Deep-Tech Commercialization Challenges in the EU

Table of Contents

Europe’s Innovation Paradox: Strong Research, Weak Commercialization

Europe is a global powerhouse in deep-tech research – from quantum breakthroughs to biotech – yet it struggles to turn this scientific excellence into market success. In fact, Europe’s deep-tech sector holds immense potential (estimated at €8 trillion) but lags behind the US in funding and commercialization, with only a fraction of innovations translating into market-ready products. European startups produce impressive patent output and cutting-edge R&D, but too often these breakthroughs “perish in the valley of death” between lab and market deployment. The result is a persistent gap: Europe generates world-class innovations, yet comparatively few deep-tech startups scale into global commercial leaders.

Multiple studies and reports have dissected this commercialization gap. A joint European Patent Office/EIB analysis, for example, found that three-quarters of deep-tech SMEs in both the EU and US cite access to finance and lack of skilled talent as major barriers. Europe’s challenge is particularly acute in later stages of growth: despite an increase in early-stage deep-tech funding, European companies are half as likely as US startups to raise large growth rounds. This funding gap at scale-up stage is estimated at hundreds of billions of euros, often forcing European founders to seek American or Asian investors to fuel growth. In short, Europe’s deep-tech innovation engine is firing on all cylinders, but its commercialization gearbox is not fully engaging.

Key Factors Holding Back European Deep-Tech Startups

Several structural and cultural factors explain why Europe often trails in bringing deep-tech to market. Key reasons identified by research include:

Fragmented Markets & Regulations

Unlike the relatively unified U.S. market, Europe’s regulatory landscape is highly fragmented along national lines. Startups must navigate diverse rules, taxes, standards, and languages across 27 countries, adding cost and complexity to expansion. As one analysis put it, “Europe’s tech ecosystem faces significant challenges from a fragmented regulatory landscape and excessive bureaucracy, hindering startup growth and cross-border expansion.” Even within the EU single market, differences in regulations (e.g. over 100 different VAT rates, various product certification regimes) force startups into multiple compliance cycles. This slows down scaling: for instance, fintech scale-up Wise had to establish entities in a dozen countries and spent over €50 million on compliance and licensing to operate across Europe. These burdens can dramatically lengthen sales cycles and delay market entry.

Funding Gaps and Risk Aversion

European deep-tech founders face a scarcity of late-stage capital. Venture capital in Europe is improving, but growth-stage rounds remain smaller and rarer than in the US. Investors in Europe tend to be more cautious – many “look for others to make the first move”, leading to a collective action problem where no one leads the big rounds. As a result, European startups often raise less money at lower valuations, making it harder to attract top talent and investors in subsequent rounds.

A recent report noted U.S. tech companies are twice as likely as European ones to secure $15M+ rounds, contributing to an estimated $375 billion growth-stage funding shortfall in Europe over the past decade.

Furthermore, Europe’s institutional investors (like pension funds) contribute only a “rounding error” of their capital to VC – around 0.01%, far below U.S. levels. This conservative funding environment stems in part from cultural risk aversion and fewer experienced lead investors willing to bet on unproven deep-tech ventures.

Talent and Mobility Constraints

Talent acquisition is a top pain point for European startups – 62% cite it as their biggest scaling challenge. Europe produces excellent scientists and engineers, but startups struggle to hire people with both technical and business skills, especially those experienced in scaling companies. Rigid labor laws and less intra-Europe relocation also hinder scaling teams quickly across borders.

In the U.S., talent is more fluid; by contrast, in Europe each country has distinct labor regulations and language requirements, limiting skilled workers’ mobility (only ~3% of EU residents move countries annually vs ~10% interstate in the US). Northvolt, a Swedish battery venture, illustrated this by having to open engineering hubs in Sweden, Germany and Poland to access specialized talent – dealing with different hiring rules in each and adding ~15% to operating costs while slowing product cycles by months. Such hurdles often keep startups focused on their home market, capping their growth.

Cultural Attitudes and Fear of Failure

Culture shapes entrepreneurship, and Europe tends to be more risk-averse. Many European societies stigmatize business failure more strongly than the U.S., which can dampen bold decision-making. According to one survey, 54% of Europeans associate startup failure with shame, versus only 27% in the US. This mindset makes founders and investors more cautious. Fewer “all or nothing” moonshot bets are taken, and struggling ventures may hesitate to pivot aggressively for fear of failing publicly. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor found some countries like Spain and Italy have “fear of failure” rates above 60% among entrepreneurs.

This risk aversion translates into smaller bets and a preference for incremental progress, which in the fast-moving tech world can mean falling behind more daring competitors. European founders also often come from academia (PhDs, researchers) and may maintain a more conservative, scientist mindset in running startups – thorough and precise, but sometimes lacking the aggressive growth mentality seen elsewhere.

University Tech Transfer Bottlenecks

A significant share of Europe’s deep-tech originates in universities and research institutes. However, the process of spinning out companies from academia can be slow and encumbered by bureaucratic tech transfer offices (TTOs). Many European universities take large equity stakes (15-25%) in spin-offs by default, aiming to capture value from IP. This often discourages founders and external investors – a startup burdened with a quarter of its equity locked up in a university’s hands is less attractive to VCs.

Moreover, TTOs are sometimes under-resourced and overly bureaucratic. Prolonged contract negotiations, complex IP agreements, and internal approval loops can drag on, slowing time-to-market for deep-tech innovations.

As a result, promising technologies may languish while paperwork is sorted out or deals stall over legal terms. Streamlining tech transfer and adopting more founder-friendly policies (as seen in some UK and Scandinavian universities) is crucial so that EU innovation isn’t held back by its own institutions.

In summary, Europe’s deep-tech commercialization hurdles are multifaceted – spanning funding, regulation, talent, culture, and institutional practices. These factors interlock to throttle the growth of startups at exactly the stage they should be accelerating. Market fragmentation and red tape slow them down; cautious capital and fear of failure keep them small; and academic habits sometimes conflict with market realities.

The good news is that none of these are insurmountable – but overcoming them requires self-awareness and adjustments from all stakeholders.

The Work Culture Divide: Balancing European Values with Global Demands

One often overlooked factor in this conversation is work culture – specifically, whether European working habits are conducive to the breakneck pace of global tech commercialization. Many European countries prize work-life balance, reasonable hours, and employee well-being – a stance that has produced enviable quality of life and strong worker protections. However, when a small deep-tech company is trying to win customers and investors across the world, a strict 9-to-5 mentality can become a liability. European founders and teams have faced criticism for not displaying the same “hustle” as their American or Asian counterparts, sparking a debate in the tech community about the role of work habits in startup success.

Recent discussions highlight this cultural divide. In 2025, Revolut CEO Nik Storonsky openly criticized European startup entrepreneurs for “not working hard enough” and valuing work-life balance too highly to compete with U.S. or Chinese peers. Similarly, some venture capital voices urged European founders to adopt a seven-day workweek if they want to win – effectively to match Silicon Valley’s infamous 24/7 grind culture. Such comments drew sharp backlash from European tech leaders, who called these expectations “toxic” and “childish”. They argue that burnout and unsustainable hours are not a healthy foundation for innovation. As Balderton Capital’s Suranga Chandratillake put it, sprinting nonstop is bad advice – “even sprinters don’t sprint all the time; rest and reflection are just as important”.

This debate underscores a core tension: European startups want to maintain human-centric work practices but also need to satisfy customers and investors who often expect round-the-clock dedication. The reality on the ground may be more nuanced than the stereotypes. A survey of 128 European founders found 75% already work more than 60 hours a week (nearly 20% exceed 80 hours), challenging the notion that EU entrepreneurs aren’t putting in the effort. Nevertheless, perceptions persist that European teams may be less “hungry” or responsive, especially when dealing with clients in fast-paced markets like the US.

From a client’s perspective, these cultural differences can make or break deals. Americans often equate speed and responsiveness with reliability, while Europeans tend to protect meal times, weekends, and holidays to recharge. For example, a U.S. corporate customer might expect immediate replies to inquiries, meetings at odd hours to accommodate time zones, and rapid turnaround on proposals. A European deep-tech startup, by contrast, might stick to business hours, delay scheduling important meetings until after an upcoming vacation period, or be reluctant to provide 24/7 support from a small team. Indeed, many European countries even legislate these boundaries – France, for instance, famously has a 35-hour workweek norm and a “right to disconnect” after hours. In practice, this could mean a French or German tech firm is uncomfortable with late-night calls or weekend crunch work that a Silicon Valley firm would consider standard in crunch time.

Consider a hypothetical scenario that mirrors some of my own anecdotes from global tech business: A procurement team in New York is evaluating an AI solution from an EU startup versus one from an American startup. The European team proposes a meeting two weeks out (within their working hours), to discuss a pilot project, whereas the American startup’s CEO says, “I can fly out tomorrow and meet you at 8am or 8pm, whatever works.” The American team also offers an on-site engineer for support during the trial. Meanwhile, the European startup, constrained by a small staff and a culture of not overworking employees, offers support only during its local 10am-4pm window. Even if the European product is superior technologically, the client may gravitate toward the vendor that feels more responsive and committed to their needs. In global business, agility and customer service often trump a slight technical edge.

This is not to say European startups are lazy – far from it. It’s about alignment of expectations. Work-life balance is a laudable ethos, and Europe rightly champions sustainable work habits that prevent burnout. However, early-stage startups operating internationally might need to adapt their approach to meet customers where they are. That could mean hiring a business development lead or support engineers in the target market (e.g. having a U.S.-based team member who works U.S. hours), or rotating staff shifts to cover different time zones. It might also involve culturally educating the core team on the customer’s expectations – for instance, explaining that in the U.S. a client email sent on Friday evening might implicitly expect a response by Saturday, whereas in Europe it can surely wait until Monday. Bridging these gaps in responsiveness and service can be the difference between winning a crucial early contract or watching a competitor swoop in.

Importantly, European startups don’t have to abandon their values to compete – they just need to be flexible and smart. One approach is to “localize” their business practices for each market. If selling to U.S. enterprise customers, hire some Americans who understand the fast-paced corporate culture and can provide on-call attention. If engaging in Asia, recognize that clients might expect extensive in-person relationship building and be prepared to accommodate that with frequent visits. By augmenting their teams and processes in this way, EU deep-tech firms can offer the best of both worlds: the brilliance of European innovation and the customer-centric hustle that global markets demand.

The bottom line is that work habits and attitudes play a role in commercial success. Europe’s more balanced approach to work has many benefits – happier employees, less burnout, more diverse participation (for example, accommodating workers with families). But when it comes to startups trying to achieve product-market fit and scale, especially in competitive frontier fields, there is a need for urgency and hyper-service mentality at critical moments. European founders should consciously decide when to “shift to fifth gear” – during product launches, key client acquisitions, fundraising sprints – and ensure their team is prepared to go the extra mile at those times. By doing so, they can dispel the stereotype of being too slow or inflexible, without surrendering the core value of reasonable work-life balance in the long run.

From Grant-Funded Innovation to Market-Driven Growth

Another factor unique to Europe’s deep-tech landscape is the prevalence of grant-funded innovation and how that influences startup behavior. The EU and national governments have been very generous in funding R&D: programs like Horizon Europe, national research councils, and public-private initiatives pour billions into deep-tech (including fields like quantum, AI, biotech, etc.). This heavy public funding is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s been fantastic for advancing science – Europe “leads in scientific discovery” in many deep-tech domains and has nurtured thousands of high-tech projects via grants. On the other hand, reliance on grants can inadvertently shape an academic, non-commercial mindset among founders.

European deep-tech entrepreneurs often cut their teeth writing grant proposals rather than pitching to VCs or customers. This can be seen in their communication style: “Too often, European entrepreneurs approach fundraising like a grant proposal – precise, cautious, full of technical disclaimers – whereas their US counterparts project confidence and a bold narrative.” In academia and grant committees, the culture is to understate, hedge every claim, and focus on methodology. In business, especially in the startup arena, the culture rewards vision, speed, and conviction. The result is a storytelling gap: European deep-tech founders may pitch with meticulous detail and caveats (“nothing is ever 100% certain in science…”), which investors interpret as a lack of confidence or an excess of risk. Meanwhile, an American founder with half the tech maturity might thump their chest and say “our prototype works, and we’re ready to scale globally,” instilling greater confidence in backers.

Moreover, years of grant support can delay the urgency to achieve product-market fit. If a startup’s early funding comes from non-dilutive grants, they might spend those years focused on refining technology for grant milestones instead of testing market assumptions. When the grant money runs out, these companies sometimes find themselves ill-prepared to attract private investment or customers – the tech may be excellent, but they lack market traction, sales skills, or a scalable business model. As one EU deep-tech report bluntly put it, public grants have inadvertently “shaped founders into grant-focused entrepreneurs rather than investment-ready leaders,” emphasizing technical precision and risk avoidance over market potential. In effect, some teams remain in “research project” mode too long and struggle to flip to “growth company” mode when needed.

To overcome this, both the startups and the funding institutions are recognizing the need for change. Forward-looking programs now try to include commercialization training, incubators, and investor-readiness coaching alongside pure R&D funding. The European Innovation Council (EIC), for example, offers blended finance (grant + equity) and mandatory business mentorship to grant winners to push them toward market outcomes. Still, a 2022 analysis showed that of ~400 deep-tech spin-offs from research institutions in recent years, only 22% secured follow-on funding and even fewer reached scale. The pipeline is rich, but the conversion into viable businesses remains low.

For the founders themselves, the key is to pivot mindset as early as possible. Once the technology foundation is laid (often courtesy of grants), they must switch to a fully commercial regime. This means embracing sales and marketing, simplifying the product story for broader audiences, and focusing on customer needs rather than just cool science. It may also involve bringing in new team members with business expertise – e.g. a startup might hire a seasoned CEO or sales lead to complement a scientist-founder. European deep-tech companies that have succeeded globally (like Sweden’s Spotify or UK’s ARM in earlier eras) often did so by marrying technical brilliance with savvy go-to-market execution. As one commentary noted, innovation isn’t just about what you build – it’s about how you make the world believe in it.

Crucially, storytelling and leadership are now seen as core parts of deep-tech success, not optional soft skills. Investors fund people as much as technology; they need to believe the founding team can build a business, not just a product. European founders, especially those coming from academia, may need to consciously practice how to “own the room” in investor pitches and how to speak in terms of market impact and vision, not just technical metrics. This doesn’t mean exaggerating or losing scientific integrity – it means framing the technology in a bold, compelling narrative about how it will solve real problems or create huge value. For instance, instead of saying “our quantum device has 99.9% fidelity but still faces decoherence issues,” one might say “we have demonstrated a breakthrough approach in quantum computing that, with scaling, could outperform classical supercomputers on certain tasks – unlocking new possibilities in drug discovery and cryptography.” The latter paints a picture of potential and impact that resonates with investors and customers, even if under the hood there are challenges (which every deep-tech faces).

European policymakers and universities are also part of this puzzle. Tech transfer offices can help by refining their commercialization playbooks: simplify IP licensing, lower those initial equity grabs to leave more incentive for founders and investors, and provide seed funds for proof-of-concept that emphasize market validation. The EU is already moving in this direction with initiatives to fund “Deep Tech Valleys” and accelerators aimed at academic spin-offs, but execution varies by country. Some of the best practices are emerging from places like the UK’s Oxford/Cambridge ecosystem or Sweden’s “professor’s privilege” model (where academics own their IP, giving them freedom to commercialize). Aligning incentives so that researchers are encouraged – not penalized – for leaving the lab to start companies will help spur a more entrepreneurial culture.

In summary, Europe’s generous support for deep-tech R&D is a blessing that requires tweaks to translate into commercial wins. Startups must unlearn certain academic habits and adopt a startup mindset focused on speed, boldness, and customer engagement. As grant-funded teams transition to venture-funded companies, they need to shed the training wheels and ride at full commercial speed. The sooner European deep-tech innovators internalize this, the faster we will see “made in Europe” tech unicorns emerging from the laboratories.

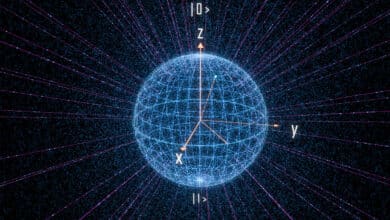

Quantum Technology: A Case Study of Europe’s Commercialization Challenge

To illustrate these dynamics, consider the field of quantum technology – often cited as a quintessential deep-tech sector. Europe has been at the forefront of quantum research for decades, boasting top scientific talent and many notable startups. In fact, nearly a quarter of the world’s quantum technology companies are based in Europe, and the EU trains more quantum PhDs and publishes more quantum research papers than any other region. Countries like Germany, France, the Netherlands, and the UK host cutting-edge quantum labs and ventures (e.g. IQM in Finland building quantum hardware, Pasqal in France working on quantum processors, multitudes of university spin-offs in sensing and cryptography). The EU has also committed massive public funding – over €11 billion since 2018 – through its Quantum Flagship and related programs to ensure Europe stays in the race.

Yet, when it comes to commercial outcomes, Europe’s quantum leadership is less apparent. The global quantum startup scene has seen U.S. companies sprint ahead in raising capital and hitting milestones. American firms like IonQ and Rigetti went public (via SPACs) early, raising substantial funds to build their quantum computers, and tech giants like IBM and Google have large quantum teams driving rapid progress. The U.S. approach couples significant private venture capital with government support, and a mentality of “move fast and get to market first.” Europe’s approach, by contrast, has been more about long-term public investment and a “sovereignty-first” strategy – aiming to build quantum capacity without relying on U.S. or Chinese tech giants. The ambition is high, but the risk is that strong public ambition collides with a weak private investment reality.

The numbers tell the story starkly: despite billions in EU public funding, Europe attracts just 5% of global private quantum investment, whereas the US draws about 50%. In the past year alone, U.S. private investment in quantum startups tripled, while European private investment fell by 40%. This has left European quantum ventures underfunded and potentially vulnerable. Many promising EU quantum startups raise initial seed rounds locally, but struggle to secure the mega-rounds needed for expensive hardware development or to scale commercial offerings. Often, they end up tapping U.S. or Asian investors (or even being acquired by non-European companies) to get the capital required.

Another challenge: commercial ecosystem and speed to market. Quantum technology is still nascent, but early applications (like quantum-safe encryption, quantum chemistry simulations, etc.) are being explored. The U.S. has a dynamic interplay of startups with big tech (Microsoft, Google, AWS all offer quantum cloud services) and even defense agencies (e.g. Pentagon funding quantum projects) that creates momentum to productize quantum research quickly. Europe, despite its talent, can be slower to spin up such public-private-commercial collaborations. For example, while European startups like Pasqal and Alice&Bob are making progress in quantum computing, and ORCA Computing in the UK is working on photonic quantum systems, their American peers often grab headlines for demonstrating quantum advantage or signing multi-million dollar deals with government and industry. The perception (and perhaps reality) is that the US quantum ecosystem is more agile and market-driven, while Europe’s is more academic and centrally planned.

That said, Europe is aware of this risk and is adjusting course. Just this year, the European Quantum Industry Consortium (QuIC) published a white paper urging urgent action to close the funding and commercialization gap, effectively saying Europe could lose its quantum edge without faster coordination and investment. The EU’s new Quantum Strategy, unveiled in 2023, includes measures to stimulate private co-investment (for example, a European Quantum Investment Fund is being set up) and support startups in scaling up production (such as funding pilot manufacturing lines for quantum chips). There’s also a push to develop a full “quantum stack” in Europe – ensuring that everything from the hardware to software and skills pipeline is grown domestically. This is crucial because many key components for quantum devices in Europe currently have to be imported, which is seen as a strategic vulnerability.

In the quantum field, we also see the cultural/work habit themes play out. Quantum startups often originate from university labs – say, a group of PhDs with a brilliant idea. They may benefit from substantial EU grants to build prototypes. But when it comes time to form a company and attract customers (like banks for quantum encryption, or pharma firms for quantum chemistry), those academic founders might lack experience in aggressive product development or enterprise sales. Anecdotally, some investors note that European quantum teams sometimes aim for perfection in the lab before engaging with the market, whereas an American startup might launch even if the hardware is rudimentary, just to start learning from customers and staking out market presence. The risk for Europe is that by the time its impeccably engineered solutions are ready, the market could already be dominated by first movers who iterated faster and built user ecosystems.

In summary, quantum technology exemplifies the broader deep-tech commercialization challenge: Europe has undeniable scientific prowess and even a head start in company formation, but it struggles to mobilize the same level of private capital and speed as the US (or even China, which has a state-driven but execution-focused model). To succeed in quantum, Europe will need to combine its public investments with a much stronger culture of entrepreneurship and commercialization – encouraging its quantum scientists to become quantum entrepreneurs who are not just inventors, but also deal-makers and builders of scalable businesses. Encouraging signs are emerging (for instance, several European quantum startups did raise €100M+ rounds in 2023-2024, some with participation of European funds), but there is a consensus that Europe must act with urgency so that it doesn’t miss out on the multi-billion-dollar industries that quantum and other deep technologies will create.

Bridging the Gap: Strategies for Europe’s Policymakers, Founders, and Universities

Closing Europe’s deep-tech commercialization gap will require coordinated effort from policymakers, startup founders, and university technology transfer offices alike. The challenges are clear, but so are the opportunities – Europe can build on its strengths (research excellence, top talent, supportive public policy) by addressing the weaknesses we’ve discussed. Here are a few strategies for each stakeholder group:

Policymakers & EU Institutions

Continue and expand initiatives that provide funding beyond the lab, such as the new EIC Scale-Up fund and national innovation banks, to address the late-stage funding gap. Policymakers should also work on reducing fragmentation – harmonizing regulations, creating true pan-European markets for new tech (for example, a single EU-wide sandbox for quantum or AI companies to operate under one set of rules).

Cutting bureaucratic red tape is critical: streamline standards and certifications across countries so startups don’t need to redo the process 27 times.

In addition, incentives can be tweaked to unleash more local capital – for instance, encouraging pension and insurance funds to allocate a higher percentage to venture capital and growth equity (perhaps through tax breaks or public co-investment programs).

Finally, celebrating success and tolerating failure should be part of policy messaging. Europe could benefit from campaigns that normalize entrepreneurial risk – e.g. showcasing successful founders who had failed ventures before, to chip away at the stigma of failure.

Startup Founders & Executives

Embrace a market-driven mindset from an early stage. Even if your deep-tech startup is born in a university, start engaging with real customers and industry partners as soon as possible – this will force you to refine the value proposition beyond the lab.

Invest in storytelling: craft a clear, compelling narrative of the problem you solve and why it matters, avoiding unnecessary technical jargon. Don’t hesitate to bring in business talent – a great CTO or scientist can benefit immensely from pairing with a CEO experienced in startups or a sharp VP of Sales who knows how to sell emerging technology.

Also, be strategic about your work culture as discussed: if you’re targeting global markets, build responsiveness and customer-centric practices into your company’s DNA. That might mean odd hours or travels for you as a founder – lead by example in showing your clients you’ll go the extra mile.

At the same time, differentiate your company by leveraging Europe’s strengths: for example, quality and reliability. Many customers will appreciate a team that is conscientious and methodical – as long as you also demonstrate agility when it counts.

In short, maintain your high standards but don’t let perfectionism or cautiousness become an excuse for inertia. Be bold in seeking feedback, iterating, and pushing towards commercialization milestones (like paid pilots, partnerships, and revenue) even if the tech isn’t 100% polished yet.

University TTOs and Research Institutions

Make your tech transfer processes faster and friendlier. This could include setting clear turnaround targets for licensing deals, offering standard term sheets that don’t overburden new spin-offs, and possibly adopting a more founder-friendly equity policy (for example, taking 5-10% ownership instead of 25%, or allowing dilution in follow-on rounds so external investors aren’t scared off). As noted, large initial equity stakes and prolonged negotiations are counterproductive – if a spin-off never gets off the ground commercially, a university’s 25% stake is worth zero. It’s better to have 5% of a future success than a quarter of nothing.

TTOs should also actively connect founders with mentors and investors – essentially acting as the catalyst to turn a scientist into an entrepreneur. Some European universities have started entrepreneur-in-residence programs and accelerator partnerships to support their spin-offs; these models should be expanded.

Additionally, consider cultural training: help academic founders understand the world of venture capital and startups, so they can transition mindsets. The goal for universities is to see their innovations make a real-world impact – that only happens if the spin-off companies thrive, which sometimes means letting go of control and trusting the founders and market to shape the journey.

Ultimately, Europe’s deep-tech commercialization issue is not due to lack of ingenuity – the ingenuity is there in spades. It’s about aligning ecosystem incentives and behaviors toward growth. By investing as much effort in business innovation as in technical innovation, Europe can unlock the full potential of its deep-tech sector. There are positive signs: Europe now produces more unicorns than ever, including in deep-tech fields, and success stories like battery champion Northvolt or AI unicorns like DeepL show that world-leading companies can spring from European soil. Policies are evolving too – for example, the new EU STEP program will put €1.4 billion into scaling up deep-tech in 2025, specifically to bridge funding gaps.

With the right adjustments, the next wave of deep-tech breakthroughs could see Europe not only inventing the future, but also bringing it to the world market on its own terms, turning its “deep-tech valley of death” into a peak of success.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.