Quantum Utility Block: A Fast-Track, Modular Path to Quantum Utility

Table of Contents

19 Nov 2025 – Three quantum technology companies – QuantWare, Q-CTRL, and Qblox – jointly unveiled a new offering called the Quantum Utility Block (QUB), billing it as “the fastest path to quantum utility” for enterprises and research institutions. This announcement, made in Delft, Netherlands, signals a novel approach to deploying quantum computers: instead of relying on proprietary one-vendor systems or costly in-house development, organizations can now obtain a pre-validated, modular quantum computer architecture that is delivered as a full-stack package. The QUB comes in Small (5 qubits), Medium (17 qubits), and Large (41 qubits) configurations, and it integrates components from all three partners – QuantWare’s quantum processors, Qblox’s control electronics, and Q-CTRL’s software – into a turnkey system. The goal is to dramatically simplify on-premises quantum computing for those who want their own quantum hardware, offering “an accessible, cost-effective way to procure quantum systems” without the usual hassle.

A Modular Quantum Platform, Ready Out-of-the-Box

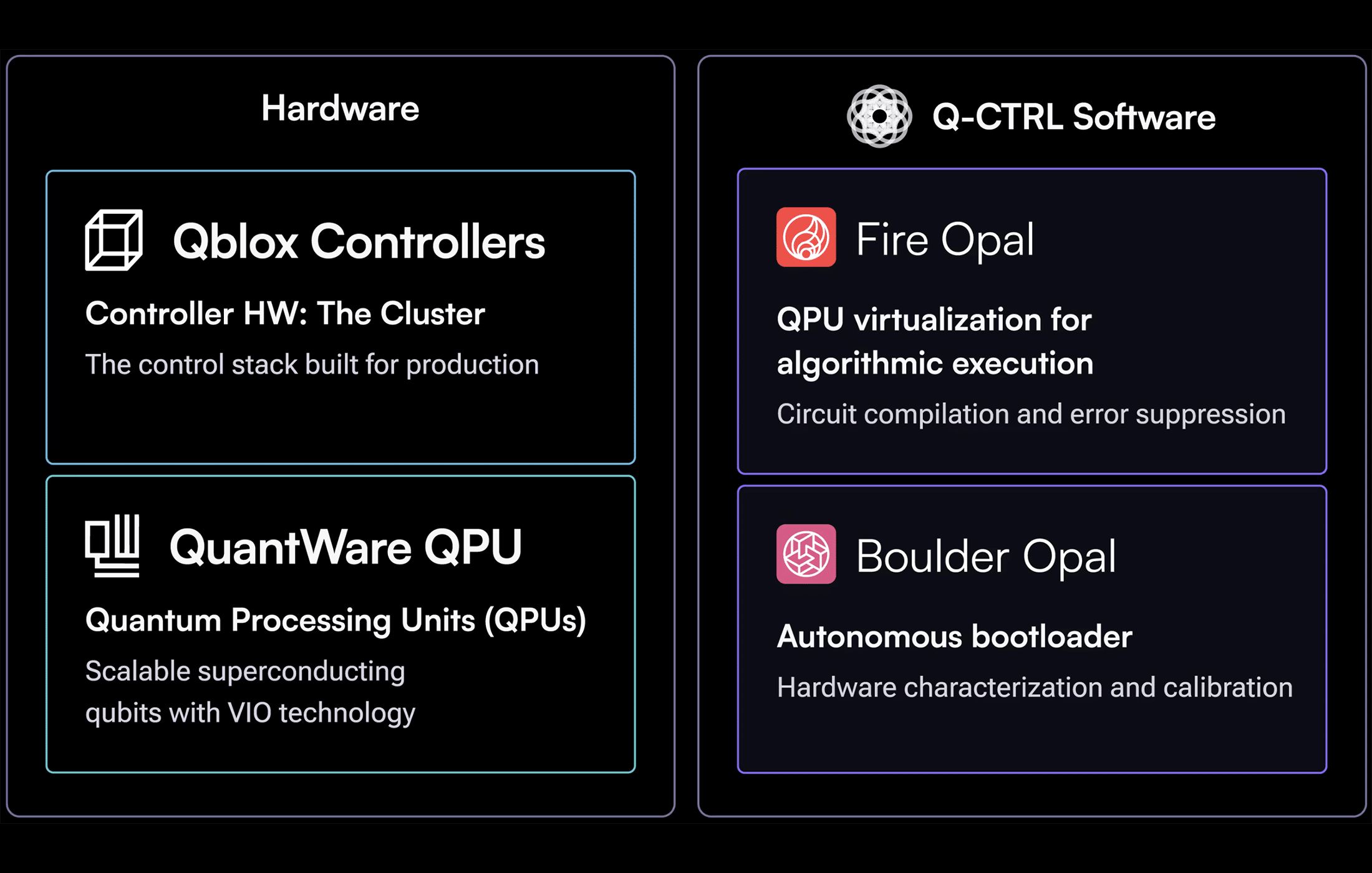

The Quantum Utility Block is essentially a reference architecture for a superconducting quantum computer that has been pre-validated and pre-integrated by the three specialist firms. In practical terms, this means an organization can order a QUB system and receive a fully assembled quantum machine with all the pieces working together – the qubit chip (from QuantWare), the control hardware (from Qblox), and the calibration and error suppression software (from Q-CTRL) – already tested as one unit.

According to the companies, these are the same components proven in real-world quantum operations at various labs, now packaged into a product for broader use. Crucially, the QUB’s design is modular and interoperable, giving buyers flexibility to upgrade or customize down the line. It’s a stark contrast to the status quo in early quantum adoption: “Until now, most organizations faced two extremes – closed full-stack systems that are inflexible and expensive, or do-it-yourself stacks that require enormous time, expertise, and resources”, as the press release notes. The QUB is intended to offer a third option – a middle ground that combines the power of a quantum computer with the transparency and flexibility of modular components.

One immediate benefit of this approach is speed. Normally, procuring or building a quantum computer can take years of planning, PhD-level expertise, and troubleshooting. With QUB, much of that complexity is handled by the creators upfront. The team claims that deployment timelines can shrink “from years to months” thanks to the pre-validated design. They also emphasize a reduced need for in-house quantum experts – Q-CTRL’s software (notably its Boulder Opal suite) provides autonomous calibration and performance management, meaning the system can tune itself and keep the qubits stable with minimal manual intervention. This kind of AI-assisted automation addresses a major pain point: there is a severe shortage of quantum hardware specialists, and smaller organizations struggle to recruit teams to babysit a fragile quantum processor. By embedding Q-CTRL’s machine learning-based control software, QUB “minimize[s] reliance on scarce quantum expertise”, essentially abstracting away some of the messy quantum tuning that typically goes on behind the scenes.

Cost is another factor. The partnership estimates that the total cost of ownership for a QUB could be up to ten times lower than a comparable bespoke solution. This comes partly from the modular design – you’re not paying one big vendor’s premium for a black-box system, and you can upgrade components over time instead of replacing the whole machine. It’s also due to unified support: the three companies jointly support the product, so an enterprise isn’t left coordinating between multiple vendors if something goes wrong. In effect, QUB aims to de-risk the decision of “when and how to begin [the] quantum journey” for companies that have been sitting on the fence. As QuantWare CEO Matthijs (Matt) Rijlaarsdam put it, “organizations no longer need to choose between opaque closed-stack systems or risky do-it-yourself builds. QUB lets them deploy proven quantum architectures faster, at lower cost, and with complete control over their technology future.” The promise is bold: a circuit-ready quantum computer delivered to your facility, ready to run quantum algorithms out-of-the-box with much less fuss than assembling one from scratch.

Technically, the QUB leverages superconducting transmon qubits, the same qubit technology used by IBM and Google in their quantum processors. QuantWare specializes in making these qubit chips; in fact, it is known as the world’s highest-volume supplier of quantum processing units, offering devices like a 5-qubit chip (for the Small QUB) up through a 41-qubit chip (for the Large QUB). Qblox provides the “quantum control stack” – essentially the electronic nerve center that sends microwave pulses to control the qubits and reads out their states. Qblox’s control hardware (Cluster modules and related electronics) has a reputation for scalability and precision, having been used by many labs worldwide. On the software side, Q-CTRL contributes its Fire Opal and Boulder Opal tools – Fire Opal suppresses errors in the algorithms by optimizing how quantum operations are executed, while Boulder Opal automates the calibration and tuning of the qubits and hardware. These tools are integrated such that the QUB can self-calibrate and mitigate noise autonomously, which is critical for maintaining performance as the machine scales.

To illustrate the user experience: an enterprise or research lab could install a QUB (say, the Medium 17-qubit model) in their facility – which, yes, means they’d need a cryogenic refrigerator and supporting infrastructure – and from day one, the system would come with “circuit-ready” qubits that have been tuned and error-corrected by Q-CTRL’s software. The organization could then start running quantum algorithms (for example, via Q-CTRL’s interface or their own software stack if they prefer) without first spending months wrestling with qubit calibration. It brings quantum hardware closer to a plug-and-play paradigm than we’ve seen so far. As Alex Shih, Q-CTRL’s VP of Product, said, the partnership “is about making full-scale quantum computing systems useful, accessible, and economically viable for the broadest range of users” – showing a “clear and scalable path to quantum utility built on openness, collaboration, and practical tools”.

Fast-Tracking the Road to “Quantum Utility”

It’s worth unpacking the term “quantum utility”, which the companies highlight. We’ve heard of quantum supremacy (a quantum computer decisively beating a classical one on some task) and quantum advantage (a quantum computer showing a useful edge on a practical problem), but quantum utility is being used here in a slightly different sense. It implies delivering useful outcomes on real problems, reliably and regularly, via quantum computing – essentially the point at which quantum technology becomes a valuable tool for industry or science, not just a lab experiment or a one-off stunt. The QUB is explicitly framed as a fast track to that stage: by lowering procurement and operational barriers, it hopes to enable more institutions to actually use quantum computers for meaningful tasks. Fields like drug discovery, financial modeling, materials science, optimization, and logistics are cited as targets where quantum computing could eventually “transform industries”. The idea is that if companies can get their hands on a quantum machine sooner (even a modestly sized one) and integrate it with their existing data centers or HPC workflows, they can start developing quantum solutions now – building expertise and IP in anticipation of future more powerful processors.

One concrete step in this direction is the planned QUB demonstration in Colorado. Alongside the QUB launch, the partners announced a collaboration with a U.S. organization called Elevate Quantum (a tech hub) to install a QUB system at Elevate’s facility in Colorado as a testbed called Q-PAC (Quantum Platform for the Advancement of Commercialization). Slated for 2026, Q-PAC will be the first Quantum Open Architecture system deployed in the United States, serving as a “hands-on” quantum computing sandbox for companies, researchers, and students. Importantly, Q-PAC is described as providing Quantum-as-a-Service cloud access in addition to on-premise use. In other words, once the QUB is up and running in Colorado, remote users will be able to access it over the cloud, much like they do with IBM or AWS Braket, except this machine is built on an open, modular stack. From a strategic perspective, Q-PAC aims to “strengthen U.S. leadership in quantum system integration and workforce development” by giving a broad base of users access to a state-of-the-art but openness-focused quantum system. It’s essentially a showcase of the QUB’s capabilities and an opportunity to demonstrate how such modular systems can slot into existing tech environments (like data centers and HPC facilities).

For the QUB partners, Q-PAC will also be a high-profile proof-of-concept to attract future customers. If global researchers can experiment on the QUB in Colorado and validate its performance, it lowers the perceived risk for others considering buying one. The messaging is very much “look, this works – come try it.” Jessi Olsen, COO of Elevate Quantum, highlighted that this open collaboration “lowers barriers, reduces risk, and unlocks immediate, real-world access to quantum capabilities – while also creating a national resource for training the next generation of quantum talent.” Training quantum talent is a big angle here: having more physical quantum machines in the field (not just at IBM or Google) means more engineers and students can learn by doing, which is crucial for growing the ecosystem. It’s analogous to the spread of supercomputers or laboratories – the more accessible they are, the more expertise gets built. In fact, the open-access philosophy of QUB reminds me of the early days of classical computing, when the industry shifted from a few big closed mainframes to many interactive, standardized systems that universities and companies could actually own and operate. We may be seeing a similar shift in quantum, from the “cloud only” model (where a handful of providers host quantum processors that everyone leases time on) towards a more distributed model where many organizations can possess their own quantum hardware, tailored to their needs. This doesn’t mean every company will buy a quantum computer – far from it – but for those who have the resources and desire, QUB-like solutions make it much more feasible to join the club of quantum operators.

Embracing Quantum Open Architecture (QOA)

At the heart of QUB’s philosophy is the concept of Quantum Open Architecture (QOA) – a term that captures the modular, multi-vendor approach to building quantum systems. This approach is a departure from the closed, monolithic stacks offered by some big quantum players. In a traditional model, if you wanted a quantum computer, you might have to buy the whole thing from one company (or rely on their cloud), with little ability to mix and match components. QOA flips that script: it encourages assembling quantum computers from specialized components provided by different suppliers, much as one might build a classical computing system by sourcing CPUs, GPUs, storage, etc., from various makers. This “open architecture model” is transformative because it “enables institutions to assemble world-class quantum computers using specialized components from multiple suppliers”, rather than being locked into a single vendor’s ecosystem.

The QUB is a flagship example of QOA in action. Each partner focuses on what it does best – QuantWare on the quantum chip, Qblox on control hardware, Q-CTRL on software – and the end result is a “best-of-breed” composite system. We’ve already seen signs of this open approach yielding results. In Italy, for instance, researchers at the University of Naples recently assembled the country’s largest quantum computer (a 64-qubit machine) by combining components from different open-architecture vendors. They used QuantWare’s 64-qubit Tenor QPU as the centerpiece and integrated it with other subsystems to create a full working machine. That project, completed in 2025, was a proof-point that open quantum architecture can drastically reduce the time and cost to build a cutting-edge system – the Tenor-based computer was deployed much faster and more affordably than if the university had to, say, develop its own 64-qubit chip or buy an entire closed system from a big company. It also demonstrated another advantage: the Naples team gained deep understanding of each component by assembling it themselves, which aided in troubleshooting and customization. In other words, QOA not only decentralizes innovation but also democratizes knowledge. Instead of a black-box quantum appliance, an open system is more transparent – researchers and engineers can tinker with the control electronics, adjust the software, even swap out the quantum processor in the future. This is very much in line with academic and enterprise needs, where being able to optimize and tailor a system is valuable (and also an educational boon for students learning the hardware).

By launching QUB, QuantWare, Q-CTRL, and Qblox are doubling down on the QOA ethos. Niels Bultink, CEO of Qblox, emphasized that “QUB brings together three complementary leaders to make quantum systems more open, accessible and practical than ever before. This collaboration enables a scalable path to quantum utility.” Openness here doesn’t mean everything is open-source (these are still proprietary products coming together), but it means open interfaces and interoperability – the parts can talk to each other through standard or well-documented interfaces, and a customer isn’t locked out from modifying their setup. In fact, the QUB offering even allows for customization options – qualified partners can, for example, engage the team for integration into a specific data center environment or for algorithm development consulting. This shows a degree of flexibility and service-minded approach that’s often lacking in one-size-fits-all products.

From my perspective, the rise of Quantum Open Architecture is a healthy development for the industry. It fosters a vibrant ecosystem of specialized quantum companies that can collaborate rather than compete head-on. Each can innovate in their niche – whether it’s making better qubit chips, or better control systems, or better software – and their innovations can combine to push the overall capability forward. Matt Rijlaarsdam of QuantWare has spoken about empowering the whole ecosystem through QOA, rather than trying to do everything under one roof. This modular ecosystem approach mirrors what happened in classical computing: no single company builds every part of a supercomputer anymore, and that competition and specialization have driven rapid advances. We might see a similar acceleration in quantum tech as the open approach gains traction.

There’s also a geopolitical and strategic angle to this. Notably, QuantWare and Qblox are European (both based in the Netherlands), Q-CTRL originated in Australia – none are the typical US tech giants. Europe in particular has been advocating for open, collaborative models in quantum development as a way to catch up and carve out a niche. The European quantum community often talks about “technological sovereignty” and “strategic autonomy” in quantum (more on that shortly), and one pillar of that is having an open framework where domestic players can contribute components to larger projects. Europe doesn’t yet have an IBM-scale quantum provider; instead, it has dozens of smaller startups and scale-ups each tackling pieces of the puzzle. Embracing QOA allows these companies to team up and deliver full solutions that compete with the big boys. In fact, the European Quantum Strategy explicitly includes initiatives like Open Quantum Testbeds and competence centers to encourage exactly this kind of cross-organization collaboration. QUB can be seen as a direct product of that philosophy – a few European and allied startups banding together to create something bigger than the sum of their parts, without needing a single dominant player. It’s a path to innovation through coalition, which might be Europe’s best bet to stay in the quantum race given the fragmented nature of its industry. And importantly, because QUB is an on-premises solution, a customer in Europe (or anywhere) can physically have the machine on their soil, under their full control – an appealing prospect for those worried about dependency on foreign cloud services.

Quantum Sovereignty and My Take on What’s Next

The term “quantum sovereignty” has been gaining currency recently, and it ties in closely with efforts like QUB. At its core, quantum sovereignty means a nation (or region) achieving the ability to develop and control quantum technologies domestically, without undue reliance on foreign providers. In practice, that implies being able to build a full quantum tech stack – from the chips and cryogenics to the software and algorithms – within one’s own borders or trusted network. It’s an extremely ambitious goal (perhaps only China and the U.S. might eventually come close, and even they collaborate internationally to some extent), but it has become a strategic priority in Europe and elsewhere. The rationale is straightforward: quantum computers could unlock transformative capabilities (and even threaten cryptographic security), so no country wants to be entirely at the mercy of another’s technology when that revolution hits. We’ve seen how dependence on foreign tech (say, for semiconductors or cloud computing) can become a strategic vulnerability, and policymakers are keen not to repeat that with quantum.

In my view, the QUB initiative contributes to quantum sovereignty in a meaningful way. For one, it broadens the supplier base for quantum systems. Instead of one or two large companies controlling all high-end quantum deployments, we now have a viable system coming from a coalition of smaller companies. This introduces redundancy and resilience in the supply chain – an enterprise or government could choose a QUB over a perhaps U.S.-based closed solution, which diversifies who they depend on. It’s still not complete independence (for example, the QUB uses superconducting qubits which require dilution refrigerators – a market dominated by a few firms like Bluefors in Finland; also, Q-CTRL’s software, while Australian, runs on classical hardware that likely comes from global vendors, etc.). But it’s a step toward a world where no single nation or vendor holds all the keys. Europe has articulated a goal of achieving “full-stack quantum sovereignty,” covering the entire value chain from materials to software. Initiatives like QUB align with that by ensuring European companies are in the mix at every layer (QuantWare for chips, Qblox for control hardware, etc.). Moreover, by being open and modular, QUB could integrate with other European innovations – for instance, if a new European cryogenic technology or a home-grown quantum networking interface emerges, it could potentially plug into the QUB architecture. This adaptability is important for future-proofing Europe’s quantum infrastructure.

Another aspect is talent and knowledge sovereignty. When institutions host and operate their own quantum computers (versus just accessing black boxes over the cloud), they develop internal expertise and intellectual property. The University of Naples example showed that by building their machine, they trained students and researchers in every aspect of the system. If Europe (and other regions) multiply such efforts – through testbeds, QUB deployments, etc. – they will cultivate a generation of engineers who know how to run and innovate on quantum hardware. That human capital is arguably as important as the hardware itself in the long run. It’s something the EU is focusing on in its strategies (the Quantum Skills agenda). I personally think having widely distributed quantum systems (even if they are small-scale initially) is going to accelerate progress far more than a few big machines in isolated corporate labs. It’s analogous to how the spread of personal computers and open systems in the 1980s led to a boom in software developers and ingenuity, compared to the era of one mainframe per city.

Of course, we should be realistic: a 41-qubit quantum computer (the largest QUB model right now) is not going to outperform supercomputers on problems of global importance. We’re still in the era of noisy, intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. So when we talk about “quantum utility,” it’s with an eye to the future. These machines will likely be used for research, education, and developing quantum algorithms in-house, rather than immediately cracking big commercial use-cases. However, achieving “utility” is also about integration and workflow. A 17-qubit machine that’s well-integrated into your data center, where your classical HPC jobs can offload certain subroutines to the quantum chip automatically, might start to deliver hybrid benefits – for example, by speeding up a specific simulation or optimization by a small factor using a variational quantum algorithm. Over time, those small advantages could compound, especially as the hardware scales to, say, 50, then 100, then 1000 qubits with error mitigation. QUB’s design is explicitly meant to be scalable: the partners talk about an “upgrade path towards thousands of qubits” and even mention that their technology choices (like QuantWare’s 3D chip architecture VIO) are aiming at “MegaQubit-scale” systems in the long term. The modular approach means a future QUB might simply involve more qubit modules or higher-density chips plus more Qblox controllers in a larger rack. In fact, Qblox has been working on a next-gen control system with cryogenic integration and NVIDIA backends for scalability, and QuantWare announced a 10,000-qubit chip blueprint (the VIO-40K) around the same time – all signs that the pieces for much bigger machines will come, and when they do, a QUB-like architecture could incorporate them without a complete redesign.

From a personal perspective, I find the narrative here quite exciting: it’s a story of modularity and openness triumphing in a field often seen as esoteric and inaccessible. There’s a parallel to be drawn with the early computer industry or even the space industry: what was once the domain of government-like giants is being democratized by nimble collaborations and standardization. We often talk about “quantum advantage”, but an unsung milestone is when quantum computing becomes mundane enough that a corporation’s IT department can purchase a system and treat it (almost) like any other specialized hardware. The QUB isn’t quite at the “plug in and forget” level – quantum computers will still be finicky – but it’s a big step closer to normalizing the idea of local quantum infrastructure. And for those of us in regions that are not home to the tech super-giants, that normalization is key to participating in the revolution on equal footing.

Looking ahead, I will be watching how the Quantum Utility Block is received. Will research labs and companies line up to get their own 5- or 17-qubit machines? The first deployments (outside of the Elevate Colorado testbed) will tell us about demand. It may be that only well-funded labs and nation-scale projects (like national quantum centers) buy these initially. But if they show clear value – like dramatically faster experimentation cycles, or the ability to develop proprietary quantum algorithms in-house securely – then wider adoption could follow. I suspect other vendors will respond as well. For instance, we might see similar “full-stack in a box” solutions from other consortia of hardware and software vendors, perhaps targeting different qubit technologies (ion traps, photonics, etc.) or different scales. This could spark a healthy competition in the quantum integrator space.

In sum, the launch of the QUB feels like a milestone in the maturation of the quantum computing industry. It underscores a shift from pure R&D and isolated cloud access to a more distributed, collaborative model of growth. By combining Quantum Open Architecture principles with a focus on practical deployment, QUB touches on both the technological and policy ambitions of the quantum community – speeding up utility and fostering sovereignty. It’s a development that shows how much the landscape has evolved even in the past couple of years. As someone who closely follows quantum tech, I find this trend toward openness and modularity not only technically sensible but philosophically refreshing. Quantum computing, after all, was born from global scientific collaboration; keeping it from devolving into a monopolistic or regionally siloed arena will ensure we all get to benefit from – and contribute to – the quantum future.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.