum-safe security, working hand-in-hand with CISOs to ensure the company’s sensitive data isn’t the low-hanging fruit when quantum attacks become feasible.

In summary, we have a classic case of “high risk, high reward.” Quantum tech carries extraordinary promise – new products, new efficiencies, perhaps whole new business models – but also significant peril if not managed proactively. A CQO is essentially a response to both: a proactive move to seize the upside (making sure the company is quantum-ready to exploit advantages) and to guard against the downside (mitigating quantum threats before they strike). History has taught us that technological revolutions reward the prepared and punish the complacent. The companies that embraced the internet early, or invested in AI early, reaped outsized benefits; those that dismissed those trends often had to play catch-up later. Quantum likely falls in the same category. Having a CQO now is about positioning the organization on the right side of that disruption curve.

What Would a Chief Quantum Officer Do?

The CQO’s role can be thought of as a blend of futurist, strategist, technologist, and educator. Drawing parallels to other C-suite roles, you might say the CQO is part CTO (technology strategy), part CISO (risk management), part Chief Innovation Officer (driving new initiatives), and part evangelist. In practice, here are some of the key responsibilities a Chief Quantum Officer would typically handle:

Developing a Quantum Strategy and Roadmap

The first duty of a CQO is to translate the rapidly evolving quantum landscape into a clear strategy for the business. This involves continuous horizon scanning, keeping tabs on breakthroughs in quantum hardware, software, and algorithms, and identifying when and where those advances could impact the company’s objectives. For example, if a new quantum optimization algorithm emerges that could improve supply chain efficiency, the CQO should be the one to spot it and evaluate its relevance.

They would create a quantum roadmap that aligns with the company’s overall strategy: which pilot projects to pursue first, when to ramp up investment, and which milestones to hit. In essence, the CQO answers: how will we integrate quantum tech into our products or operations, and on what timeline? This strategic planning also means setting R&D budgets for quantum initiatives and defining success metrics (e.g. achieving a certain performance improvement via a quantum solution by 2025).

Crucially, the CQO must communicate this vision to other executives and the board in plain business terms (cutting through the hype), ensuring buy-in and understanding across the leadership team.

Driving R&D and Partnerships

Because quantum computing is still maturing, no company can do it all alone. A CQO leads the research and development efforts around quantum, often by forging partnerships with the external quantum ecosystem. This might mean collaborating with quantum startups, tech giants, universities, and government labs. For instance, a pharmaceutical company’s CQO might partner with a quantum computing firm to explore drug discovery methods, or join a consortium program at a national lab. (In fact, pharma giant Roche has a quantum taskforce and teamed up with Cambridge Quantum Computing to design algorithms for Alzheimer’s research.) A CQO will decide whether to build in-house expertise or leverage cloud-based quantum services from providers like IBM and Amazon. Many companies opt for pilot projects on existing quantum platforms – a CQO ensures these projects deliver useful learnings. They also evaluate strategic investments: some corporations may even invest in quantum hardware companies or encryption tech startups to gain early access to breakthroughs.

Essentially, the CQO is the chief ambassador to the quantum industry, making sure their organization has a seat at the table for major developments. Internally, they’ll coordinate any dedicated quantum R&D teams. For example, banks like JPMorgan and Wells Fargo have built internal quantum research groups to prototype trading and risk models on quantum devices. A CQO would oversee such teams, prioritize their project portfolio, and integrate their work with business units.

Building Quantum Talent and Skills

One of the biggest challenges is finding people who understand quantum tech and can apply it to real problems. Quantum talent is scarce – the field demands PhD-level physics or math expertise, which is not common in a typical IT department. A CQO is responsible for building up the organization’s quantum-ready workforce. This includes hiring specialists (quantum scientists, quantum algorithm developers, etc.) where needed, but also upskilling existing employees. Similar to how companies in the 2010s invested in “data literacy” across the workforce, companies in the 2020s will need quantum literacy programs.

The CQO might implement training workshops or sponsor employees to take quantum computing courses (many are available via IBM’s Qiskit, Coursera, etc.). They may also rotate a few software engineers through quantum projects to seed knowledge more broadly. Part of this role is organizational change management – making sure that when quantum solutions become viable, the company isn’t limited by a talent bottleneck. Notably, a recent industry survey found 58% of business leaders feel the lack of in-house quantum skills is already a barrier to adoption. The CQO’s job is to close that gap by championing recruitment and education. They might also work on outreach to universities or sponsor research to create a pipeline of future hires.

In short, the CQO acts as the chief talent scout for quantum expertise and the mentor for growing that expertise internally.

Overseeing Quantum Risk Management and Security

As discussed, cybersecurity is the most urgent quantum-driven risk many organizations face. A CQO would work very closely with the Chief Information Security Officer to ensure the company is quantum-safe. This means leading the transition to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) – identifying where the company uses vulnerable encryption (for example, in VPNs, product firmware, customer databases, etc.) and systematically migrating those to NIST-approved quantum-resistant algorithms. Given NIST’s 2030/2035 deadlines, a CQO will create a multi-year upgrade plan, often starting with the most sensitive or long-lived data (since anything stolen today could be decrypted later). They will also keep informed on the latest in quantum threats; if there are rumors that a nation-state is near a decryption breakthrough, the CQO should be the first to know and alert the CISO.

Beyond encryption, quantum risk management also covers things like assessing supplier readiness (are our vendors using quantum-safe methods?), compliance with upcoming regulations (we may soon see requirements for certain industries to prove quantum resiliency), and even considering disruption scenarios (e.g. what if a competitor uses quantum to optimize pricing and undercuts us?)

A CQO needs to develop contingency plans for the negative side of quantum’s impact. For example, if the company’s business model relies on cryptography (say, a VPN provider or a fintech firm), the CQO must guide a pivot to new security tech in time. In essence, the CQO and CISO together ensure that quantum doesn’t become the company’s Achilles’ heel.

Cross-Functional Leadership and Education

A successful CQO can’t work in a vacuum – their role is inherently cross-functional. Quantum technologies, by their nature, can affect multiple domains at once: computing, data, security, operations, etc. The CQO must act as a translator and evangelist across the organization. They will regularly brief other executives and department heads about quantum developments, demystifying the science into plain language and concrete implications. For instance, they might present to the finance department on how quantum optimization could save costs in treasury management, or talk to the marketing team about the timeline for quantum-safe encryption in customer-facing apps.

They will also manage expectations – tamping down hype where needed. Internally, the CQO might set up a “quantum steering committee” with stakeholders from various units, to ensure a coordinated approach. A big part of the job is cultural: making sure the organization doesn’t fear quantum or dismiss it, but rather builds curiosity and openness to it.

Some companies have even started enterprise-wide quantum awareness campaigns, highlighting both the risks and opportunities of quantum to all staff. The CQO typically leads such initiatives. They might circulate periodic newsletters explaining quantum news in business terms or host lunch-and-learns. By doing so, they embed quantum readiness into the company’s DNA. When all departments are quantum-aware, the company is far less likely to be caught off guard, and more likely to spot creative uses for the tech.

In short, the CQO is chief storyteller and educator for all things quantum, ensuring the organization as a whole steps into the quantum era confidently and cohesively.

These responsibilities illustrate why a CQO is often a hybrid talent. The person needs a deep grasp of quantum tech (to know what’s feasible and when) but also business acumen and communication skills to drive strategy and change. Such people are rare, which is one reason not every company has a CQO yet – but more on that challenge later. The key point is that a CQO provides focused leadership on a domain that would otherwise be too easy to neglect amid day-to-day pressures. If no one is clearly in charge of quantum strategy, it’s likely to fall between the cracks or suffer from disjointed efforts. The CQO fills that leadership vacuum.

Industries Primed for Early Quantum Adoption

Quantum computing is a general-purpose technology, so eventually it will touch almost every sector – similar to how the internet became universal. But in these early days, some industries are positioned to benefit from (or be disrupted by) quantum much sooner than others. These are the sectors where having a CQO today could yield the greatest immediate gains or protective value. Based on current developments, a few standout industries include:

Finance and Banking

Financial services are at the forefront of quantum exploration. Big banks handle extremely complex computational problems (portfolio optimization, risk modeling, trading strategies) and also heavily rely on cryptography – making them hungry for quantum’s upside and anxious about its downside. It’s no surprise many banks have dedicated quantum research teams and initiatives. JPMorgan Chase, for example, was one of the first to invest in an internal quantum team and has been actively publishing quantum algorithms for finance. Goldman Sachs and HSBC are similarly known as quantum front-runners. HSBC notably has been piloting quantum-safe encryption and quantum networks in anticipation of security threats – in 2023 they became the first bank to join a quantum-secured fiber network in the UK, testing quantum key distribution for financial data. HSBC’s leadership explicitly stated they are “already preparing [our] global operations for a quantum future… spearheading trials, recruiting experts, and investing in partnerships” to not fall behind. That kind of top-down drive is essentially what a CQO would champion. In fact, a recent industry report ranked JPMorgan, HSBC, and Goldman as top quantum innovators in finance.

The quantum threat to encryption is also a huge motivator for banks to act now – regulators and central banks are nudging financial institutions to begin upgrading crypto systems. A CQO in a bank would likely prioritize this transition to post-quantum cryptography (so that customer data and transactions remain secure) while also pushing quantum computing pilots in areas like fraud detection, asset pricing, and trading optimization. Given that banking executives deal with probabilities and risk daily, many are keenly aware that a small lead in quantum capabilities could compound into a big competitive edge. It’s telling that over 45% of major banks already have a dedicated quantum computing group or partnership supporting their efforts.

Pharmaceuticals and Healthcare

The pharma industry might gain some of the earliest practical benefits from quantum computing. Drug discovery and materials chemistry are classic examples of problems that quantum computers can accelerate – because they involve simulating quantum-mechanical interactions (e.g. how a drug molecule binds to a protein) that overwhelm classical computing. Today, discovering a new drug is a decade-long, billions-of-dollars endeavor with lots of trial and error. Quantum simulations promise to cut that time and cost dramatically by searching chemical compound space more efficiently. Pharma heavyweights are paying attention: Pfizer, Merck, Roche, and others have all launched quantum research collaborations. We mentioned Roche’s partnership with Cambridge Quantum on Alzheimer’s research; another example is Pfizer’s work with IBM Quantum on molecular simulation algorithms.

According to one analysis, 65% of large pharma companies have already initiated quantum computing pilot programs in their R&D departments. Moreover, industry surveys show roughly 70% of pharma executives believe quantum computing will be mainstream in drug discovery within the next decade – a remarkably optimistic outlook driven by early results.

A Chief Quantum Officer in a pharma firm would coordinate these R&D efforts, ensure the company is investing in the right partnerships (perhaps connecting with startups in quantum chemistry software), and manage intellectual property that comes from quantum-developed drug candidates. They’d also need to handle the talent aspect, since quantum chemistry experts and quantum machine learning specialists are in high demand. Beyond drug discovery, quantum sensors might improve medical imaging or diagnostics, and quantum machine learning could help with personalized medicine – areas a healthcare CQO would monitor.

In summary, pharma sees quantum computing as a critical accelerator for innovation, and we can already observe companies treating it as such. (On a related note, QuantumBasel’s CQO that we discussed is actually working closely with pharma companies and startups to build quantum-enhanced tools for physicians, showing the cross-pollination between quantum tech hubs and the healthcare sector.)

Logistics, Manufacturing & Supply Chain

These industries involve complex optimization problems – exactly the kind of tasks certain quantum algorithms excel at. Routing delivery trucks, scheduling factory lines, managing supply chain inventories across the globe – all involve juggling thousands of variables to find cost and time efficiencies. Quantum computers (even today’s early models, like quantum annealers) have shown promise in solving optimization problems faster or better than classical methods for certain cases. For example, DHL and FedEx have experimented with quantum algorithms to optimize delivery routes and fleet schedules, aiming to reduce fuel consumption and shipping times. In manufacturing, companies have tested using quantum computers to optimize the design of factory floor layouts and the calibration of robotics. Airbus and Boeing have looked into quantum computing for more efficient airplane routing and cargo loading solutions.

A CQO in a logistics or manufacturing firm would spearhead these proof-of-concept projects and then work to integrate successful quantum solutions into daily operations. The ROI in this sector can be immediately tangible – even a few percentage points improvement in supply efficiency or resource usage can save millions of dollars for a large operation. Additionally, manufacturers and retailers learned during recent global supply chain disruptions that smarter, more flexible optimization is key to resilience. Quantum computing could become a differentiator here.

It’s notable that when IonQ announced a major deployment of its quantum systems in Europe, it specifically highlighted expected applications in logistics and chemistry among others. That suggests the quantum industry itself sees logistics as a prime early market. So, a CQO for a company in these fields would not only chase operational benefits but could also market the company’s quantum-driven efficiency to customers as a competitive advantage (for instance, “your package arrives faster because we use cutting-edge quantum optimization”).

Energy and Materials

Energy companies (oil & gas, utilities, renewable energy firms) and materials science companies stand to gain enormously from quantum computing’s simulation power. Quantum chemistry can lead to discovering new catalysts, better battery materials, more efficient solar cells, and improved chemical processes – all vital for the energy sector. For example, finding a catalyst that makes hydrogen production cheap could revolutionize clean energy, and quantum computers are ideal for exploring such chemical reaction pathways. In materials science, quantum simulations might help design high-temperature superconductors or lighter alloys for aerospace. Big players like ExxonMobil and Total have dabbled in quantum computing research for optimizing energy distribution and modeling subsurface geology for oil exploration. Additionally, the energy grid optimization (balancing loads, integrating unpredictable renewable sources, etc.) is a huge mathematical challenge that quantum algorithms could help tackle.

A CQO in an energy company would coordinate with R&D teams on these applications, likely partnering with hardware vendors and national labs that have the expertise. They’d also watch the quantum sensor space: quantum-enhanced sensors can, for example, detect underground resources or monitor grid equipment with unprecedented sensitivity. Governments around the world are investing heavily in quantum tech with an eye on energy and climate solutions. In fact, over 30 countries have committed more than $35 billion in quantum R&D funding collectively, much of it in areas overlapping with energy, chemistry, and materials. So, a CQO in this sector also works on leveraging public grants and shaping research consortia so their company stays at the cutting edge. There’s a national competitiveness angle here too – energy companies don’t want to fall behind foreign rivals in advanced tech. Notably, BP and Airbus joined IBM’s Quantum Network to collaborate on relevant use cases (BP for energy, Airbus for materials and optimization).

Defense, Security & Government

While traditional corporations may style the role differently, the defense and national security realm effectively has equivalents of CQOs emerging. Military organizations, intelligence agencies, and defense contractors are extremely attuned to quantum technology. The reasons are clear: quantum capabilities could provide strategic military advantages (e.g. code-breaking, new sensors for submarine detection, optimized logistics for troop deployment) and at the same time, quantum threats could undermine national security infrastructure (e.g. encrypted communications, satellite security). Thus, defense entities are investing in quantum to win the race rather than lose it. The U.S., China, and European countries are pouring billions into quantum research programs. For example, the U.S. Department of Defense through DARPA has multiple quantum initiatives, and each branch of the military has officers overseeing quantum technology projects. NATO has even created a Quantum Technology project to coordinate allied efforts. Some governments have appointed what media call “quantum czars” – individuals tasked with orchestrating national quantum strategy (Dr. Chalsani’s role in Illinois is one instance at the state level).

In the corporate side of defense contracting, companies like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and L3Harris have quantum research divisions; L3Harris, for instance, hired a Head of Quantum Technology to guide its work in quantum sensing and communications.

A Chief Quantum Officer in a defense contractor or security-focused organization would manage classified quantum R&D, ensure the company’s products (like encryption devices) evolve to be quantum-safe, and interface with government partners on quantum standards and procurement. Because defense projects often have long lead times, having quantum expertise in-house early is seen as crucial. We can foresee that in sectors like telecommunications (critical infrastructure) and cybersecurity firms, similar roles will appear to address both the market opportunity of offering quantum-resistant solutions and the necessity of protecting their own networks. In short, for anyone in the business of security, quantum is an inevitable topic, and leadership is needed to navigate it.

These are some key examples, but the list could go on. Automotive companies are looking at quantum for new materials and traffic flow optimization (imagine smarter cities with quantum-optimized traffic lights). Finance-adjacent sectors like insurance are eyeing quantum for risk modeling. Academia and tech firms of course have “directors of quantum research” (if not CQOs) to push the field forward. The overarching point is: the more an industry relies on heavy computing and data or has high-value encryption at stake, the sooner quantum computing will matter to it. Those industries are naturally the early adopters where a CQO role is easiest to justify. It’s no coincidence that surveys find cybersecurity, finance, and healthcare as among the sectors expecting the fastest ROI from quantum tech. If your competitors or collaborators are diving in, having a CQO could be the move that ensures you’re not left behind in the quantum race.

Challenges and Skepticism: Why Isn’t Every Company Doing This?

Despite the strong case we can make for CQOs, it’s worth acknowledging that this is a new and unusual role – and not everyone is convinced yet. There are several practical and organizational challenges that companies face when considering a Chief Quantum Officer. These hurdles explain why, for the moment, CQOs are still relatively rare (mostly found in tech companies, startups, and early-adopter enterprises). Let’s examine a few of these challenges:

“Hype vs. Reality” Fatigue

Quantum computing has been hyped in the media for years, often with breathless headlines that a breakthrough is “just around the corner.” In truth, progress has been steady but incremental. Some executives have become jaded, thinking quantum is always a decade away and not worth concrete action today. They read about the impressive lab experiments but then see no immediate impact on quarterly results. This skepticism can make it hard to justify a new C-suite role. A CEO might ask, “Is a CQO just going to sit around researching while our core business needs attention?” The onus is on the CQO (or the proponent of creating the role) to clearly articulate the business value – to present quantum in the language of ROI and risk mitigation, not sci-fi.

Overcoming the hype fatigue requires citing tangible indicators (like competitors’ moves, or the encryption deadlines we discussed, or pilot achievements). As one quantum tech CEO advised, the key to winning over the unconvinced is to “outline ways [quantum] can lead to performance enhancements” and solve concrete problems in the business. In other words, frame it as this is not hype, this is preparation for a known disruption. Still, managing expectations is crucial – a new CQO must avoid overpromising. Ironically, if they do their job too well in tempering hype, they might make their role seem less urgent! It’s a delicate balance of inspiring action without unrealistic claims.

Defining the Role and Avoiding Turf Wars

In many organizations, technology leadership is already crowded. There’s a CIO (Chief Information Officer) handling IT, a CTO (Chief Technology Officer) focusing on product tech, perhaps a CDO (Chief Data Officer) for data strategy, and a CISO for security. Introducing a CQO could raise the question: how is this different from what our CTO or CIO should be doing? Some might argue that quantum falls under the CTO’s strategic technology scouting or the CIO’s R&D portfolio. If those executives are particularly territorial, they may resist handing over the quantum domain to a new peer. Therefore, if a company creates a CQO, it must clearly delineate responsibilities to avoid confusion.

One model is to have the CQO report to the CTO or CIO, acting as a specialist in that division – though that can dilute the “chief” status. Another model is the CQO as a peer who collaborates closely: perhaps the CTO owns classical tech and current IT, while the CQO is entrusted with future tech (quantum, and maybe adjacent things like quantum-inspired algorithms or emerging cryptography). To work, this requires executive buy-in that quantum is big enough to warrant its own swim lane.

In companies where quantum is still seen as a sub-topic, a better interim step might be giving an existing exec the title “VP of Quantum” or similar to test the waters. On the flip side, some CTOs/CIOs are relieved to have a specialist – one CTO at a major bank privately admitted that quantum computing was so outside his team’s expertise, he welcomed bringing in a quantum lead who “speaks physics” and can interface with vendors and scientists.

Organizationally, it may also make sense for a CQO to chair a cross-department quantum committee, ensuring everyone (IT, R&D, security, business units) stays aligned. The main point: introducing a CQO must be done with clarity on how they fit with existing leadership, otherwise it could create friction or redundancy.

Talent Scarcity and Credibility

Let’s say a company wants a CQO – can they find the right person? The ideal CQO is a unicorn-like individual with deep quantum technical knowledge and strong business leadership skills. Many of the top quantum experts today come from academia or tech startups, and they may not have executive experience in a large corporate setting. Conversely, a great business leader likely doesn’t know the difference between a qubit and a classical bit. This talent gap is real. Companies might solve it by pairing talent: perhaps hiring a PhD scientist as a technical deputy and a more business-oriented leader as the CQO (or vice versa). There have been instances of quantum scientists being fast-tracked into leadership – for example, QuantumBasel’s Dr. Flöther went from IBM’s quantum research division to a CQO role, showing it is possible for a scientist to take on broader strategy when given the mandate. But the pool of such people is small.

Additionally, if a company appoints a CQO who isn’t widely respected, they risk the role not being taken seriously. Imagine a scenario where the CQO can’t answer tough technical questions or, alternatively, can’t communicate with MBAs on the board – either would undermine the position’s authority. There’s also the risk of over-hyping or under-hyping by the CQO. A credible CQO must strike an honest tone: they should be excited about quantum but frank about its limitations, so that they build trust internally. This credibility is earned over time. The first person to hold the CQO title in any organization will likely face some raised eyebrows (“what exactly do you do?”), so they have to show quick wins or insights. Hiring the right individual – or assembling the right team around the CQO – is thus a critical challenge.

Measuring ROI and Justifying Budget

A CQO doesn’t come free. Between the executive compensation and the budgets for quantum projects, it can be a significant investment. Companies will ask: what’s the return, especially in the short term? Early quantum applications might not directly contribute to revenue; they could be exploratory or defensive (like spending on new encryption, which doesn’t make money, it just avoids future losses). In financially tight times, that’s a hard sell against immediate needs of the business. A savvy CQO will set tangible interim goals to justify the role. For example, they might target something like “identify two process improvements via quantum algorithms that save X cost” or “migrate 30% of our systems to PQC by next year” or even softer metrics like “establish partnerships with top 3 quantum cloud providers, giving us priority access.”

Additionally, some companies mitigate cost by expanding the CQO’s scope – perhaps the CQO also oversees AI or other emerging tech (one can imagine a “Chief Quantum and AI Officer” in a few cases). This way, they cover multiple innovation areas, providing more value for the position. Over time, if a CQO-led project yields a major breakthrough (say a new patented process or a big efficiency gain), that will cement the ROI case. But in the very beginning, it is admittedly an act of faith and strategic foresight. The board has to be convinced that not having a quantum leader could cost them much more down the road in missed opportunities or crises.

Keeping Up with Rapid Change

Quantum technology isn’t a static field – it’s evolving rapidly and unpredictably. This means a CQO must constantly update the strategy. A plan made in 2023 might be obsolete by 2025 because a new type of qubit emerged or because a competitor found a shortcut to quantum advantage. This “moving target” nature is a challenge in itself. There’s a risk of betting on the wrong horse: maybe a CQO invests heavily in a particular quantum platform or partnership that doesn’t pan out. If, for instance, a company aligned with one hardware vendor and a year later another vendor leapfrogs them, the CQO has to pivot quickly (and explain sunk costs). To mitigate this, good CQOs adopt a portfolio approach – they spread bets across a few key areas (e.g. try out both superconducting and photonic quantum processors, or invest in both PQC and quantum key distribution for security). They also build in flexibility, continually revisiting the roadmap. It’s a bit like steering a ship through unknown waters; you need to adjust course as new information comes in. Companies must accept that a quantum program might not follow a straight linear progress – there will be trial and error. In some cases, quantum hype cycles could impact internal support: we had a mini “quantum winter” around 2022-2023 where funding and enthusiasm dipped as people realized how hard error correction is. If another disillusionment wave comes, a CQO might find budgets cut just when a breakthrough is around the corner. They need resilience and the ability to make a strong business case to sustain through any hype fatigue.

Given these challenges, it’s understandable why many companies are in “wait and see” mode. A 2024 survey found that while 91% of business leaders are at least exploring quantum use cases, most also acknowledge a “fundamental gap” between quantum’s development and their own preparedness. In other words, they know it’s important but haven’t caught up in planning. The report concludes that “a dedicated quantum leadership position…will become essential” as this gap widens. So we may just be in an interim phase where the idea of a CQO is gradually moving from novel to normal as awareness grows and the above challenges are overcome.

Looking Ahead: Will the CQO Role Last?

Let’s fast-forward in our minds, say 20 or 30 years. Quantum computing (and quantum communication, quantum sensors, etc.) have matured and are part of everyday technology. Perhaps by then we have error-corrected quantum computers running in cloud data centers solving complex optimization and simulation tasks routinely. By that time, quantum tech will likely be taught in universities as a standard part of the computer science or engineering curriculum. In such a future, will companies still need a Chief Quantum Officer?

The honest answer is probably not – and that’s a good thing. Recall the story of the Chief Electricity Officer: once every executive understood the basics of electricity and it became just another utility, having a specialized “electricity czar” was unnecessary. We can expect a similar fate for the Chief Quantum Officer. As quantum know-how permeates the workforce and as quantum tools become as common as cloud services are today, the distinct “quantum” label might disappear from the C-suite. The responsibilities would be absorbed into the conventional roles: the CTO will naturally handle quantum computing as just “computing”, the CISO will handle quantum-safe security as just “security”, etc. In fact, a CQO’s ultimate goal could be to work themselves out of a job – by successfully embedding quantum capabilities into all relevant parts of the business. When everyone is “quantum fluent,” you no longer need a single quantum point-person.

However, it’s important to emphasize that the eventual disappearance of the role won’t mean it was a mistake. On the contrary, it will mean the CQO succeeded in helping the organization navigate the quantum revolution. The timeframe for this transition is hard to pin down; it likely depends on how fast quantum tech evolves and how quickly companies adapt. I suspect we have a couple of decades where quantum expertise will confer special competitive advantage (and thus merits a special role). Beyond that, quantum computing might become commoditized – much like classical computing is now – available through cloud APIs, integrated into standard IT solutions, abstracted so that end-users don’t need to understand the quantum physics under the hood. When that commoditization happens, having a CQO would feel as odd as having a “Chief Internet Officer” today. In fact, there were companies in the 1990s that briefly had Chief Internet/Digital Officers to spearhead adoption of web technology – many of those roles then folded back into broader IT or marketing roles once the internet was fully absorbed into business operations. I foresee the CQO role following a similar arc.

So, yes, the CQO may be a transient role. But transient roles can be critically important during transitions. The Chief Data Officer role, for example, emerged over the last 15 years to help companies become data-driven; now data is so ingrained that some argue the CDO role will fade as data strategy becomes a core competency of all execs. Yet without those CDOs, many firms would never have made the jump. Likewise, the CQO is a product of this unique moment in time – the dawn of the quantum era – and serves a purpose to ensure a successful leap into a new paradigm.

One more speculative thought: it’s possible that the CQO role could evolve rather than vanish. For instance, as quantum tech matures, the scope of the role might broaden into something like “Chief Emerging Technology Officer” or “Chief Science Officer” (in a corporate context) who oversees not just quantum but whatever next radical tech comes along (perhaps neuromorphic computing or advanced biotech, etc.). In some companies, the CQO might already be taking on a portfolio of frontier tech. This would mirror how some early Chief Mobile Officers or Chief Digital Officers eventually became broader CTOs once digital was mainstream. The title is less important than the function – which is providing leadership in uncharted tech territory.

Conclusion

Every so often, a technology comes along that forces businesses to reimagine how they operate. Quantum technology is shaping up to be one of those disruptors. We’re still in the early chapters of this story, but the plot is accelerating. Companies now face a choice: proactively engage with quantum innovation (and disruption) or react later when it’s potentially too late. Appointing a Chief Quantum Officer is, in effect, a statement that a company intends to lead rather than follow – to be the disruptor, not the disrupted.

In my view, the real question isn’t whether companies will eventually need to address quantum at the executive level; it’s how soon they recognize that they should. Those that wait until a sudden quantum breakthrough occurs (say a competitor achieves a quantum-based cost reduction, or an encryption crisis hits) will be in scramble mode, trying to catch up. By contrast, those who invest early – by hiring talent, experimenting with pilots, beefing up security, and crafting a roadmap – will be able to pivot smoothly and seize the advantages when the time comes. It’s analogous to having a disaster evacuation plan versus winging it during an actual disaster.

I’ve argued that a Chief Quantum Officer can be the linchpin of that preparedness. This isn’t about creating fancy titles for the sake of it; it’s about acknowledging that quantum tech represents both a strategic opportunity and a strategic risk significant enough to merit focused leadership. A good CQO brings clarity to a murky landscape, turning quantum from a buzzword into a concrete strategic pillar – something the entire company can rally around, whether it’s innovating new solutions or safeguarding existing assets.

Not every organization is ready for a CQO today, and that’s okay. The idea will gain traction first where it’s needed most (we’ve highlighted finance, pharma, and others). But consider this: just a few years ago, most companies didn’t have a cloud strategy or an AI strategy at the board level, and now many do. Quantum is on a similar trajectory. A survey of tech leaders found that 64% believe the CQO role will become almost as important as the CIO in the foreseeable future. Boardrooms are waking up to the fact that quantum is not science fiction – it’s a coming business reality, one that cuts across product innovation, risk management, and long-term competitiveness. As that awareness spreads, the demand for quantum leadership will only grow.