Quantum Key Distribution (QKD): Why Countries Differ on Its Future

Table of Contents

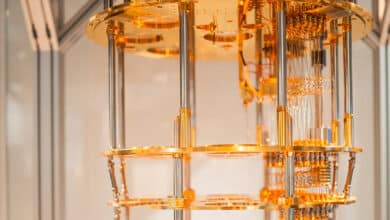

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) – a method of securing communications using quantum physics – has become a flashpoint of debate worldwide. Recent news (like Google’s announcement favoring post-quantum algorithms over QKD) highlights how divided opinions are. Some nations are investing heavily in QKD networks as the next frontier of secure communications, while others remain skeptical and prioritize post-quantum cryptography (PQC).

United States and Allies: Emphasizing PQC Over QKD

In the U.S. and allies like the UK the official stance has been to downplay QKD and focus on PQC. U.S. security agencies argue that QKD is impractical for most real-world uses and that robust cryptographic algorithms (PQC) are a better solution. The U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) explicitly “does not support the usage of QKD” for protecting national security communications. Instead, NSA and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have put their weight behind standardizing PQC algorithms that can run on today’s classical networks. This approach treats the quantum threat as something to be solved with new math (PQC) rather than new physics.

The rationale behind the U.S. skepticism is rooted in QKD’s practical limitations. Key reasons cited by these agencies for sidelining QKD include:

- It’s an incomplete solution: QKD only generates encryption keys and still requires classical cryptography for authentication, so you’d need post-quantum algorithms anyway to verify who you’re talking to. In other words, QKD can’t replace public-key crypto entirely because it provides no built-in identity authentication.

- Special hardware and infrastructure: Unlike PQC algorithms that run on existing hardware, QKD demands dedicated fiber lines or line-of-sight links and quantum hardware (single-photon detectors, etc.) It “cannot be implemented in software or as a service on a network” and doesn’t integrate easily into today’s equipment. This makes it costly and logistically complex to deploy widely.

- Distance and trust issues: QKD links have limited range (tens of kilometers on fiber before repeaters) and often require “trusted nodes” to extend farther. Each intermediate node must be secure, introducing new insider threat risks and infrastructure cost. An eavesdropper can also simply block the quantum signal (causing a denial-of-service) even if they can’t crack it, which is a concern for high-assurance systems.

It’s no surprise, then, that U.S. officials see QKD as a niche at best. The NSA concluded that quantum-resistant encryption is “more cost effective and easily maintained” than QKD, and stated it does “not anticipate certifying or approving any QKD” products for national security use unless its limitations are overcome.

In the same vein, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) took a public stance in 2025 that mirrors the NSA’s view. The NCSC “will not support the use of QKD for government or military applications”, endorsing PQC as the primary defense against future quantum attacks. For civilian sectors, British authorities warn that QKD should never be solely relied on and must be paired with strong classical authentication if used at all.

This U.S./UK position represents the “QKD skeptic” camp: they acknowledge the theoretical security of QKD’s quantum physics, but see its real-world drawbacks as too severe. The preference is to put resources into upgrading our encryption algorithms (a global PQC rollout is already underway) rather than building new quantum communication infrastructure. From my vantage point, this caution is understandable – these agencies are responsible for securing vast existing networks, so a software-based fix has huge appeal.

However, not everyone in the world shares this dismissive view of QKD, as we’ll see next.

Europe: Cautious Agencies but Strategic Investments in QKD

Europe’s relationship with QKD is more complicated. On one hand, many European cybersecurity authorities agree with the Americans about QKD’s shortcomings. In early 2024, a coalition of agencies from France (ANSSI), Germany (BSI), the Netherlands, and Sweden published a joint “position paper” outlining the uses and limits of QKD. Their assessment was clear that today’s QKD requires specialized infrastructure, suffers functional limitations, and is only applicable in certain niche use cases. They noted QKD is “not yet sufficiently mature from a security perspective” and urged decision-makers to prioritize post-quantum cryptography for broad quantum-safe migration. In other words, Europe’s technical experts see QKD as an intriguing technology that still needs time to ripen.

Yet, at the same time, Europe as a whole is actively investing in QKD deployment as a strategic asset. The European Union has launched an ambitious initiative to build an integrated European Quantum Communication Infrastructure (EuroQCI) spanning all member states. This project will combine terrestrial fiber QKD links with satellites to create a continent-wide secure network. The goal is to protect critical infrastructure and government communications by leveraging QKD’s unique ability to detect interception attempts. All 27 EU countries have backed EuroQCI, underscoring a political will in Europe to be at the forefront of quantum-secure networks by 2030. In fact, the European Space Agency and European Commission just formalized plans for a satellite constellation (Eagle-1 launching 2026) dedicated to QKD, as part of this initiative.

How do we reconcile these two threads in Europe? It appears Europe is hedging its bets. While national cyber agencies caution against premature reliance on QKD, the EU leadership doesn’t want to fall behind in case QKD becomes essential. Europe has a history of nurturing strategic tech capabilities internally – and quantum communications are seen as one such strategic frontier. There are also several European companies and research groups that are pioneers in QKD (e.g. Switzerland’s ID Quantique, Toshiba’s Cambridge research lab), and they’ve demonstrated metropolitan QKD networks and testbeds over the years. European researchers have achieved high secret key rates (millions of bits per second) on shorter fiber networks, and even multi-user entanglement-based networks in test environments. These successes keep interest in QKD alive on the continent.

In summary, Europe’s stance might be characterized as “cautiously pro-QKD.” The technical experts urge: “don’t ignore PQC, and don’t believe hype,” but the strategic planners say: “we should develop QKD capability just in case and to learn its potential.”

As a European (and someone deeply involved in quantum-safe tech), I actually find this dual approach wise – it mirrors the idea of defense in depth. You shore up classical cryptography (with PQC) and explore quantum communications for the future, rather than putting all eggs in one basket.

China and Asia: Full Steam Ahead on QKD

If the West is lukewarm about QKD, China is absolutely bullish. China has made QKD a centerpiece of its national science and technology strategy over the past decade. As early as 2016, China launched the world’s first quantum satellite (“Micius”) and demonstrated QKD links from space to ground across 2,600 km. By 2017, they completed a 2,000 km Beijing-Shanghai fiber QKD backbone connecting major cities. Chinese scientists then went on to integrate satellite and fiber links into the world’s first nationwide quantum communication network, spanning a total distance of 4,600 km and serving users across the country. Crucially, this network isn’t just a lab demo – it connected over 150 real-world users (banks, electric grid control centers, government sites) via QKD-protected links. To me, that’s a staggering level of deployment compared to anywhere else in the world.

Chinese officials and researchers speak of QKD in terms of strategic necessity. They tout that quantum communication is “unhackable” and see it as the “future of secure information transfer for banks, power grids and other sectors”. Prof. Pan Jianwei – a lead scientist behind China’s quantum network – stated that their work shows “quantum communication technology is sufficiently mature for large-scale practical applications.” This optimism is backed by steady improvements: China has achieved satellite QKD key rates forty times higher than a few years ago by improving technology, and extended fiber QKD distances beyond 500 km using new protocols like twin-field QKD. They are now working on smaller, more cost-efficient QKD satellites and high-altitude platforms to enable global coverage, aiming to have a worldwide quantum communications network by around 2030 (a goal frequently mentioned in China’s quantum roadmap).

China’s strong endorsement has also influenced its neighbors. Japan has been researching QKD for years (a Tokyo QKD network testbed was built as far back as 2010), and Japanese firms like Toshiba have been leaders in QKD device development. Singapore built a island-wide quantum network test platform connecting universities and government labs, as part of its quantum tech program. South Korea and India have launched their own QKD experiments (India, for example, demonstrated QKD between cities in 2021 and is supporting startups in this field). Even smaller states like Singapore, Italy, and Austria have all hosted multi-node QKD trial networks to develop know-how.

The overall picture in Asia is that QKD is taken very seriously as a coming technology – one that could confer strategic advantages. In particular, China’s head start has created a bandwagon effect and perhaps a sense of urgency. We see talk of international quantum secure communication alliances; for instance, there have been discussions of China linking its QKD network with partners in Russia and other BRICS countries to create a secure communications zone insulated from Western eavesdropping. While such geopolitical implications are beyond the scope of this article, it’s clear that in the East, QKD is not viewed as a quirky experiment but as a critical, inevitable part of future infrastructure.

As someone observing this from a Western perspective, I find the contrast striking. In Beijing, QKD is almost a patriotic science achievement – they’re proving technological leadership. In Washington, QKD is often portrayed as a boondoggle. The truth may lie somewhere in between, but China’s progress shows that many of the supposed “impossibilities” around QKD (like scaling to a large network) can be overcome with enough investment and ingenuity.

Standardization and Industry: Bridging the Divide

Apart from national security policies, there’s another important layer to this story: global standard-setting and industry consortia. While governments argue the merits of QKD, international standards bodies have been busy laying the groundwork to make QKD practical and interoperable. For example, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) has had an Industry Specification Group on QKD since 2008, involving experts from academia, industry, and government worldwide. The ETSI QKD group has developed a suite of specifications – from interface standards to security proofs – to ensure that different QKD systems can work together securely. In 2023, ETSI even released the world’s first Protection Profile for QKD devices, essentially a security certification framework to validate QKD equipment against common criteria. This kind of work is crucial if QKD is ever to move beyond proprietary links and become a broadly adopted technology.

It’s notable that participants from North America, Europe, and Asia all take part in these standardization efforts, even if their governments’ enthusiasm levels differ. Companies like Toshiba, ID Quantique, and telecom operators have a vested interest in shaping QKD standards. There are also collaborative projects – the ITU (International Telecommunication Union) and other bodies have working groups on quantum communications. If QKD is to truly go global, it will require common protocols (for example, how to handle key management, how to authenticate QKD nodes, etc.). The work happening in these committees might not grab headlines, but it’s steadily addressing many of the technical challenges that critics often cite.

From what I’ve seen, one major concern – interoperability between different vendors’ QKD systems – is being addressed through these evolving standards. The fact that ETSI’s group includes members from across continents suggests a recognition: if QKD is coming, we need to ensure it’s not fragmented or insecurely implemented. In a sense, the standard-setting community is keeping the door open for QKD, even as some national policymakers remain unconvinced.

My Perspective – QKD Deserves a Seat at the Table

I will admit my bias: I believe QKD, in the long run, should be part of the cybersecurity equation. No, QKD is not a silver bullet to the quantum threat – it won’t magically solve all our encryption woes, and it’s certainly not ready to replace classical cryptography today. But I worry that outright dismissing QKD (as some Western positions do) could be shortsighted. If quantum-safe security is our goal, shouldn’t we pursue multiple complementary approaches? PQC is absolutely essential, but adding QKD on top in certain scenarios could provide extra security layers (and potentially new capabilities like intrusion detection via quantum channels).

Many of the technical challenges that made QKD seem impractical are actively being solved by researchers. There is a regular drumbeat of progress in the quantum communications field that doesn’t always make mainstream news.

For example, one long-standing limitation of satellite QKD is that it typically only works at night – daylight sky noise blinds the quantum signals. Well, just last year, a team at Heriot-Watt University proposed a clever way to beat this “daylight noise” problem, using a new encoding and filtering technique to allow quantum links even at dawn and dusk. Their simulations show that by switching the photon encoding scheme (using time and phase encoding), they can filter out much of the sunlight interference, potentially enabling round-the-clock QKD via satellite in the near future. This kind of innovation extends the viable hours of satellite QKD by several hours a day – a significant step toward 24/7 global quantum networks. It’s a reminder that what’s true of QKD technology today (e.g. “it only works at night”) might not remain true tomorrow.

Similarly, distance barriers are falling. New protocols like twin-field QKD and quantum repeaters in development promise to push QKD over hundreds or even thousands of kilometers without trusted intermediaries. In the UK, we recently saw a 410 km QKD network demonstration linking Cambridge and Bristol, achieving the country’s first quantum-secured video call and data transmission over standard fiber infrastructure. Impressively, that network simultaneously ran different QKD schemes (both QKD with “particles of light” and distributed entanglement) over the same backbone. A few years ago, critics would have said such integration and distance were unthinkable for QKD – yet here it was, achieved in a multi-city trial. Every few months, another research paper comes out chipping away at what used to be QKD’s limitations (higher key rates, better single-photon detectors, quantum memory for repeaters, you name it).

My view is that we should invest in QKD R&D now so that we aren’t caught flat-footed later. Even if PQC covers 95% of use cases, there may remain critical applications where the unique properties of QKD provide benefits – think ultra-sensitive diplomatic communications, inter-datacenter links for banks, or securing the control channels of critical infrastructure. QKD’s ability to physically detect eavesdropping is something classical cryptography cannot do; that could become very valuable in certain threat scenarios. Also, as quantum networks evolve (eventually leading to a quantum internet of interconnected quantum computers), QKD might move from a niche to a necessity for linking quantum devices.

Of course, I’m not advocating blind hype. The skepticism from national security experts has its place: it keeps QKD vendors honest about security claims and highlights where more work is needed. It’s true that QKD doesn’t address data integrity or authentication by itself, and we must keep those points in mind. But to me, the sensible path is the dual approach: deploy PQC (because it’s our best bet against quantum code-breaking), and continue polishing QKD so that it becomes more practical and interoperable. This way, if large-scale quantum computers do arrive, we have both belt and suspenders for our security – cryptographic algorithms robust against quantum attacks, and quantum communication channels that add an extra layer of defense.

In conclusion, the global divide on QKD comes down to differing philosophies: “better safe than sorry” vs. “show me it works at scale.” The U.S. and its allies are in the latter camp for now, while China and others are forging ahead in the former. As an advocate for robust quantum-safe security, I think a blend of these philosophies is healthiest. Let’s be hard-nosed about QKD’s challenges (yes, there are many), but let’s also keep pushing the boundaries of what QKD can do. The quantum threat to encryption is multifaceted, and our response can be too.

Quantum Upside & Quantum Risk - Handled

My company - Applied Quantum - helps governments, enterprises, and investors prepare for both the upside and the risk of quantum technologies. We deliver concise board and investor briefings; demystify quantum computing, sensing, and communications; craft national and corporate strategies to capture advantage; and turn plans into delivery. We help you mitigate the quantum risk by executing crypto‑inventory, crypto‑agility implementation, PQC migration, and broader defenses against the quantum threat. We run vendor due diligence, proof‑of‑value pilots, standards and policy alignment, workforce training, and procurement support, then oversee implementation across your organization. Contact me if you want help.