Destructive Criticism – My experiences with negative feedback across cultures

Giving feedback is hard.

Giving good feedback is even harder.

Giving good feedback across cultures is next to impossible.

I learned this the hard way on my first project in Canada. After years of working in very direct-feedback cultures, I was thrown off by my Canadian boss’s gentler approach. In our first review meeting he “suggested that I think about” doing a task a different way. So I did exactly that – I thought about his suggestion, and ultimately decided not to change a thing.

A week later, the client gave their assessment of my deliverable. I was elated to hear that I had “some original ideas” and that the report was “relatively fine,” with just a note that perhaps I “should consider rewording parts of it.” I figured why fix what isn’t broken? My work was “fine” and even had “original” ideas, so I left it as-is.

Imagine my surprise when the client later complained that I had ignored their feedback and delivered a low-quality result. Soon after, I was called into a meeting with my boss and HR. I braced for a scolding. To my astonishment, the meeting was mostly praise for my work. Sure, in between all the compliments my boss did mention a “slight issue that I should address,” but I barely paid attention to that – I was buzzing from the glowing praise he was giving me. I walked out feeling overjoyed, convinced I was on track for great things in my career.

Only later did it dawn on me that I had, in fact, just received about the harshest negative feedback one can get in Canada. All those polite suggestions and mild words were the criticism – and I had completely misinterpreted them. What I heard as “relatively fine” and “consider maybe tweaking it” was meant as “nowhere near good enough – redo it!” In my boss’s eyes, he had practically yelled at me. But coming from my background, I missed the message entirely.

Why did I get it so wrong? To understand, you need to know where I came from.

The Direct Approach to Negative Feedback

Up until that Canadian project, I had spent my career in cultures that communicate feedback very directly. In places like Eastern Europe and Western Europe where I worked – from Slavic cultures to Dutch, German, even French – the norm was to be blunt and frank when delivering criticism. The philosophy was simple: don’t sugarcoat the message and risk confusion. As a result, the critical point of feedback was always front-loaded – often delivered immediately and without any small talk or cushioning language. A manager might start a conversation not with a polite greeting, but with something like, “Your deliverable sucks…” before even saying hello. The intention wasn’t to be rude; it was to ensure the message registers clearly and nothing gets lost in niceties. In these cultures, concern for the recipient’s feelings is secondary to getting the point across.

Direct-feedback communicators also tend to use what linguists call “upgraders” – words that intensify the criticism. You’ll hear phrases like “this is totally unacceptable,” “you absolutely missed the mark,” or “we definitely have a problem here.” These signal that the feedback is serious. By contrast, what I eventually learned is that my Canadian colleagues were using the opposite (more on that soon). But in my world back then, being straightforward was seen as being helpful and honest.

To give you an idea of just how stark direct feedback can be, consider how my old Dutch boss might have handled the scenario I faced in Canada. If he thought my report was poor, he would have said something like: “You have completely failed to meet our expectations. This report is an absolute mess. Rewrite it from scratch.” There would be no ambiguity about where I stood. Brutal? Maybe – but in that environment it was normal. In fact, hearing such blunt words was oddly reassuring: at least you knew exactly what the problem was and could fix it.

In the direct-feedback cultures I was used to, explicit praise was rare. It’s not that people never did good work; rather, managers saw positive feedback as almost unnecessary – if you weren’t hearing anything negative, that was the signal you were doing well. As the saying went, “no news is good news.” By contrast, negative feedback was frequent and expected. You’d hear promptly about every mistake or subpar effort, often with specific examples of what went wrong and how to improve. Some of my early bosses believed the fastest path to improvement was to find the flaws in everything. One joke was that in these environments people look for “the turd lining in every cloud,” not the silver lining. If something was 90% right, they’d zero in on the 10% that was wrong – not to tear you down, but to make sure you never stopped improving. It was tough love, delivered with a sledgehammer instead of a hug.

In “direct Negative feedback” cultures the most efficient path to continuous improvement is seeing the turd lining in every cloud

To make matters worse, most of my bosses and clients in my first years were active and retired military generals, intelligence officers, and police captains – those who, even in their direct-style cultures, would have been perceived as overly blunt, direct, and rude. If you have never had the pleasure of working with Croatian, Dutch, or German military officers, then you should know that their feedback giving is brutal. And constant. Cage-fighting pre-fight press conferences are romantic serenades in comparison. Brutally honest feedback is shared mercilessly by everyone. Colleagues who are not in your reporting line – and in no way involved or impacted by your project – would have no hesitation in telling you that your data center cage was a “cable salad” (a German idiom for a tangled mess) and that they felt fremdschämen, meaning they were embarrassed on my behalf, because my work quality was “beneath all pigs” (another colorful German phrase). Hyperbole aside, this was considered normal conversation on the job! Far from causing resentment, such blunt critiques were often seen as a kind of team-building exercise – a way to bond through mutual honesty and a shared commitment to high standards.

Surprisingly, nobody’s feelings were particularly hurt by this direct approach. I certainly didn’t take offense; it was what we expected. Honest, unvarnished feedback – even if unpleasant – was considered valuable. You knew it was aimed at the work, not at you personally, and that the critique was there to help you grow. In fact, receiving no criticism could be more worrisome (it might mean someone didn’t care enough to correct you and help you grow).

I even got to the point where I interpreted scant negative feedback as high praise. Once, I received the largest performance bonus of my life and a promotion right after a performance review meeting that lasted all of two minutes. In those two minutes, my manager told me that my habit of slouching at my desk looked unprofessional and that my accent could be “annoying” to clients. Then I was politely thanked for my work and sent on my way. That was it – meeting over. And you know what? I was thrilled. The fact that my boss could only come up with two minor complaints meant that everything else I was doing must have been outstanding. I literally walked on air the rest of that day, because in a culture where nitpicking is the norm, a short critique is the equivalent of a glowing review.

This direct style of negative feedback – call it “no sugar, all medicine” – can be incredibly effective within its own context. It drives constant improvement, leaves no ambiguity about performance, and treats adults like grown-ups who can handle tough truths. But as I discovered, trouble arises when a direct feedback person meets an indirect feedback culture (or vice versa). What is normal in one context can be utterly misinterpreted in another. Let’s look at that other side now.

The Indirect Approach to Negative Feedback

In contrast to the “say it as it is” philosophy, many cultures take a softer, more indirect approach to negative feedback. Here, the priority is to deliver the message politely and tactfully, so as to minimize hurt feelings or conflict. In these environments, being kind can be as important as being clear. Countries like Canada, the U.K., the U.S., and much of Asia often fall into this category (though there are nuances in each). If my Canadian colleagues were any indication, the rule was: criticize with care.

How do indirect-feedback cultures soften the blow? One common method is often jokingly called the “feedback sandwich” – start with a positive, then slip in the negative feedback, and follow up with another positive. For example: “Your work on this project is really great, I just have a few small suggestions for improvement, but overall keep up the good work!” The real message in the middle might be “you need to change X, Y, Z,” but it’s cushioned by praise on both sides. Canadians and Americans are particularly famous for this approach – so much so that in some circles it’s dubbed the “sh*t sandwich” (pardon the language) because the unpleasant part is hidden in between the warm fluffy parts. The idea is to make the criticism more palatable. And it does make sense: people in these cultures often believe that too direct a critique can demoralize the recipient or damage the relationship, so it’s better to wrap the negative in positives to show that your overall view of the person is still favorable.

Another strategy is the use of “downgraders” and “softeners” – gentle words or phrasing that dilute the sting of the feedback. Instead of saying “This report is unacceptable,” an indirect communicator might say, “Well, this report is kind of not what we expected” or “It’s a little bit off in some areas.” Qualifiers like “sort of,” “maybe,” “slightly” abound.

Likewise, direct orders or critiques get recast as polite questions or subtle hints. You’ll hear phrases such as, “Would you mind possibly doing X?“, “Perhaps we could try Y?“, or “I wonder if we should consider Z?“. The actual directive might be “Do X immediately,” but that sounds too harsh, so it’s softened to “Could you perhaps do X when you have a chance?” In the ears of someone from a direct culture, this can sound like a casual suggestion rather than an urgent request. And indeed, that’s exactly how I misread my boss’s “why don’t you think about doing it differently” remark – I took it as a polite, optional thought exercise, not a serious instruction.

Importantly, indirect negative feedback is almost always given in private. A boss from an indirect culture will typically pull you aside for a quiet word rather than call you out in front of your peers. Publicly shaming someone with criticism would be seen as unnecessarily cruel and embarrassing. This ties into the concept of “saving face,” which is especially prominent in many Asian cultures. Criticizing someone one-on-one or phrasing it gently allows the person to absorb the feedback without losing face in front of others. Even positive feedback might be given discreetly in some collective cultures, because single-ing someone out (even for praise) could make them uncomfortable. Compare that to Americans, who love being praised publicly – it just shows how differently recognition and criticism are handled across cultures.

The indirect approach certainly feels kinder and more diplomatic. During my years working in Asia and the Middle East – places known for very indirect communication – I observed that open confrontation or harsh criticism almost never happened. It was considered better to say nothing than to risk embarrassing someone. In fact, I remember going through an HR training in Singapore (a relatively indirect culture itself) where they flat-out told us that the worst way to deliver negative feedback is to use the sandwich method! The trainers argued that burying criticism between compliments was too confusing – by the time you got to the real point, the employee might only remember the “bread” (the praise) and miss the “meat” (the critique) entirely. Their preferred method was to give clear but polite feedback without dressing it up too much. This just goes to show: even among cultures that value indirectness, there are differing views on how indirect one should be. What some see as thoughtful and positive, others see as misleading.

In “Indirect Negative Feedback” cultures the path to continuous improvement is through seeing only the silver lining, ignoring clouds.

For the most part, though, indirect negative feedback cultures err on the side of positivity and preserving harmony. People focus on the silver linings and may even deliberately ignore the clouds. In these environments, if you point out too many flaws you risk being seen as overly critical or “not a team player.” The path to improvement is meant to be paved with encouragement and gentle nudges rather than hard criticism. I can personally see some benefits to this. In my experience, the indirect style helped reduce stress – people didn’t feel constantly under attack – and that did improve team morale and relationships. When everyone’s being very courteous, the workplace just feels nicer. On the flip side, as we’ve seen, the obvious risk is that the feedback may be so vague or sugar-coated that the core message doesn’t land. If the recipient doesn’t grasp that a criticism was made, nothing will change – and problems won’t get fixed.

So we have two dramatically different approaches: one says “tell it like it is, no matter what”, the other says “spare the feelings, wrap it softly.” Each works in its own context. The real challenge is what happens when these styles collide – as they inevitably do in today’s global workplaces.

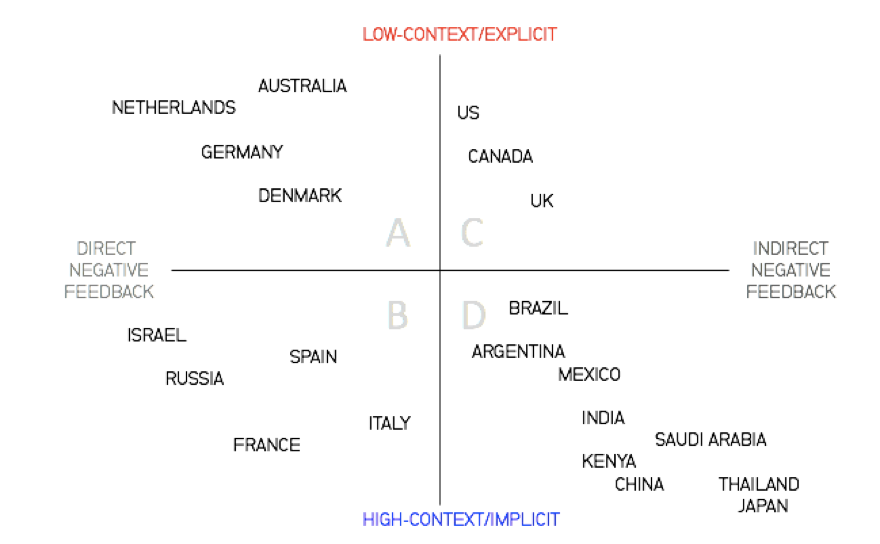

INSEAD professor Erin Meyer mapped some of these cultural differences in her book The Culture Map. She ranks high- and low-context cultures based on the directness of negative feedback.

Figure 1: Cultural tendencies in communication context and feedback styles, based on Erin Meyer’s research. Countries like the Netherlands and Germany fall on the “direct & explicit” end of negative feedback, while cultures such as Japan or Thailand exemplify the “indirect & high-context” extreme. Interestingly, some cultures (e.g. the USA, UK, Canada) are low-context in communication yet still tend toward polite or indirect criticism. Understanding where your team members come from on this spectrum can help in tailoring your feedback approach.

When Feedback Gets “Lost in Translation”

My Canadian feedback fiasco was a textbook case of cross-cultural miscommunication – but it’s far from an isolated incident. In fact, once I started sharing my story, I discovered many colleagues had similar tales of feedback gone wrong across cultures. For example, a German manager I met (working in London) told me about the first time his British boss “suggested” he do something differently. Just like me, he politely thanked his boss for the suggestion… and didn’t change a thing. To him, a suggestion was just that – optional input. Little did he know that in British business-speak, “I suggest you consider doing X” actually meant “Do X, ASAP, or there will be consequences.” He nearly got fired for insubordination, all because he took an indirect message at face value. Fortunately, he learned to decode those polite British phrases in time. *”Now I know that when my English colleagues say ‘maybe you could…’, what they often mean is ‘you really should…’,” he told me. He also realized that he needed to soften his own communication when giving feedback to his British team members, who found his German directness “rude and abrupt.” Misunderstandings like this can put any team on a rocky path if not addressed.

It goes both ways. I’ve heard Americans complain that their European coworkers seemed needlessly harsh or cold in delivering feedback: “It felt like a personal attack, they just listed everything wrong I did in front of the whole team!” an American might say. Meanwhile, the person from the direct culture is baffled: to them, being honest and specific is the respectful thing to do, and they meant the discussion to be about the work, not the person. On the flip side, I’ve seen colleagues from Europe scratch their heads at the indirect feedback style of North Americans. One Ukrainian teammate once pulled me aside after a meeting and asked, “Why do our Canadian colleagues always start with a bunch of compliments and then hide what they really want to say? It feels… dishonest.” He wasn’t accustomed to the “buffered” feedback style and wondered if the positives were even sincere. To him, the Canadian manager’s lengthy preamble of “we really value your work, you’ve been doing an excellent job” sounded like over-the-top flattery, when in fact it was a genuine attempt to soften the coming critique about a missed deadline.

The result of these style clashes? Confusion, frustration, and sometimes real damage to working relationships. The person giving feedback feels like they’ve communicated perfectly well – how could anyone miss the point or take offense at that? The person receiving it hears something entirely different from what was intended. In my case, I heard “great job overall” when my boss meant “this is unacceptable.” Other times it’s reversed – someone hears stinging criticism where none was intended. A well-meaning British manager might tell her French employee, “Your presentation was quite good.” She intends it as praise (in Britain “quite good” is positive, if a bit modest). But the French colleague is disheartened – in France, “quite good” said so lukewarmly would imply mediocrity at best. He’s used to more passionate critique (French feedback can be very direct on pointing out flaws, and genuine praise is given sparingly), so a tepid “quite good” feels like a let-down. Meanwhile, that same French manager might bluntly tell an American team member, “This report is totally unacceptable,” thinking clarity will be appreciated, but the American walks away feeling attacked and demoralized by the bluntness.

There’s even a famous tongue-in-cheek “Anglo-Dutch Translation Guide” that humorously lists phrases British people say, what others hear, and what Brits actually mean. For instance, if a British colleague says, “With all due respect…“, a Dutch person might interpret that as respect being given, but in reality the Brit is likely signaling strong disagreement (essentially “I think you’re wrong”). Or when a British or Canadian manager says, “Please consider doing XYZ,” they probably mean “Do XYZ” – not maybe, if you feel like it. In my own case, I eventually compiled a little “translation” cheat-sheet for Canadian English. For example, I learned that when a Canadian boss said “I’ll bear your feedback in mind,” it politely meant “I’m going to ignore your input”. If they said “It is fine,” it often meant “This is not good enough”, despite the reassuring wording. And if I heard “You have some original ideas,” I had to brace myself – that was basically code for “your ideas mostly suck”! These coded phrases were the only way I could make sense of the smiley, positive-sounding feedback I was getting while I kept missing promotions or getting pushback on my work.

To illustrate the indirect communication challenges, inspired by Nannette Ripmeester’s “Anglo-Dutch Translation Guide,” I created my own translation guide. It is only slightly exaggerated.

| When a Canadian boss says: | A Canadian boss means: | Marin used to hear: |

| I was a bit disappointed to hear… | I am very angry to hear… | They were a little bit disappointed to hear… |

| Please consider… | Do exactly as I say. | It’s on me to consider and decide. |

| I would suggest… | Do exactly as I say. | It’s on me to consider and decide. |

| It is fine. | It is not good enough. | It is fine. |

| There are a few minor issues you should address. | You are a lost cause. | All good, just a few minor issues I should address. |

| Perhaps you could give it some more thought. | This is terrible and you need to completely redo it. | This is good. Just refine it a bit. |

| With all due respect… | Your idea is stupid. | They think my work deserves respect. |

| I hear what you say. | I disagree completely. | They understand and agree with me. |

| I am sure that the issue was my fault. | It was your fault. | The boss is sure it is their fault. |

| I’ll bear your feedback in mind. | I won’t do anything about it. | They will keep it in mind and apply it the next time when applicable. |

| You’ll get there eventually. | You’ll never get there. | They think I am just about to achieve it. |

| This issue worries me slightly. | You are a lost cause. | There is a minor issue. |

| This is quite good. | This is a bit disappointing. | This is quite good. |

| I almost agree… | Hell will freeze over before I agree. | They almost agree. |

| You have some original ideas. | Your ideas suck. | I have some original ideas. |

| This is amazing / excellent / great | This is acceptable. | This is the best thing they ever saw. |

All of this might sound a bit comical, but in practice the stakes are high. When feedback gets lost in translation, performance suffers (because people don’t correct course) and working relationships strain or break (because one side thinks the other is rude, while the other side thinks their counterpart is dense or disingenuous). Small misunderstandings can spiral into big frustrations. A manager might start labeling a subordinate as “unresponsive” or “ineffective,” when in truth that employee just didn’t decode the indirect hints that were dropped. The subordinate, meanwhile, might see the manager as “unsupportive” or “two-faced,” not realizing that critical feedback was given – just in a subtle way. I’ve seen colleagues start to resent each other due to these misperceptions. The American thinks the Japanese employee agrees (because he didn’t openly disagree in the meeting), but in reality the Japanese employee had concerns that were never voiced – so the plan fails. Or a Scandinavian boss gives a frank critique meant to help, and his Middle Eastern team members take it as a humiliating public dressing-down – so they disengage. Without anyone meaning to, morale drops and trust erodes.

So what can we do about this? We’re not going to change our cultural upbringing overnight, and you shouldn’t have to walk on eggshells or read minds to work with colleagues from around the world. The good news is that with a bit of awareness and adaptation, we can bridge these gaps.

Bridging the Cultural Divide in Feedback

After decades of working across dozens of countries, I can say this: adapting your feedback style to different cultures is absolutely possible, but it takes conscious effort. Even with all my experience, I still find it challenging at times. The key is to acknowledge the differences openly and be willing to adjust your approach. Whether you’re a team leader or a team member, here are some strategies that have proven effective:

- Educate Yourself on Cultural Styles: Start by learning how your colleagues’ cultures tend to handle feedback. Are they generally more direct or indirect? Do they value subtlety or straight talk? Frameworks like Erin Meyer’s Culture Map are a great resource to understand where different countries fall on the spectrum. For example, knowing that the Dutch or Germans favor very direct critiques while Japanese or Middle Eastern cultures prize saving face can help set your expectations. Don’t stereotype or assume everyone from a culture is the same, but be aware of the tendencies. This awareness will help you calibrate your own style when working with them.

- Discuss the Difference Openly: It may feel awkward at first, but it’s hugely beneficial to have a conversation within your team about feedback preferences. Acknowledge that people have different styles. Something as simple as saying, “Hey, I know we all come from different backgrounds. How do you prefer to receive constructive criticism?” can go a long way. By getting it in the open, you take away the guesswork. Your team could even agree on some shared norms. For instance, indirect communicators might give direct colleagues permission to be more blunt with them, and direct communicators might agree not to be offended by a more roundabout approach. Creating this mutual understanding sets the stage for trust – everyone knows feedback is given with good intent, even if the style varies.

- Adapt How You Deliver Feedback: If you are from a direct-feedback culture dealing with more indirect colleagues, consider dialing it back a notch when you give criticism. You don’t need to abandon your honesty, but add a buffer or two so your feedback doesn’t come across as a personal attack. Make sure to explicitly mention something positive or appreciative before you deliver the critique – this isn’t “lying,” it’s showing that you recognize what’s going well even as you point out a problem. Try using a few qualifiers instead of absolute statements; for example, rather than “This code is completely wrong,” you could say “It looks like this code might not meet the requirements.” It may feel “soft” to you, but it helps the message get through to someone who isn’t used to bluntness. And remember to do it privately. Calling out mistakes in a group meeting can mortify an indirect-culture teammate and make them shut down. A one-on-one chat or even a written message might be better for delivering the critique, so they don’t lose face in front of others. Finally, be patient if your feedback isn’t immediately acted upon – it might be that they quietly acknowledged it but didn’t express that openly to you. Follow up gently to ensure the message was understood.

- Adapt How You Receive Feedback: If you’re the direct style person on the receiving end of indirect feedback, train yourself to listen between the lines. Don’t assume that all the praise means you have no areas to improve. If your manager or peer from a gentle-feedback culture is talking to you, ask yourself: “Are they hinting at something I should change?” If you’re unsure, ask clarifying questions in a polite way. For example, “Thanks for the feedback! Just to be clear, is there anything you’d like me to do differently on the next report?” This gives the person a chance to put any hidden critiques on the table. You might need to read tone and subtext more than you’re used to. Phrases like “maybe you could…” or “might be worth considering…” often imply a definite request or concern. It’s a bit of an art, but over time you’ll start catching the softer signals. Importantly, don’t take the politeness as insincerity – your indirect colleagues aren’t trying to mislead you; they truly believe this is the most respectful way to help you improve.

- For Indirect Communicators: Be More Explicit (When Needed): Maybe you’re on the other side – you come from a culture that values diplomacy, and now you’re working with straight-shooters who seem to expect everything spelled out plainly. First, understand that they won’t automatically pick up on subtle hints. If you tell your very direct German employee, “Perhaps you could arrive a bit earlier to meetings,” they might smile and say “sure,” and keep showing up late – because they didn’t realize you were actually unhappy with their tardiness. They would respond better to a more direct approach like, “You need to start arriving on time for meetings; it’s important.” That kind of phrasing might feel uncomfortably blunt to you, but to a direct-style person it sounds appropriately clear. Also, try to keep your feedback messages brief and focused when dealing with direct colleagues. If you lead in with too much small talk or excessive praise, they might find it confusing or even suspect you’re not being honest. It’s perfectly fine (and still polite) to say, “Overall good work, but the client is upset about X. Let’s fix that immediately.” They’ll appreciate you getting to the point. And don’t be alarmed if they give you tough feedback in return – remember, they likely intend it as helpful and respect you enough to be honest.

- Don’t Imitate – Communicate: If you’re an indirect communicator by nature, you might think you need to “get more tough” when working with a blunt culture. Conversely, if you’re naturally direct, you might try to flower up your language to fit into a very indirect environment. Some adjustment is good, but don’t overdo it or fake it unnaturally. As one expert notes, it’s possible to go too far and come off insincere or even offensive when you stray outside your cultural style. For example, a typically soft-spoken Korean manager tried to adopt the Dutch blunt style in a Dutch office – it backfired because he came across as angry, not assertive. The lesson: aim for a middle ground. Moderate your tone, but keep your authenticity. It’s better to communicate about the differences (“I’m not used to being so direct, but I’ll try to be clear – please bear with me”) rather than pretend to be something you’re not. Your colleagues will respect the effort and honesty more than a poor imitation of their style.

- Always Assume Good Intent: In cross-cultural situations, it’s easy to misread tone and intent. Until proven otherwise, assume your feedback-giver or receiver means well and is operating from their own cultural script, not trying to be difficult. If someone is brusque, don’t immediately conclude “they’re a jerk” – they might actually think they’re being efficient and helpful. If someone seems to dance around an issue, don’t assume they’re evasive or dishonest – they might believe they’re being tactful and respectful. Giving each other the benefit of the doubt creates psychological safety where you can then ask for clarification without anger. If something isn’t clear, say something. A simple, “I want to make sure I understand – are you saying …?” can clear up 90% of misunderstandings. Likewise, if you suspect your message wasn’t understood as intended, invite questions: “I realize I’m pretty direct; please feel free to ask if anything I said wasn’t clear or came off too strong.” This kind of openness goes a long way in preventing simmering resentments due to cultural misperceptions.

Above all, remember that negative feedback is meant to be constructive – it should be about improving the work, not tearing down the person. Culturally, we have different ways of driving that point home. But at the end of the day, whether you say it with a smile or say it with a stern face, the goal is the same: to help a colleague (or team) get better. If we keep that shared goal in mind, we can find a way to get the message across.

Navigating negative feedback across cultures will never be easy, but it doesn’t have to be “next to impossible” either. It’s a skill that can be learned, and it’s increasingly becoming a core competency for global leaders and teams. In my own journey, I’ve gone from being oblivious in Canada, to perhaps too blunt in the Middle East, to finding a happier medium (most days!) in diverse teams around the world. I continue to adapt and often still catch myself recalibrating my tone, adding a dash more diplomacy here, a spoonful more candor there, depending on whom I’m speaking with. It’s an ongoing learning process – but one that’s immensely rewarding. When done right, giving constructive criticism across cultures fosters growth, trust, and stronger performance for everyone involved. Teams actually become more cohesive when members feel they can understand each other and still speak honestly.

So the next time you have to tell a colleague something negative, take a moment to consider where they’re coming from. If you’re direct, maybe add a bit of cushion; if you’re indirect, maybe add a bit of clarity. If you’re not sure how they’ll take it, just ask. By making the implicit explicit, we turn “destructive criticism” into constructive dialogue. In a global workplace, that’s how we ensure feedback truly feeds improvement – across all cultures.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.